Emo-Abstraction

Cathy Wilkes, American Football, psychoactive rosé, and the surprise return of staged-narrative photography

This time of year essentially demands that I write something topical instead of remote and essayistic. Yet the pace of the first week of “the season”—art season, fashion season, the fall season, the season of increasing darkness and mounting despair—was even more counterproductive to writing topically on art than being out of town. The running around I did recently is chronicled at Artforum.com. There are one or two mean jokes; DM or write for the meaner ones that I cut. Paying subscribers only!

Also I saw a few things at slightly greater length. One that stood out is Cathy Wilkes at Ortuzar Projects.

Wilkes isn’t exactly obscure—she represented the UK at the 2019 Venice Biennale—but she shows infrequently in New York, her last appearance being a gripping presentation at PS1 in 2017. That one featured mannequins, which led me, an idiot, to premature Genzken associations. While the two artists might be equally cryptic—and Genzken no doubt encodes her own level of psychodrama—Wilkes’s figuration goes in many other directions, and her tableaux focus on the domestic and the narrative, using objects she collects over time.

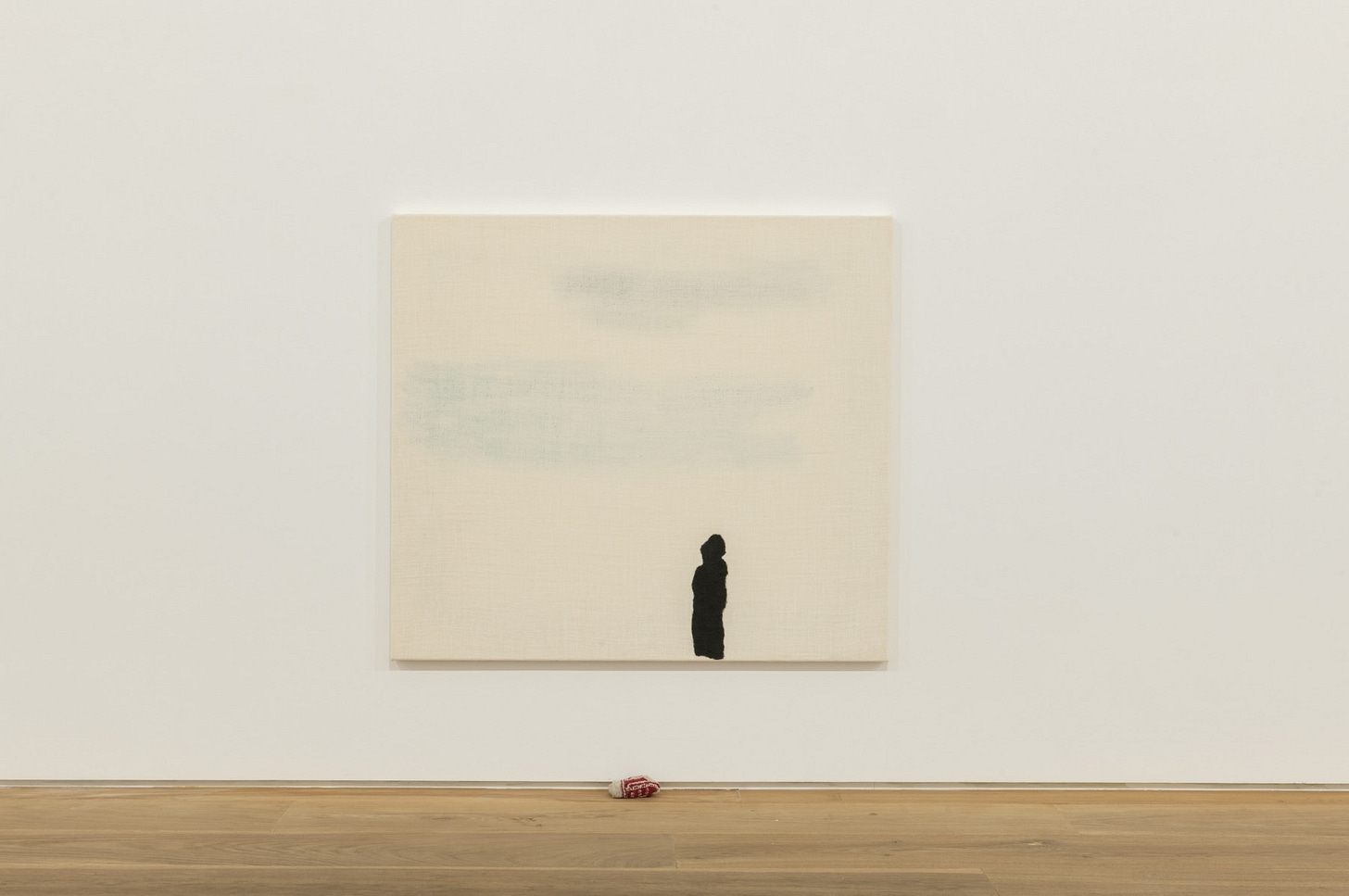

That may sound worrisomely likely to result in something bathetic, I realize, but it’s quite the opposite—one of the reasons I like Wilkes so much, I think. She keeps her installations spare; the show at Ortuzar qualifies as austere. A one-legged, life-size, probably female papier-mâché figure with see-through hands and a painted-on tonsure stands uncomfortably at the center of the gallery; around the perimeter, a suite of canvases hangs very low on the wall. I regret to confess that my first thought was that they are at dog level.

They are, of course, at the height of a toddler, and they bear various anti-Gestalt arrays of thin paint marks that a toddler might make—clouds, patches, scribbles, strips, strokes, sometimes leaving the canvas looking like the back of your hand after you leave a makeup store. Interspersed on the floor among the paintings are a few domestic objects: a shallow bowl, a vase. The overall scenario is like the archetypal one of a child having scribbled naughtily on the walls, inviting punishment—except that the walls have been preserved by the canvases. The punishment has been forestalled by the canvases, though perhaps only with the conversion of the experience into art.

Wilkes structures her installations with an acute spatial sense. I imagine her staying up all night before a show shifting a glass cruet half an inch left, half an inch right, over and over again. Her focus is kept squarely within the prison of the home, but because the objects are so uninflected, the results are abstract—perfectly so, such that walking into a Wilkes show is wading into a gray haze into which you diffuse a little. You’re not sure how whether you should read things as rawly emotive or even personal or if you should look at it through a more postconceptualist lens. In this tension placed familiar correlations of mood and mode, it reminds me just a tiny bit of the Pryde show I mentioned last week.

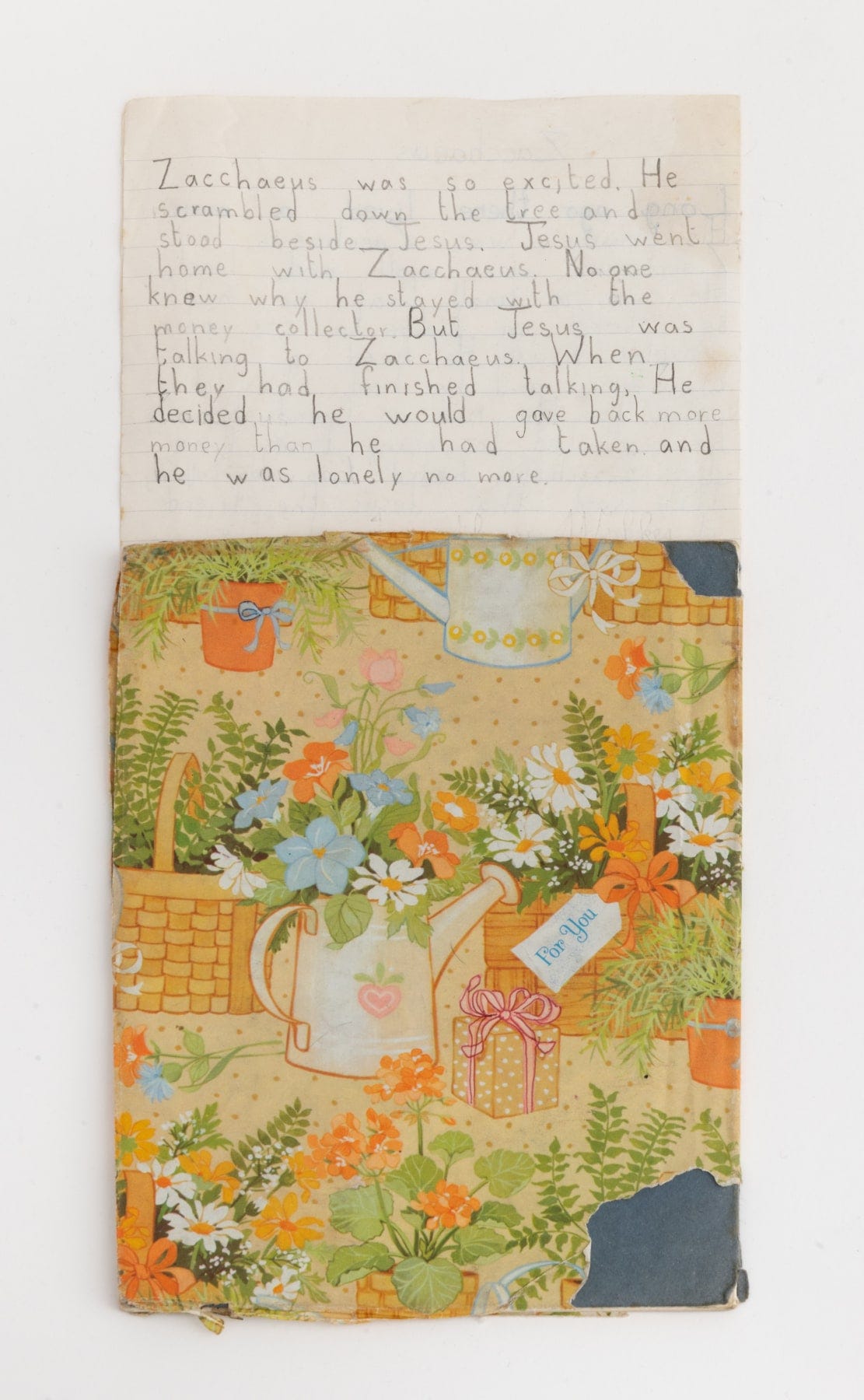

At Ortuzar there are two vitrines. Each contains a mutely disturbing triptych; their collective contents include pencil drawings of a flower in lush bloom and prosceniumlike displays of curtains; a tiny square of what I think is carpet fabric; a page from a child’s notebook discussing the Biblical tale of Zacchaeus, who is redeemed from sin and delivered from loneliness by Jesus; and a tiny, violating polaroid of what appears to be the crotch of a girl wearing white underwear. A lot of the art I like is a puzzle of one sort or another, ideally an insoluble one. That applies to Wilkes and especially these vitrines. The items are laid out like troubling evidence from which no certain deduction can take place. Which is very much a synecdoche for Wilkes’s art overall.

Thank you to the kind people who sent me Wilkes photos, even though I didn’t use them.

The Return of Staged Narrative Photography

Coming October 21, 2022

Wine

Famille Sumeire Le Rosé de S. Méditerranée 2020. I drank a lot of different things on Saturday night, but of all the wines I consumed this one was easily the best. Of course this photo was taken at 3:27 am on Sunday morning, so at that point, tap water tasted pretty amazing. Provence rosés usually strike me as smarmy and fake-sophisticated like an herb mix from a plastic shaker but it turns out this wine is 40 percent Cinsault, which gives it the grainy, mountain-spring quality that tends to be my baseline preference. At the time I was sure a bottle of Le Rosé de S. cost like five hundred dollars, but in fact it’s very cheap for the degree of pleasure I derived from it, solidly under twenty bucks if you can find it. May its powers sustain beyond the light of the Pisces moon.

Music

Welcome to autumn. It’s football season.