Down with Transparency

Amina Ross at Someday. Plus Thanksgiving wine experiments, a Spigot zine, and another art-institution meltdown

Do you like things to make sense? Me neither! I like to be bemused; it’s the first step toward intrigue.

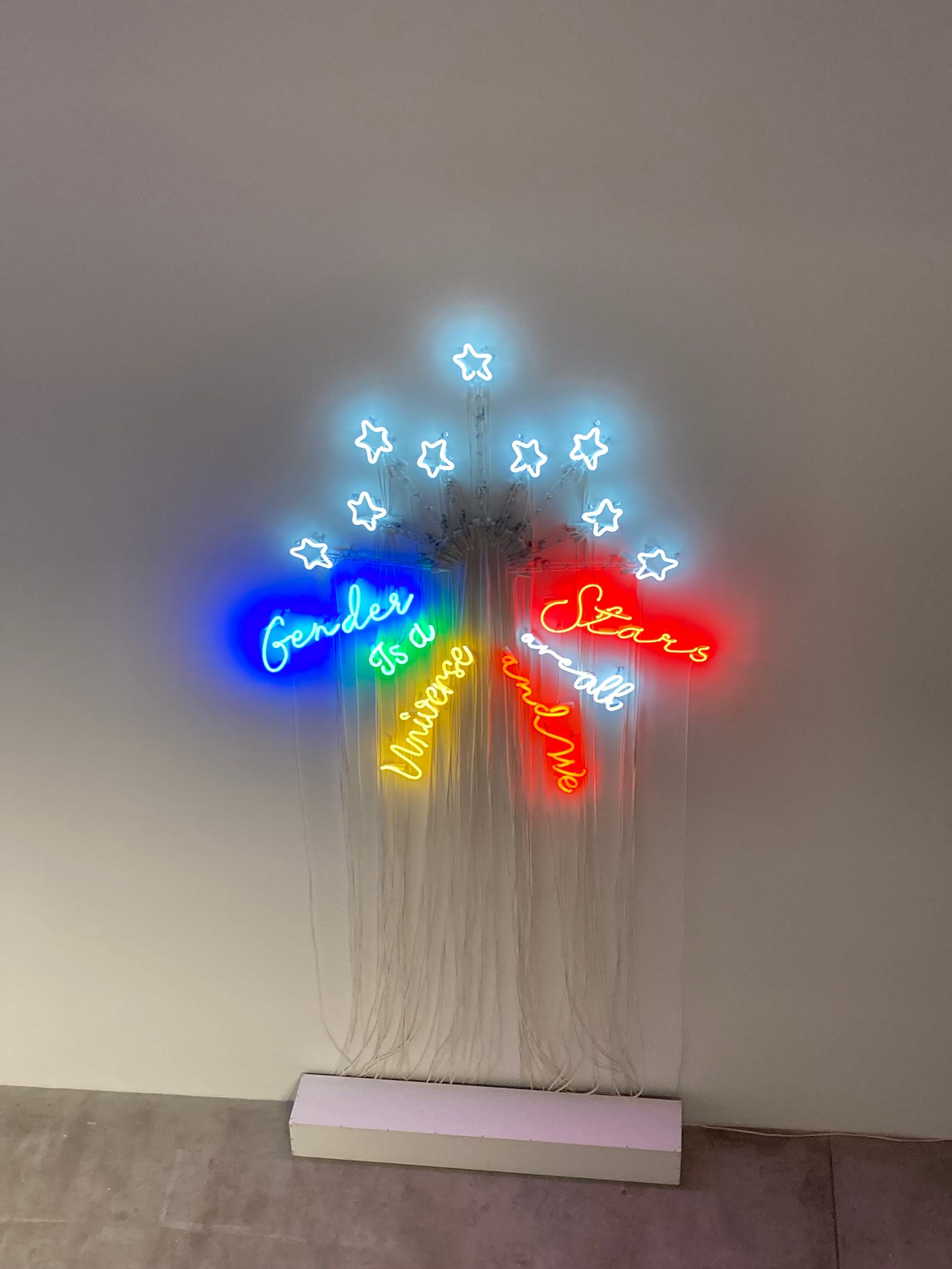

If you would like to see an example of bludgeoningly unsubtle art, visit Andrea Bowers’s show at Andrew Kreps, which is a crushing embrace of normie liberal pieties around the subject of trans rights and representation. It’s almost grotesquely well-meaning, evincing a garish aesthetic that seems plausibly offensive to those whom the show would seem to champion—rotating disco balls nest within baroque glowing neon wall medallions or chandeliers, with the mirrorballs bearing illuminated phrases like blah-blah BE YOURSELF or blah-blah-blah COMMUNITY. (Curiously enough, only a wholesome video still appears to be available on the gallery’s website, though the available PDF has thumbails.) It’s the sort of art I imagine is featured on daytime television. At one point in Bowers’s career, it seemed as if she was engaging in a kind of cataloguing of political discourse, almost sociology. But if you do the bit long enough, the bit starts to do you.

For counterpoint, stroll down the street to the Amina Ross show at Someday, which verges on the cryptic but rewards your decoding. Its centerpiece is the eighteen-minute looped video carcasse/underglass (2023). Effectively nauseating and stylistically jarring, the largest chunk of screen time goes to a butcher describing in gnarly voiceiver what he does with a whole hog when it arrives at his doorstep. A sample step in the dismemberment process: “Sometimes you can take either side of the pig’s jaw in your hand and just like use both your hands to snap the head off.” It’s enough to put you off your weisswurst—and on its face, not entirely subtle, either.

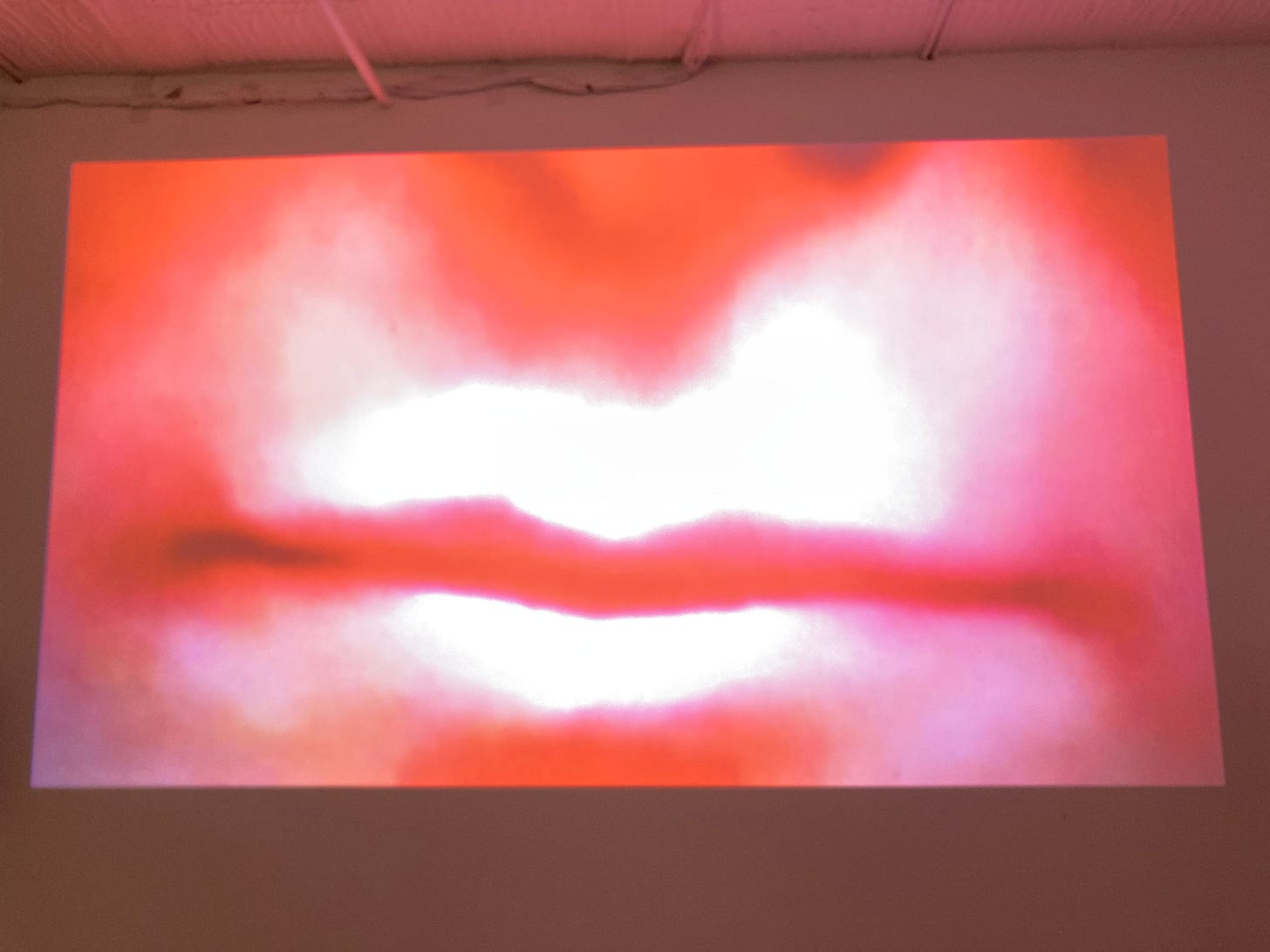

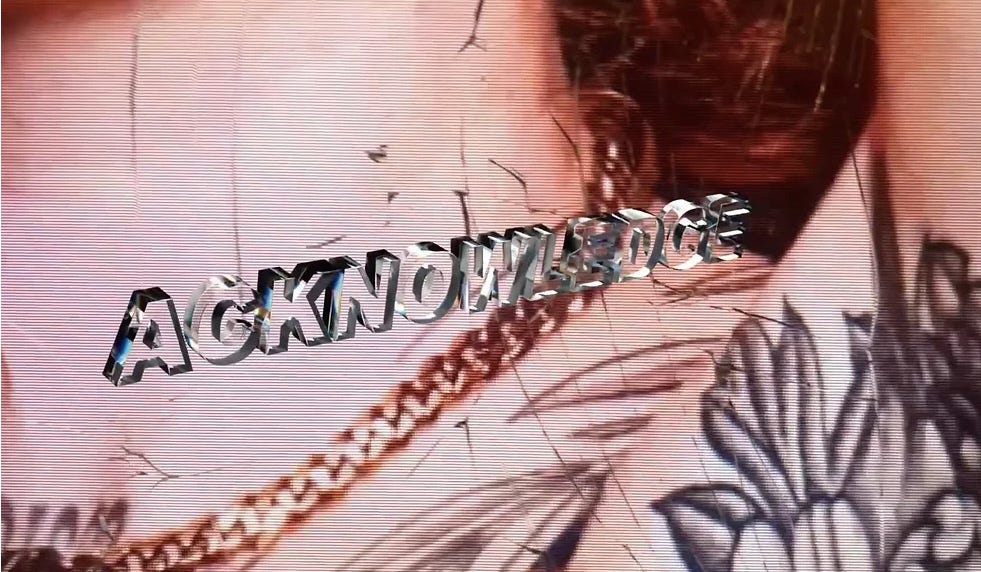

Compounding the monologue’s visceral quality, however, it’s delivered over a shifting brown-and red abstract field, which reveals itself to be open lips, a mouth that doubles as wound—but one that sucks a red lollipop. It’s the first of a few jump cuts in mood that accrue between segments of the piece. Another portion of carcasse/underglass has a post-Dis magazine quality, taking place in a digital sky where clunky 3D renderings of words share the clouds with hunks of architecture, and a bird carcass stripped of all meat and most bones flails through the sky as a pair of feathered wings.

The monologue in this part of the video, delivered in a chipper, lightly computerized voice, relates the weight of being watched, surveilled, “the mundane terror of living in a world with police.” But so too does it relate vignettes like falling into a dressing-room mise-en-abyme as you realize the store hasn’t a shred of garb that fits your body. The mood is one of everyday alienation; in an annotated copy of the script available at the gallery desk, Ross refers to the “heavily weighted eye” and Simone Browne’s book Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. The clash between the seemingly blithe visuals and the meaning-rich language does not, as you might imagine, turn the speech ironic. To the contrary, the language gives the tacky look a kind of gravity, opening up its possibilities. The typography is just the vernacular of recent years, as endemic in the last decade as Ed Ruscha’s signage on view uptown at MoMA was to the sixties. Everything is floating, literally, even as things feel quite grave.

Ross’s metaphorics trend elemental and center on glass, with its multivalent ability to distort or focus. A few pieces take the form of fragile square tiles; a couple of inchoate objects are mounted on rods, little wads of thickly vitreous color that resemble stones or the residue of a smelting pit. Most puzzlingly in a show full of details to connect and decipher, jelly jars and other household vessels line up on the floor against one wall. They contain rainwater collected from gutters. The humble glassware leaps out as the only readymade objects in a context where all the other works emphasize craft, be it glassmaking or turning pigs into pork.

But the jars and tumblers have a completely different function: to hold or preserve. They seem so out of place—a little alienated themselves, perhaps. The vessels invoke ritual, something votive, as well as nature, the cyclical, performance, the passage of time. Ross’s mute untitled work pierces the white cube, whereas if the artist had held a little tighter to a notion of aesthetic unity of facile coherence—that is, transparency—it would have remained sealed and a little airless. If you want to go Barthesian, it’s a quotidian, real-world punctum. It gives the show breath, a contemplative breeze.

The Week in Institutional Rot

Last week, Artforum. This week, Documenta. I have little desire to write about the latest imbroglio at a hallmark art-world institution. Funny though: I’ve actually worked both places. And all I have to show for it is this lousy Substack!

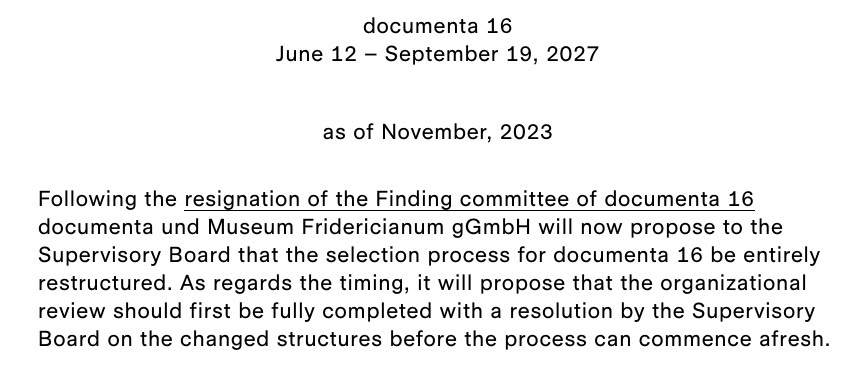

Things do bode ill for the quinquennial, however, now that the entire selection committee for the next artistic director has resigned. As the four last-to-go members of the committee wrote in an open letter—the Pulitzer committee really needs to set up a special award for what’s turning out to be the year’s hallmark literary genre—they feel “grave concern for the future of documenta.” The culture minister is (not for the first time, thanks to rungrupa’s fuckup last time around) questioning the show’s funding, and there’s talk of postponing the exhibition.

I would bet that some neutered and extremely downsized version takes place on schedule in 2027. But then I tend to bet on walking-dead endgames for institutions—the United States, for example.

Lucky for us in New York, a little bit of Kassel is coming to town, in the form of Kassel (2013), a sculpture by the eighty-three-year-old German sculptor Reinhard Mucha, on view at the downtown gallery Francis Irv. His industrial mien is well articulated in Kassel, which resembles a wall-mounted storage unit, and its display at the gallery is a deft extension of the mechanical aesthetic the last show there, by Rachel Fäth. Mucha’s title might seem insidery, but I suspect it’s the merger of references to Documenta—a display case for art—and to Kassel’s historic status as a manufacturing hub, notably for the weapons industry.

The work is listed on Artsy, curiously enough. Check it out in person. You don’t see a lot of Luhring Augustine artists in the Chinatown mall, and it might be the closest you come to Kassel in a while.

So You Wanted an Art Magazine

My open call to start a new art mag received a number of intriguing replies. Thank you to everyone who wrote! Let’s see what develops; keep the brainstorms coming.

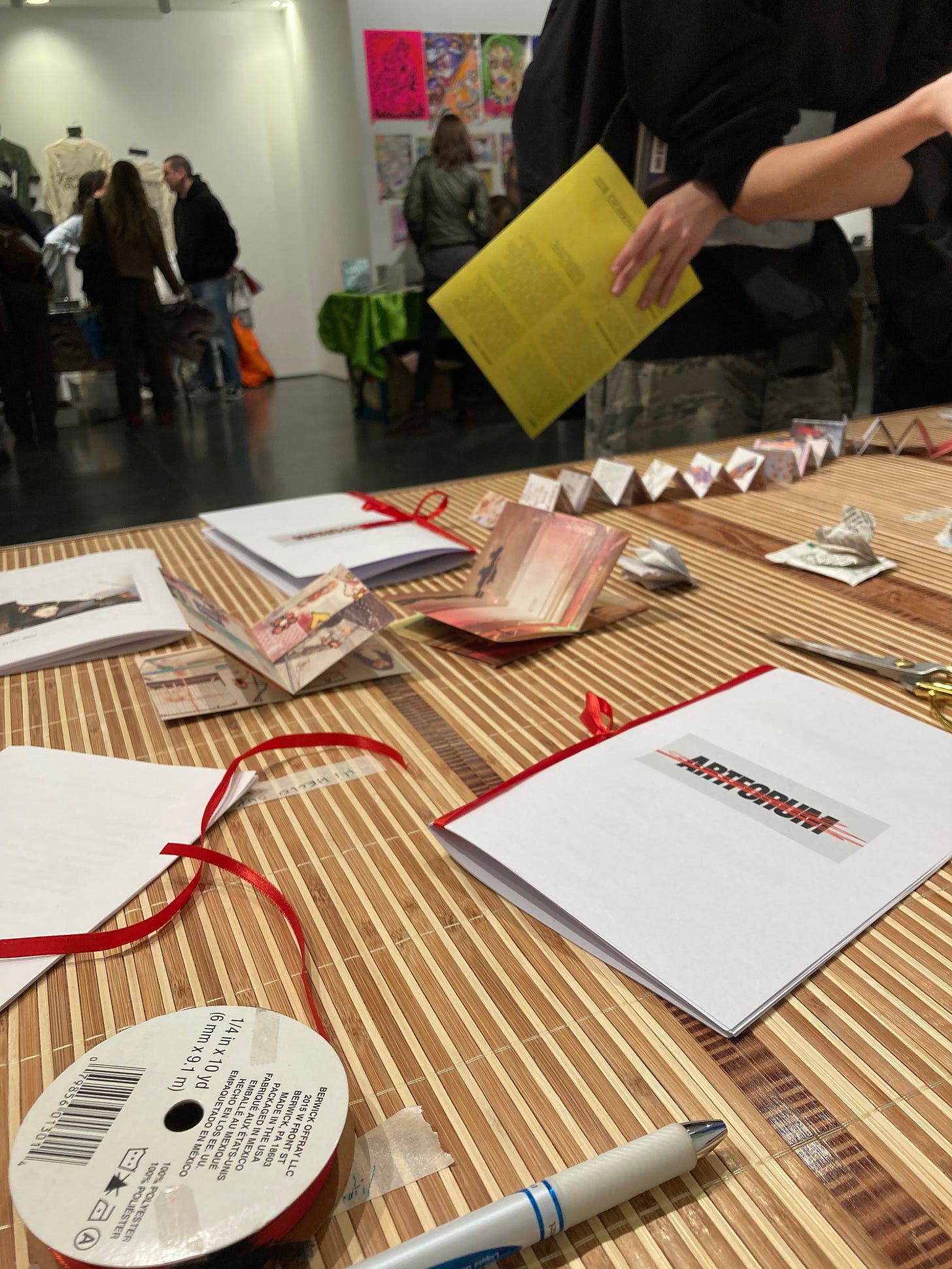

In the interim, to satisfy your thirst for ink-and-pulp critique, behold—Spigot: The Magazine. It debuted last Sunday at Printed Matter’s zine fair at the Brooklyn Museum. Don’t get too excited, however: the publication featured no new writing but rather compiled the two columns I’ve written about Artforum’s arc over the last year. I only made four copies, hand-bound with red ribbon, and all sold out. Success!

My DIY foray happened only due to a nudge from the artist Maggie Lee, a zine maker from way back whose handiwork appears at the Brooklyn Museum in a show that opened last week, Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines. Thank you, Maggie! More of Lee’s work is currently on view at the Whitney; her fantastic video Mommy is part of the new collection hang on the sixth floor. And if you happen to be wintering in Switzerland, she’s having a show at the Kunsthalle Zurich in February.

Wine

The tradition of American pinot noir with Thanksgiving turkey is yet another institution ripe for collapse. To me, the wines are little fruity, kind of silky, but not too much of anything, their inoffensiveness no doubt part of their appeal.

This November, cast off conventional wisdom. Instead of rushing to the Russian River Valley, try a Burgundy, which is also made from pinot. (If that info is too remedial for you, sorry. It took me years to figure this stuff out.) I’m always surprised by how much more dense even lower-end Burgundies taste than their American counterparts; as a person at a wine store recently put it, they have a lot more “tertiary flavors.” That is, they can be weirder. If you do buy Burgundy, again flout conventional wisdom and decant it for a little while—no one reading Spigot is going to be buying vintages so precious that you need to worry about the phenols that begin leaching off the second you open the bottle. (If you are, invite me over.) See how it’s doing at thirty minutes, but you might want twice that.

Burgundies aren’t completely cheap though. More bang-for-buck alternatives: Beaujolais, which also super agreeable, but instead of pinot’s velour texture, it’s crunchy or flowery. You could experiment with lighter Italian reds, like Schiava from the north or Frappato from Sicily, if your menu doesn’t go too hard on the creamy casseroles. An even more outré possibility: Xinomavro from Greece, but it absolutely has to be one that’s low in tannins. One that’s excellent is called Thymiopoulos, though I’ve only seen it at a couple stores in New York, including this one in Park Slope.

Music

I forget where I recently came across Juliette Gréco, but she just sounds good right now, with the early dark and the steady rain falling outside.

Sad I wasn’t able to get a zine last weekend! 🥴