House of Balloons (and Pies)

A visit to Los Angeles. Featuring Juliana Halpert/Parker Ito and le bistro Taix. Plus "Speak Now (Taylor's Version)."

Spigot visited Los Angeles recently and soaked up all the spacey bonhomie of the locals: if relational aesthetics is back, as it unfortunately seems to be, why not site-specificity? Therefore I “went native” and soon grew reluctant to leave the house. I met one minor celebrity and ate four psilocybin mushrooms, which is about average for an LA visit, I guess. I spent an afternoon at the Los Feliz branch of the Coffee Bean and Tea Leaf waiting for my Tedros Tedros to walk through the door, but instead only leafed idly through the collected Patrick Melrose novels, which has without a doubt affected this edition’s prose.

I’m sorry, Angelenos. Your reading experience is going to be super annoying this week.

The most distinctive art show I visited, just before it closed, was a two-hander at Bel Ami, Juliana Halpert and Parker Ito. The exhibition was explicit about being rooted in their friendship rather than any specific curatorial thesis, which was a welcome abandonment of the shoehorning justifications that are practically mandatory for group shows. It’s a fine line between the contingent and the incoherent, of course—what am I supposed to do with Syphillis Too (II)?—but Halpert and Ito stayed on the point-scoring side of the stripe.

The show, titled Au Jus, broke into two separately entered sections. The first opened with a big, thick, pastel Jules Olitski painting that, if I understand correctly, usually hangs like a wall of pink and teal stucco in Ito’s home. Around the room were a couple of Halpert’s photos from an orchid show, attending less to the flowers than the awkward spatiality of the venue and the nondescript individuals presenting them. There was also one print in gelatin silver of a friend of hers that took an opposite approach, of tender scrutiny. In the suite’s adjacent room, two walls held a number of Ito’s baffling paintings, ugly mediated and hyperconscious abstractions hung edge to edge and low. Within them, they contained images of ancient and Christian statuary, a Académie mademoiselle and a digitally distended anime madchen, all breaking out in clunky, captivating layout.

The thematics were subtle, but there did emerge from the collective works a sense that you can pursue beauty, that most hackneyed of concepts, in an everyday way like joining a flower club or taking pictures of a flower club or thinking about old aesthetic ideals from pictures in art books or inventing new ones from stuff you found on the internet. My favorite work in the whole show was a found photo-rolodex filled with Halpert’s new three-by-five C-prints of flowers on her nightstand and other domestic still lifes. They gave me a little feeling of Josephine Pryde’s The Tiled Shelf Ran the Length of the Bathroom (2021/22), a tremor of processed disquiet and maintenance.

Down the hall, the second part of the show was by contrast a dark room, lit mostly by two of Ito’s works: a scanner occasionally flashing on a figurine and an irresistible détourned nature video—soundtracked to something like a David Attenborough club remix—of a hummingbird morphing digitally as it flits and the camera moves in and out of focus. A figure for a certain kind of contemporary artist, perhaps, sucking a little nectar and shifting shapes; the kind of artist I like.

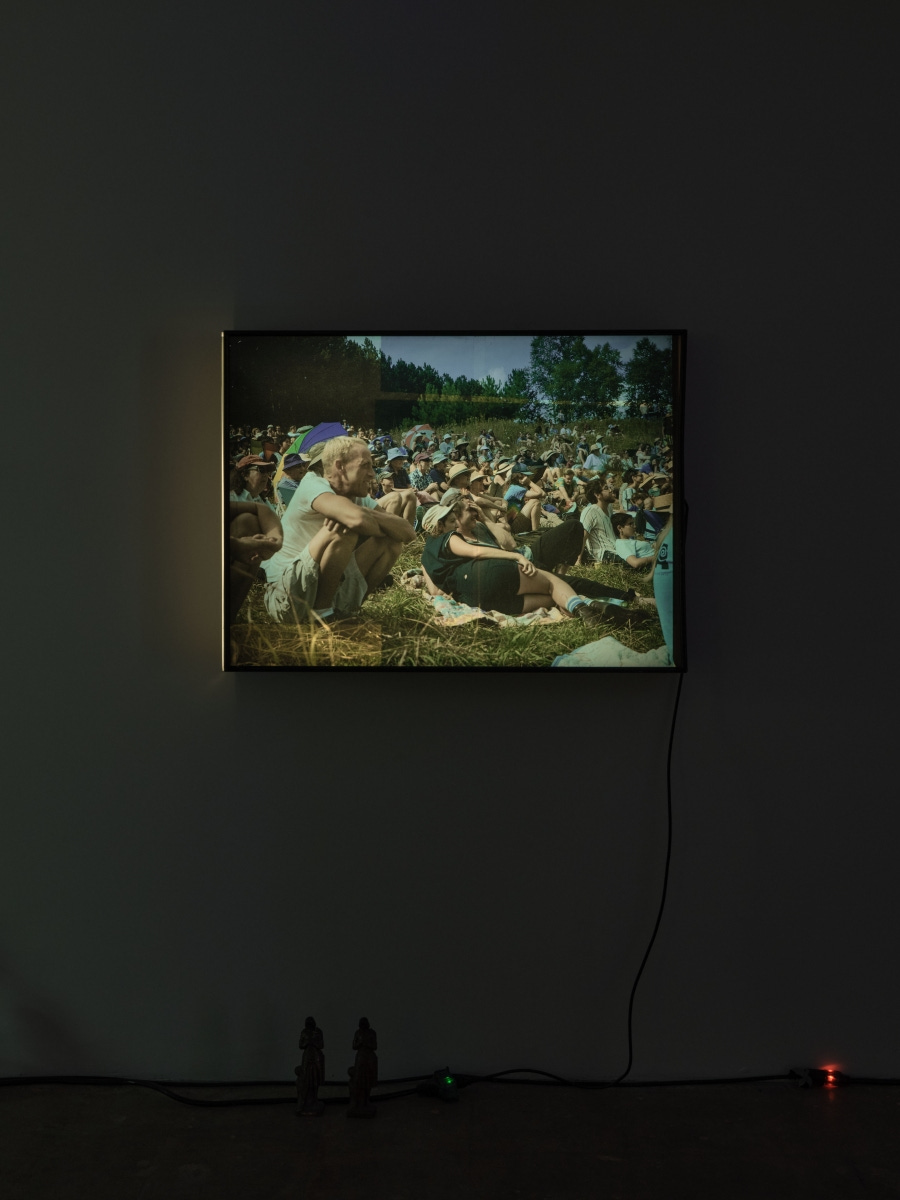

Meanwhile on the floor around the perimeter of the dim room were, surprisingly, live plants with Ito-cast appurtenances, plus other items from the artists’ homes. A few odd lightbox photos by Halpert glowed on the walls—a pair of senior-citizen twins, an audience splayed rustic in the grass at a music festival. Connections were again present and subtle, with the room’s tilt toward nature and technology coming as if it arose through chance and affinity rather than any imposition.

Not every show can operate like Au Jus; not every pair of artists can spin the delicate but unmistakable web of connection that close association unconsciously brings. That netting is what would lead me to call the show and its awkward arrangements beautiful.

Above: Parker Ito, The World Outside by Jay Israelson, 2021–23. Installation view, Au Jus, Bel Ami, Los Angeles, 2023

Wine

The sauvignon blanc at Taix. On this trip to Los Angeles, I decided to settle something once and for all: how do you pronounce the name of the venerable restaurant Taix? Is it Tie-eeks? Tay? Some other, secret third phonemic?

To put it in New York terms—as I must!—the Echo Park bistro is basically Lucien crossed with Odeon minus the cliché power games and a little grimy-hornier. If you want to be seen as desirable, go to those NYC establishments; if you want to fuck, go to Taix. The wistful deserted cavernous dark-wood-and-red-leather place possesses something like four separate dining rooms—does anyone use them?—but the restaurant’s true focal point is the lounge. In its precincts Spigot fan Gracie H., the honorary mayor of Los Angeles, may frequently be found holding court, and the Dodgers are always on TV regardless of the time of day, month, season, or decade.

Taix is a gin-and-vodka kind of place; you would have to be an idiot to order the wine. That’s where I come in.

Our server graciously allowed me to try the sauvignon blanc, which prompted me to order a dirty martini. With my palate suitably benumbed, I went for my second and subsequent drinks with the sauvignon, which was really totally fine in the liter-and-a-half way of eatery house booze—better in fact, a little saltier and gamier than it had to be and actually imported from France. Unfortunately I didn’t get its name, and the menu online isn’t too elucidating. You can however feel safe ordering it without spoiling your experience of the charcuterie, since, like the vin, the meat and cheese plate seemed to come straight from Gelson’s, arrayed as if it had been inverted wholesale from a plastic tray.

I kid, I kid! I love the Eastside, the Westside, the Valley, and the Canyons. Also I love Taix. Like all of my favorite restaurants, the food is secondary. In LA what often seems to is the contrast between the dark dining room and the bright sky outside. At this point I feel like I get a lot more sense of history in Los Angeles than I do in New York, which should be ironic but really isn’t.

Oh and apparently you say it Tex, which I guess makes sense since the city seems never to have figured out how to pronounce Los Feliz, let alone its own name.

Music

Though my admiration for Taylor Swift’s rerecording project has not waned, my enthusiasm for dissecting the results has, since they offer so little in the way of interpretation (hers and, as a result, mine). Nevertheless I have a certain reputation to uphold. And so I lay on the floor of my host’s apartment one night and bluetoothed Speak Now redux to a pair of mammoth speakers low in the Hollywood Hills.

Within their procrustean prescribed range, the minutiae on the new Speak Now seem to take more liberties than the details on the previous re-recordings—the laugh in the title track seems richer, longer, and certainly more knowing. The piano on “Dear John” is moved forward, its pedal steel accents clearer, the song slower, as if she knows—and oh does she—that she can take her time twisting the knife. The delicious parody of the track’s guitar frills is teased up just enough to make me imagine that this time around she hired Gene Ween.

Speak Now has always seemed flat to me as a recording but in a way that was important to its power; its stridency and thinness was adolescent, but potently so. With all the arrangements clarified here, I miss that feeling, though it’s hardly a dealbreaker. The refractions of the double retrospection that occur—with “Long Live” for example, or “Mean”—are more resonant than on the original, as the future self she predicted at seventeen lenses the real future self she has become. The message is time, as it always is with these albums, what lasts and what doesn’t, the gleaming surfaces of the music resistant to any Ozymandian sands.

A couple of the Vault tracks are really good. The most aberrant and most fantastic is the eighties-sounding “I Can See You,” with its reverberating flat guitar and a touch of ELO electro-twee, the main riff sounding a lot like the Clash. It absolutely slays. I can’t entirely believe it’s From the Vault—the setup seems to be a professional relationship turned romantic—but I also don’t care.

The final song of all, “Timeless,” is one of her oft-hokey narrative tracks and involves items found in an antique shop, so YMMV, but I loved it. It’s the story of a romance that not only outlasts time in the familiar ways but transcends it, and it gains gravity by its positioning last on the record. The most awkwardly appreciated part of Swift’s work, and a part crucial to her greatness, is her ability to write about not just loss but regret, not the issue of right and wrong but the way things naturally fall apart. When she does the opposite and banishes those possibilities from her imagination, as she does in “Timeless,” I find my eyes mist, because in the face of a colder reality, it’s what we all do too.