Basic Bitch Edition, Part 2

Wolfgang meets Taylor, plus Hand Habits and a Midnights wine pairing

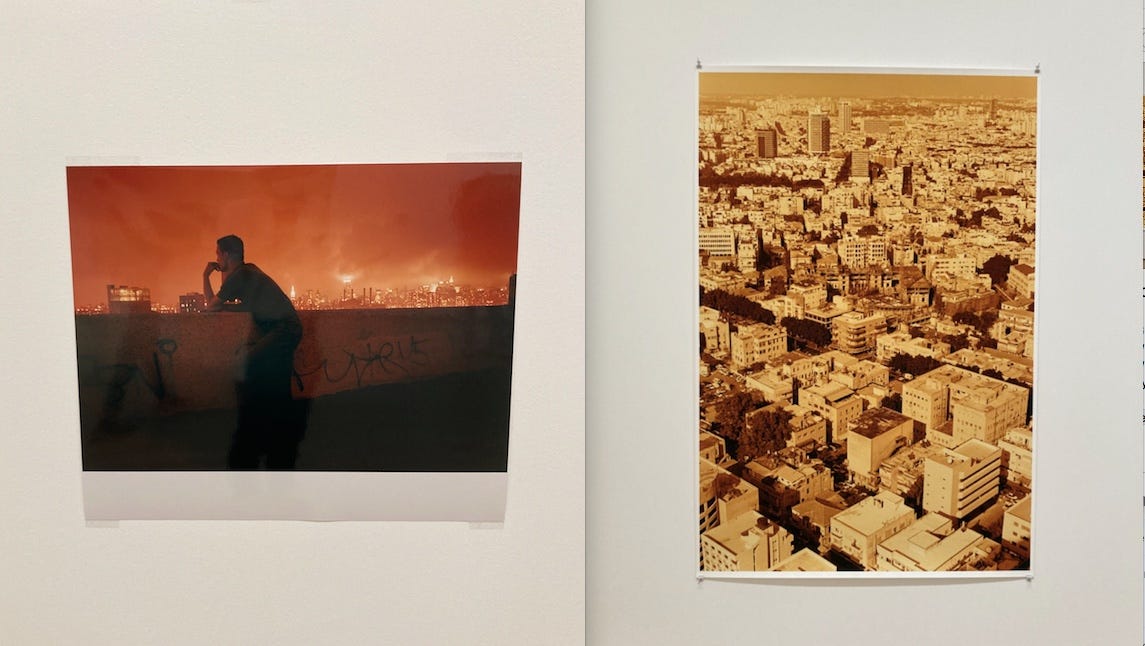

Though it might seem strange, dear reader, Taylor Swift and Wolfgang Tillmans are both basic bitches. I say this with all love and admiration: both TS and Wolfgang have become so important in their fields as to become baseline, fundamental, the ground rather than the figure, and thus paradoxically hard to see. They achieve this in different ways, Swift by saturating all media, Tillmans by distilling what the experience of visual saturation is like. When you exit Tillmans’s show at MoMA there’s even a nod to the dispersion of self this status brings about, a hall-of-mirrors sculpture made with Isa Genzken that plunges you into a mise en abyme.

Back near the beginning of the exhibition, in gallery 3, observing the crowd, I found myself thinking about a different kind of dissolution of the self: the show seemed like a great show to place get laid. There were a lot of people young and old, but younger than usual for MoMA, paired and solo and in little packs, chatting intimately, all in a very good mood. And why shouldn’t they be? There was lots of sexy youth on display in the work, seeded with enough death to qualify as sophisticated and enough technical medium-reflexivity to qualify as intellectual. A perfect date show, thus. Afterward you could talk about politics, or you could talk about the negatives you burned in the darkroom you worked in during college, or you could talk about celebrities and models, or you could talk about the other kind of stars, the ones in the sky, or you could talk about technology, or you could talk about travel, or you could talk about an elusive existential quality, of being somehow alone no matter how much in the middle of things you are. With all that to work with, surely you can overcome your millennial bed death.

It’s the erotics of being networked, with everything everywhere all at once giving you a tingle instead of neural collapse. This orientation, like much about Tillmans, feels very ’90s. I imprison him within this decade a little cavalierly, yes, and perhaps without due weighting of his later work. But in a way it’s his own fault for becoming too famous then, for his work becoming too iconic—and not merely within the marbled atria of art. The 1990s were the last time anyone really gave a shit about print magazines, the last time they seemed cutting edge within broader culture, and Tillmans embodied it while also remaining somewhat absent. He might have been his subjects, Lutz and Alex or that kid pissing on the office chair or the rat in the sewer grate or the queen Kate Moss herself.

The networking association is encouraged by the way MoMA has chosen to present his work. The install juxtaposes sizes and scales and framed works with those merely taped to the wall and (to a degree) chronology. I loved it; anything formal would have killed the whole project, so props to Roxana Marcoci and the artist himself. You can imagine him wandering around the galleries afterhours, moving things around by trial and error until a certain balance of the schematic and improvisational was achieved. The array of works palpitates with perfectly irregular repetitions: portraits, the night sky, technology, abstraction, current events and newspaper clippings. My favorite set of works are the windowsills, seemingly shot over the years in Tillmans’s studio, where various small items rest. The images remind you of the outside world, that which is uncapturable. Perhaps this is what he’s going for: a kind of sublime created not by seeing something but by seeing everything—and of course it remains just out of reach, no matter whether you look in the squat or the photo lab. Very German romantic, in its way.

The title, To Look Without Fear, reminds me of two things: Nauman’s iconic Run from Fear, Fun from Rear (1972)—not inapposite for the crown prince of Berghain—and a slightly corny but also great quote from Tillmans’s countryman Werner Herzog: “The poet must not avert his eyes.” (I can’t find the original source for that one; Werner just seems to trot out a variation on it every once in a while.) Tillmans’s title is practically a riff on Herzog’s line, and it locates him, like Herzog in his weird way, in the tradition of German objectivist impulses in art, from August Sander’s 1929, Nazi-suppressed Face of Our Time and the Neue Sachlichkeit to the Bechers and the Düsseldorf School. Looming between these two historically is an even more compendious MoMA show, the 1955 exhibition The Family of Man, curated by Edward Steichen (a reference deftly noted by David Rimanelli). The same impulse that guided that show, to document the wondrous variety of human beings who share this planet, feels very much in tune with Tillmans’s project over the years. He’s a humanist lib, as his EU campaign made clear. In a way, Tillmans’s work is very simple, untroubled by the ways photography has processed the various paroxysms of twentieth-century art, with which the medium for so long grappled as it contended to be considered an art form while also developing its own internal logics and styles.

If Tillmans is simple, of course, it does not mean that he isn’t kind of great. The Concorde pictures: simple, great. The Freischwimmer abstractions, made in a darkroom and looking like nothing so much as dye in water: simple, beguiling. Walking through the show, it’s hard not to be stunned by how easily he seems to be able to make any kind of picture look good, and for how long he’s been doing it. (Hoops fans may analogize him as more Lebron James than Michael Jordan.) Even the seemingly banal and discomposed still lifes drain you into them, and the photos with bold subject matter—AA Breakfast, for example—aren’t sensationalized. I’m not sure how he does it, but he certainly does do it. His snapshotty look has become definitive, so much so that, to me, it’s impossible to say what a Tillmans photo looks like. Perhaps because of this, the images don’t feel dated. He defined the vernacular or, alternately, anticipated the aesethicization and volume that civilians would be able to approach in photography thanks to the smartphone, the app, the filter. Which is why so many people were walking through the show with a grin on their face: they see themselves in the work.

Wine

El Coto Rosado 2020 Rioja. What would would-be lovers sip at the bar in the Modern after departing To Look Without Fear? A glass of natural wine, probably orange. Midnights, on the other hand, is a merlot kind of record, silky and easy. But for this basic bitch finale I could only hark back to Taylor’s shoutout on “Maroon” to cheap-ass screwtop rosé. Fortunately among the cheapest available at my outstanding local booze outlet, Queens Liquor, is a Rioja with 10% of garnacha thrown in. Thus it was dark and relatively husky, including in the vegetal sense, with a little watermelon, a little cherry, and just enough of that particular tang that reminds you there’s something industrially produced about it. Since it was a screwtop I cracked it while on my evening constitutional, and guess what? It tasted great at room temperature. El Coto is pretty, dark in color, almost amber in the light of an incandescent bulb, though not much aroma. But what do you expect for $11, except to be left wondering one fuzzy morning, with someone’s feet in your lap, asking how you got there, anyway?

Music

Even the most devoted of us tires of Taylor Swift sometimes. Thus: Hand Habits. I discovered them on October 21, the day after the Midnights release, as part of my mainlining Twitter that day. In the midst of debates over Taylor’s pitch-shifted vocals, I came across this amazing statement of intent:

Now that is a band I would pay to see at the Meadowlands. Thus I set aside my sour delectation of Jack Antonoff’s production style for a palate wash: Fun House. Hand Habits’ most recent album lines up with their own aspirational description, minus some Burial here and some Moritz there. (Next time!) The record blends basement pop and folk country-rock—it’s a Saddle Creek release, and the band’s protagonist, Meg Duffy, plays guitar for Perfume Genius, if that gives you a picture.

The vocals lead the proceedings, criss-crossing the same plaintive-ethereal register as Neil Young, the guitar even venturing into Rust Never Sleeps territory at times, e.g. “Concrete & Feathers.” Duffy is also, I would guess, a fan of Elliot Smith, though sounding more resilient than broken, with Smith’s Figure 8-era Beatlesque sound spirit-guiding tracks like “No Difference.” The record has a very every-day-it’s-raining vibe, shuffling brushed drums and occasional vocal harmonies, resulting in some really beautiful bits.