Ethnonational Ultrarealism

Buck Ellison sucks. Plus Leslie Winer, Joy Williams, and a Riesling named Bruno

We live in a time of paradox, an era of caustic skepticism toward the obvious and ludicrous credulity toward the occult. Even Spigot is not immune to such cultural tides, dear reader. For example, in the face of substantial evidence to the contrary, I prefer to believe that the artist known as CumWizard69420, recently on view at Cheim & Read and deftly, er, acknowledged in Artforum, is in fact Mathieu Malouf. It’s just more fun that way.

Likewise I find it hard to shake my belief that Buck Ellison, an artist who, according to his press materials, creates “a deep network of inquiry into . . . whiteness,” is a fictional character created by some POC artist pulling a reverse Woolford. Buck Ellison is the name of a supporting character on Yellowstone, not someone who went to Städelschule.

Nevertheless, Ellison does seem to be an actual human being; I’ve inquired with people who’ve worked with him. They insist that he exists and moreover that his whole shtick is not a joke.

I heard of Ellison at the same time most people did, a couple years ago when he burst into view with appearances in the 2020 Made in LA and the 2021 Whitney Biennial. In both exhibitions, he showed stock-photo-styled re-creations of the lives of the uber-rich, fanatically conservative Prince/DeVos families, whose number include Betsy DeVos, the Trump Administration Secretary of Ed, and Erik Prince, the founder of Blackwater and a general rabid freak. Currently Ellison has a show up at Luhring Augustine in Chelsea through the end of the month, with Erik as its muse.

The exhibition is called Little Brother, invoking both Prince’s blood business and class violence by obliquely conjuring the A-bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Unfortunately that sly bit of punning is the highlight of the proceedings, which comprises six photos, a two-minute video, and some wallpaper made between 2017 and 2022. The decision to show such a paucity of work as an NYC gallery debut is mystifying, particularly since it’s all familiar. If you know anything about Ellison, you know the routine, and so you’re treated to images of a generically handsome model posing as a Clausewitz-clutching frat-boy: the new poster child for the banality of evil.

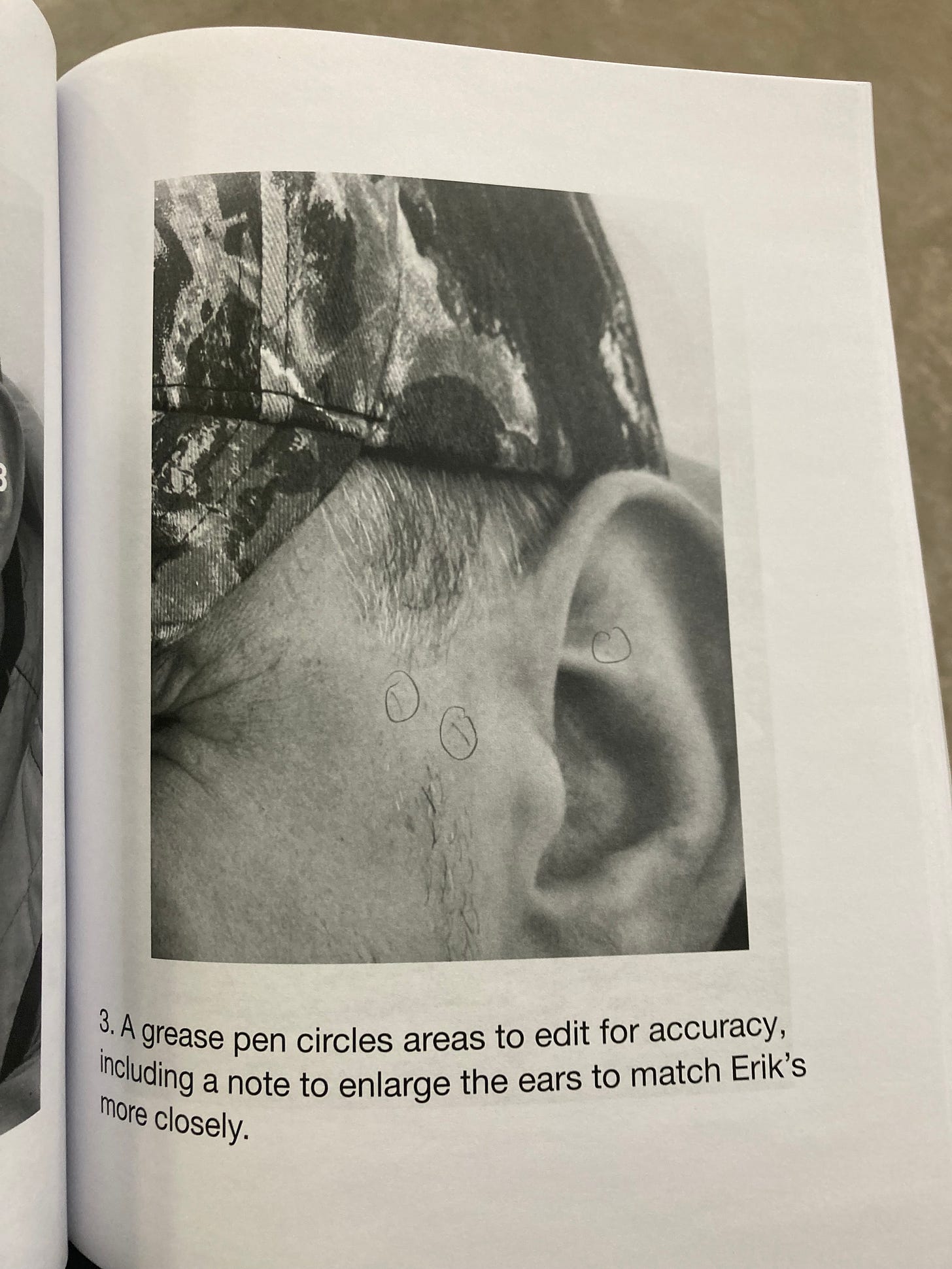

There’s no inherent reason Ellison’s work couldn’t be worthwhile. The problem is that it’s numb and humorless. It frames a lack of imagination as a virtue: The photographs (and the video, which is essentially a sizzle reel for the still images) rest their claim to artistic quality in a Crewdsonesque obsession with production value, a sense that precision is an end unto itself. Ellison published a book to accompany the series, a volume whose primary purpose seems to be to prove how hard the artist tried to make things “real.” When not highlighting the stray hairs removed from the Prince stand-in’s scruff, the book helpfully tells you how to look at the images: “Erik’s body is blurred, inviting the viewer to focus instead on the glut of archival images culled from research (a photograph of his family’s yacht, a postcard written to friends, a note on U.S. Navy letterhead).” Just in case you suck at looking.

The rest of Ellison’s oeuvre is all the same—a tween in a stars-and-stripes leotard striking a gymnastic pose on an antique cannon, white bros in fleece vests shot à la Thomas Ruff. You would get much more from strolling a few blocks through Chelsea to the Tina Barney show at Kasmin Gallery, who merely shoots her own wealthy, if not uber-rich, milieu and has made far more compelling work than anything Ellison has produced. In either case, could we look to a class beyond that of White Lotus or Succession for our entertainment for a change?

Could Ellison be trying to make more complicated, interesting points about the whole notion of fidelity to reality, for example—even the dreaded jujitsu flip into “irony”? He evinces barely a shred of curiosity about such concepts in either his press materials or his book. And if so, why choose Prince? Like the New York Times visiting a Rust Belt diner, the artist claims seek insight into the darkness: in Ellison’s words, “not to forgive, but to claw towards precision and understanding with a gentle heart.” It’s a coy justification, practically Christian.

Ellison is making work that’s easy to hate, which he surely must realize. Leaning into it deadpan seems like a troll. Wearingly, though, it works on people. During the run of his show he’ll be appearing at a couple universities near you, Princeton and NYU, via the IFA. (If that isn’t enough Whiteness Studies for you, you can warm up in New Haven: some grad-school gulls similarly thought it was just so fascinating to invite Matthew Gadsda to Yale.) His appeal to grandees is both predictable and disappointing; his work makes a number of pushbutton art-historical references, it’s slickly produced, it gives you something to argue about, and it’s unique—I’ll give him that. Filling a niche in an intellectual marketplace isn’t making good work, though. But it might get you some attention.

Books

The greatest living American writer, from 1990. You can check out the ruthless title story, courtesy Granta.

Wine

Karthäuserhof Bruno Riesling Kabinett. Most Riesling you get in the US has the texture of Jell-O and tastes like it’s had a couple tablespoons of sugar dumped in it; the Germans keep all the good shit for themselves to drink while they nibble white asparagus and watch watersports videos. Meanwhile they send us the Fruity Pebbles of Weißwein because it appeals to our juvenile American palates. It goes with our taste for incest porn.

I did not expect, therefore, to pick up a bottle of Riesling when I walked into Leisir Wine in the shadow of the Manhattan Bridge on NYC’s Henry Street. In fact I wasn’t going to walk into Leisir at all because of its signage, which advertises its natural, biodynamic, and organic wares in a graphic-design style I would describe as “electric Gaia.” But I bravely try to subdue my petty biases on occasion—and it was hot on Saturday—so I ducked inside.

It turns out Leisir is a great little store with a selection that to my untrained eye focuses less on the screwball soda-pop skin-contact end of the natural-wine spectrum and more on varietals done in exacting ways. The person working there, Autumn (if I have their name right), gave me great advice, pegging me immediately as the kind of person who’d be excited about a wine was named after a Carthusian monk.

The secret to good Riesling is that its sweetness is more in the nose than on the palate. Bruno smells and tastes like honeysuckle and tart apple but in a complex, latticed way; it’s technically off-dry but it also has a nettlesome quality, with a thousand little pinpricks. (Is that what they mean by “racy acidity”?) It’s fresh and minerally but instead of sea salt or creekbed it’s like you’re actual metal flakes landing on your tongue.

So visit Leisir, try Bruno. Shoutout to Autumn, who also told me what’s trending these days (NY state wines, apparently), explained that Bruno has that tiny label on the neck they can chill it in the Möselle, and humored my rude complaints that oeno bros are turning natural wines into the new IPAs.

Music

Leslie Winer made what’s arguably the first trip-hop album, but I had never heard of her until Craig Kalpakjian’s new show at Kai Matsumiya, which takes its title from one of one of her lyrics—Even a small boat typically casts a wide debris field. It’s unsurprising that Kalpakjian, accomplished as a musician as well as an artist, would pull something from the crates and make such a nod in his exhibition.

Winer is a fascinating character: she came to New York in the 1980s with inclinations toward art and music (studying at SVA with Hannah Wilke and Joseph Kosuth, if Wikipedia can be trusted) and fell in with Burroughs, Basquiat, et al. She quickly got work as a model in campaigns for Valentino, Dior, Yohji Yamamoto, and Gautier—and, apparently, a bit of a heroin habit—then before long moved to the UK and the world of Leigh Bowery, et al.

In the early ’90s, Winer turned to music. Her 1993 debut, Witch, lives very much at the era’s convergence of dub and spoken word. The instrumentation is sparse but insistent, the vocals variously musing, insinuating, or angry: for the former, check out the seductive “Skin,” for the latter “In 1 Ear” (and cf. Winer’s gleeful album-cover riff on the famous photo of Johnny Cash giving the finger to the warden at San Quentin). Winer uses her voice as a rhythm instrument and a dramatis persona, her lyrics atmospheric and abstruse in their poetic impulses, delivered with the slightest hint of Burroughs’s deadpan drawl.

Winer is currently living in France and still making music. Light in the Attic put out a compilation of her work, When I Hit You—You’ll Feel It, in 2021. Witch, meanwhile, is still due for a reissue.

For Kalpakjian, the Winer citation seems linked to a group of drawings that show fields of text from sources like Kafka and Proust floating against inky expanses. But the other body of work at Matsuimaya is apt in its own way. A series of paintings in UV pigment depicts the motif of the horizon over the ocean with a nauseating ultrarealism. Kalpakjian’s unreal waves and Winer’s relentless oscillations make a strangely visceral duet.

Thanks for writing these. Favorite column on the internet!

Is the Riesling named after the Sacha Baron Cohen film? Just thought I’d ask