Antiheroes vs. Anti-Hero

Harmony Korine and Taylor Swift. Plus the premiere of Spigot radio with Paul Pfeiffer!

To dispel any confusion: Paul Pfeiffer is not a cornball.

The time has come: Spigot migrates into audio this Wednesday, April 24, at 6 pm on Montez Press Radio. I’ll be joined by two brilliant guests: Paul Pfeiffer, who has a superb retrospective at LA MoCA up through June 16, and Paige K. B., who’ll be cross-examining the new Taylor Swift record. We’ll also be doing some live on-air wine tasting. Tune in! If you have my number, call or text while we’re on and I’ll try to work your queries or comments into the broadcast.

Film

Harmony Korine is a genius of capturing precisely how stupid and lurid America is, which is why the LA premiere for his new movie, Aggro Dr1ft, took place at a strip club. New York being thoroughly sanitized by Wegmans-shopping condo dwellers at this point, our local launch was staged at Elsewhere, a concert/dance venue that was described to me as “kind of lame” by those who should know. Indeed, it felt a little corporate, tidy and trained, overpoliced—a funny contrast to the film, which is, in predictably, about fucked-up people living in a shadow world beyond the margins of polite society.

Aggro Dr1ft has been frequently maligned since it premiered last fall at festivals in Venice, Toronto, and New York; here’s a fun example, “‘Aggro Dr1ft’ Is One of the Stupidest Films Ever,” from some Lord of the Rings fan with a blog that hasn’t been redesigned since 2006. More estimable critics, however, have more or less agreed.

This critic does not. Aggro Dr1ft is totally sick, which I mean as high compliment and with the purest double entendre.

Foremost, the movie looks amazing. Aggro Dr1ft was apparently shot with infrared cameras, but it was also heavily postproduced into variegated washes of acid yellow, terminator-eye red, neon blue and green. The results are gloriously scorching depictions of Florida landscapes, tactically clad musclemen, hot cars, and hypersexualized women. It’s the visual equivalent of standing in front of the speakers at Merzbow show—which is something I like, whatever that says about me. Hollywood blockbusters spend fifty or a hundred times as much on their visual effects to produce muddy, corny CGI wire-fighting and incoherent gushes of sterile superpowers. Korine’s low-budget, jacked-in, jacked-up style feels both fresh and strangely naturalistic.

This perverse “naturalism” has nothing to do with verisimilitude or a lifelike plot— Aggro Dr1ft is the story of the world’s greatest assassin, named Bo, hired to do one more big job. It’s a deliberate cliché, which is part of why the movie feels real to the collective imagination. Korine calls its aesthetic, something he’s building out through his new creative outfit EDGLRD, “gamecore.” And indeed, the movie plays like a series of cut scenes, with ancillary characters moving in static repetitive ways and lots of voiceover. Even at moments of conversation, it’s more like characters are conducting simultaneous internal monologues rather than talking to each other. I’m not even sure the actors’ lips move. This strategy, plus the druggy palette and occasional eruptions of monstrous visions, perfectly evokes the sense that we’re all dreamwalking through life with one leg in virtual space and the other in our fantasies, irrevocably cut off from everyone around us.

Despite its seeming milieu, Aggro Dr1ft has no pretense to sociology, like those annoying Sean Baker flicks. It’s pitched to appear like the crazed deprived interior life of a citizen manqué brainwashed with a sluice of Jordan Peterson-esque bootstrap rhetoric, self-pitying self-help, and American exceptionalism; who like Aggro’s murderous protagonist repeats to themselves, “I am the hero. I am the hero.” The fabric of the public sphere is visionary violence, and occasionally American dreams come true. The recurring appearance of horned demons in the film accompanies the protagonist’s desire for transfiguration, something almost technopagan if you get your spirituality from a bong load laced with DMT.

The rudimentary plot is not quite enough to get through the run time of 80 minutes, but almost. One drug lord wants to kill another drug lord, or something like that, and Bo takes the gig. The hokeyness of the construct is as much to the point as the cinema-pilled gangster delusions of Jean-Paul Belmondo’s character in Godard’s Breathless. In the end Bo kills the creep who hires him, for no particularly clear reason, and moves on to the big bad, who takes the form of a piggish winged demon with a harem of enslaved strippers and escorted by cloaked dwarves. While Bo is a loving family man, it turns out he’s also just a guy who loves killing, and telling himself he’s doing the world some good via the slaughter.

In the last several months, audiences been served up a spate of auteurish contract killer movies. Fincher’s The Killer, with its moody Smiths soundtrack, came out last fall; at the same festivals where Aggro Dr1ft premiered, so too did Michael Keaton’s Knox Goes Away (killer with encroaching dementia) and Richard Linklater’s Hit Man (fake assassin gets caught up in real murder). Keaton’s flick was released some weeks ago, with Hit Man getting its theatrical run, like Aggro Dr1ft, in May.

Why hit men? Maybe people just love lies. Maybe it’s because they feel like they’re living lies themselves, or they’re thrilled by the possibility that you could plausibly manipulate reality so easily and glide through a double life. The true world by contrast feels intractable, as if nothing in it can ever change—capitalist realism, if I may toss Mark Fischer into Korine-land. Like a contract killer, people feel terminally alone. And like the archetypal gangster, they want to leave their jobs but never quite can. An overpoliced world generates fantasies of running wild, of lawlessness, of a Darwinian life of fighting and fucking, one that falls back on atavistic gender roles and Neanderthal states of mind.

Given the bleak, vaguely suicidal setup, the sense of foreboding attached to the existential musings of our “hero,” and the deluded quality of everyone in the film, I had assumed Bo would meet a grim and brutal end when he confronts the diabolical devil/gangster. In fact, quite to the contrary. Him emerging victorious in a fight with the sword-wielding giant using what looks like a penknife ends up being the perfect ending, perfectly impossible—the dumb happy denouement we require. Bo frees the slave girls, liberates the creep’s diminutive praetorian guard. Turns out he really is A+ at his job.

Music

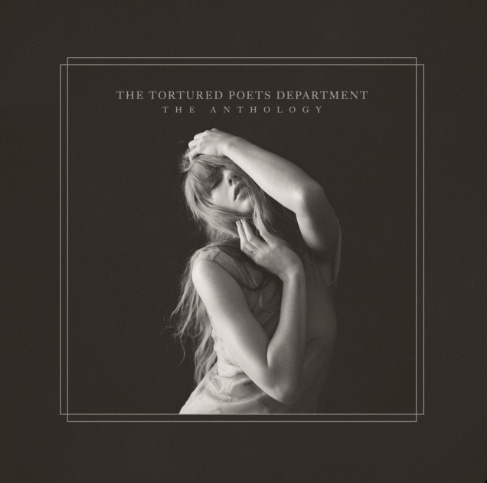

Taylor Swift ruined my weekend. The 2 am revelation that her new album was a double dip felt sadistic, even though it was just as likely a fiscal maneuver as it was artistic hubris. To get through it all I had to start rubbing cocaine on my gums, somewhere between “I Can Fix Him (No I Really Can)” and “loml.”

In the end, if you cut out two thirds of The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology’s thirty-odd songs, you’d have a better record than Midnights. “So Long, London” is effective. “Clara Bow”: crisp and wry. It also sounds atypically like a real song, structured, whereas a lot of the record sounds like slurry. More than anything Swift needs new producers. We’ve all heard enough of Jack Antonoff’s Drive-soundtrack-ripoff synths. She also needs to put down the thesaurus. The record is unbearably prolix from jump; its second couplet rhymes alcoholic and aesthetic.

If you’re patient, the Anthology section also has music worth settling into. “Chloe or Sam or Sophia or Marcus,” to paraphrase its refrain, breaks my cold, cold heart. “The Black Dog” is a classic Swift track, detailed yet easy to identify with—who among us hasn’t “accidentally” stalked our exes? And “So High School” is good pop fun, the clearest braiding together of her old themes and her new real-life nerd-jock romance. People quailing over the Aristotle line, or “Touch me while your bros play Grand Theft Auto,” have no sense of humor. I also credit the author with enough self-awareness for the references to Dylan Thomas, Patti Smith, and the Chelsea Hotel to be a mockery of the title track’s protagonists, just like the idiot boyfriend’s typewriter, rather than reflections of any personal bad taste.

But to me there’s only one song worthy of extended reflection on The Tortured Poets Department: the unhinged chef d’oeuvre “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?”

A fundamental fissure in Swift’s output is between perfectionism and self-exposure. How much of yourself are you truly revealing if you’re always in total control, always making yourself—like Aggro Dr1ft’s assassin—the hero? Not much, I’d say. This apparent contradiction doesn’t bother me, however, in part because I try not to think about the songs as “revealing” some authentic Taylor behind them.

But “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” is something new, a song polished to high sheen that presents a persona at odds with her meticulously sympathetic good-girl character. Here she’s an unalloyed monster, which makes the track unique, a horror movie in a universe of rom-coms and tearjerkers.

The delivery of the song’s opening lines mirrors that of Taylor’s #1 girl-crush Lana at the beginning of the old fave “Blue Jeans.” But the narrative is none of Lana’s swoon, just pure embitterment. Before we’ve hit the first chorus, Swift declares that she feeds off hate: “If you wanted me dead, you should've just said / Nothing makes me feel more alive.”

This may of course sound familiar to students of Reputation. The verses of “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” recount various ways in which the protagonist has been mistreated and maligned. She’s been tormented and wronged. But for once her viciousness makes her a less than totally empathetic victim, driven mad but gone too far—Jokerfied! The song presents a real antihero, not the clumsy, innocuous figure of Midnights’ best bop. Wielding a favorite trope in a disconcertingly jaunty chorus, she becomes a gleeful terror, a witch swooping into a cocktail party. Her unexpected riposte to the rhetorical “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” is “You should be.” And she’s not kidding.

“Who’s Afraid” contains the most violent image in Swift’s canon. Imagining herself as a caged beast—imprisoned by the media, the “circus” of her life as a celebrity, yes yes—she quotes the ringmaster: “Don’t you worry, folks / We took out all her teeth.” This line gives me chills, though I suppose your response may depend on how often you yourself have dental nightmares. The maestro of bridges uses that sacrosanct section of her songwriting here to articulate nutjob-level megalomania and paranoia: “They tell me everything is not about me / But what if it is?”

I’ve always wondered what would it be like if Swift one day just snapped, preferably in a fashion that was confined to songwriting. “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” is that song. It’s spine-tingling to hear her inhabit a fiendish character unleavened by jokes or propriety, to show her range—which the rest of TPPD sadly does not do. It’s the only song where she’s ever made herself truly unlikable. It’s a jolt that points a way out of the musical impasse she seems to have reached.

I firmly disagree with your take on Wegmans