"Little by little, I felt it going limp."

Javier Téllez's absurdist anti-authoritarianism and brilliant Fascist/commie/Catholic snob Curzio Malaparte. Plus the megagallery peddling Malaparte's furniture.

It’s been a slow few weeks, a gluey indistinct period with humidity that resembles the effects of trazodone, an antipsychotic prescribed off-label for sleep problems. It leaves one a little nauseous, moving through invisible sheets of spiderweb, and with a whacked inner ear. You keep trying to blink a film off your eyes. I’d rather lie on the floor all day than leave the apartment.

One thing you must brave the heat to see, however—provided you live in New York—is Javier Téllez’s new film AMERIKA, on view through this Sunday, August 11, at CARA in the West Village. Téllez is a brilliant filmmaker and artist whose work has been featured in Documenta, the Whitney Biennial, and not one but two Venice Biennales but is seen far too rarely in New York. (Full disclosure: he also happens to be my ex-roommate.)

AMERIKA takes up a Chaplinesque protagonist in riffs on the Little Tramp’s films including The Immigrant (1917), Modern Times (1936), and The Great Dictator (1940), montaged with Téllez’s familiar absurdist cast into scenes related to state power and those at its margins and mercy; you can see the influence of not only Buñuel but also Artaud. Téllez frequently works with nonactors, including psychiatric patients; here, the cast (who collectively authored the script with the director) is a group of Venezuelan refugees living in New York. It is no coincidence that Téllez is himself a Venezuelan expatriate of many years.

The film is complemented by sculptural work characterized by Téllez’s wit and wordplay. But the film is the centerpiece. It’s rare to walk into a space for contemporary art and see moving-image work that not only feels perfectly contemporary but also feels like cinema, down to the artist-commissioned red-velvet curtains. (Among Téllez’s pastimes is running a hush-hush private screening club of his collection of 16mm reels.) Park yourself in CARA’s theater for AMERIKA’s half-hour running time. After all, nothing is better in the summer than an air-conditioned theater.

Books

The Skin (1949) by Curzio Malaparte. People have been telling me to read The Skin for years. Then, at a recent reception thrown by Kurimanzutto, I ran into the legendary gallerist (and photographer) Janice Guy, formerly of Murray Guy and now of Higher Pictures, an outstanding photo gallery located in Dumbo. When Guy caught my surname, we started discussing the old country. Turns out she lived and worked in Naples in the early 1980s, an archetypally disordered time in a famously chaotic city. Naturally our conversation turned to La pelle, The Skin.

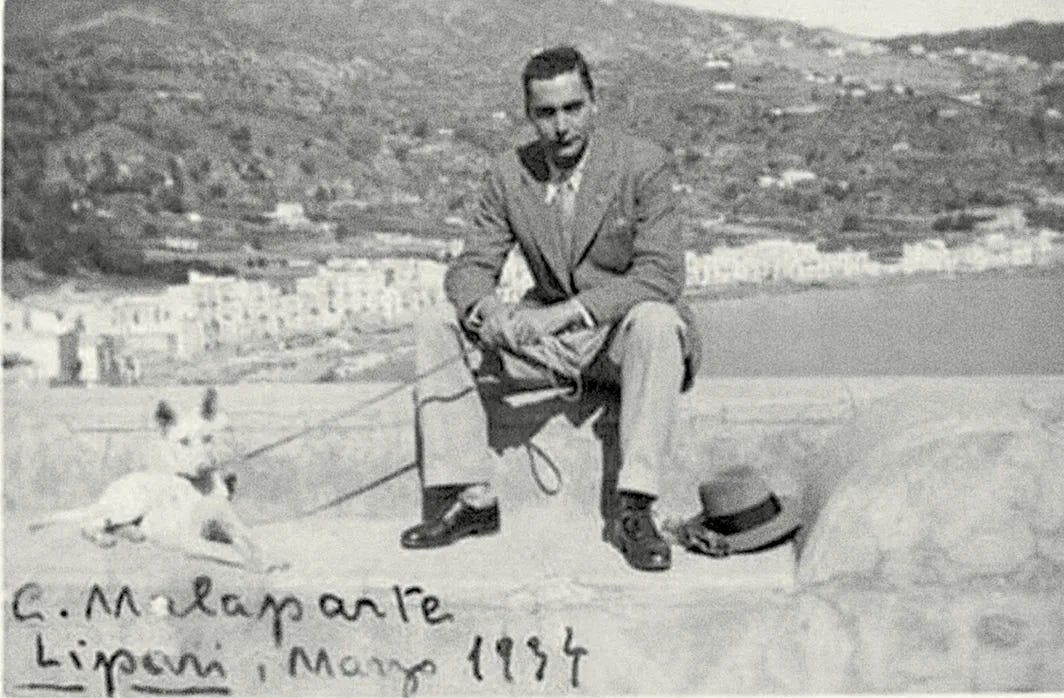

The Italian author and journalist Curzio Malaparte (born Kurt Erich Suckert) was a Fascist early on, starting in the 1920s, then later got himself expelled from the party and jailed. All in all, he was an ambivalent character, joining the Communist Party after the war and converting to Catholicism on his deathbed. His surname de plume means “on the wrong side,” and as a writer, he’s diabolical. Malaparte’s gaze is unstinting regardless of the horrors at hand, and he writes like an angel—that angel being Lucifer.

The Skin is a first-person account, somewhere between fabulation and reportage, of the US Army arriving in Naples during World War II on their way to conquering Rome. Malaparte is a liaison officer in the newly-on-the-side-of-justice Italian army, who mostly gave up when the winds shifted and left the Germans to try to hold onto the place. He was the scion of textile fortune, and in happier times he tarried with the best families of Italy and France. Thus in the book he has access to two rarified echelons: the European nobility navigating their way haughtily through the mayhem of the war and the US and French officers in charge of the invasion. In his telling, Malaparte is the person who decides by what route the American army enters Rome: riding along with a thinly veiled version of General Mark W. Clark, commander of the Allied invasion, at the head of a column of tanks, he persuades him to take the Via Appia Vecchia, route of conquerors from time immemorial. “I don’t know if it’s the safer way in this particular case,” Malaparte opines, “but it’s certainly the more picturesque.”

This insouciance flows over into Malaparte’s prose, which displays a dandy’s attention to the fine points of appearances (and myriad references to the art-historical canon). His descriptions of the landscape are inordinately frequent and frequently astonishing. He must have taken great pleasure in it; you would never logically spend so much time describing the landscape when dramatic, usually horrifying events are unfolding around you—except as counterpoint, of course:

I averted my face and contemplated that strange rustic carnival, that miniature Watteau painted by Goya. It was a lively, exquisite scene, with the wounded man lying on the ground . . . the ragged, pale, thin girls in the arms of the handsome, pink-faced American soldiers, in the silver olive grove; and all around the bare hills, whose green grass was strewn with red stones, and above, the gray, immemorial sky, ribbed with narrow blue streaks, a sky that was flabby and puckered like the skin of an old woman. And little by little I felt the hand of the dying man turning cold in mine; little by little I felt it going limp.

The raw material of The Skin and the bleakness of Malaparte’s mood come from watching his country being overrun by one set of invaders seeking to get rid of another one. The Italians have been rendered spectators to their own fate—which, of course, they brought upon themselves. Unlike most of them, Malaparte has more than bearable living conditions; psychologically, not so much. His combination of shame, relief, despair, and just plain sadness at how the Neapolitans are suffering and how Italy got itself into this situation in the first place is intense but subtly rendered. He displaces his feelings into the landscape, one thing he does with all that gorgeous prose. Malaparte regularly taunts the Americans he accompanies—particularly a sympathetic former Olympian named Jack who pretentiously wants to speak French to his polyglot liaison and swan at the Gallic officers club—about the folly of the USA’s ascendency and the Americans’s naïvete. Half the time he sounds like a character from Heart of Darkness.

The book has its problems. Malaparte is super racist, for one thing. At times when you run across an ugly passage in an old book, you just raise your eyebrows and keep moving. In The Skin you pull up short any time he mentions Black GIs and North African troops fighting for France. (Of course, all the white people around him are completely racist too.) And his view of homosexuality—he uses the euphemism “Uranians”—is positively hostile. An acquaintance of his from a refined family in the north of Italy is gay, which is tolerated by everyone at his level of society to some degree or another. But when Malaparte runs into him, he goes to the trouble in the midst of a war to confront him about the supposed immorality of his behavior. There’s an entire chapter of the book based around some queer—double entendre intended—ceremony that takes place in a cottage by the beach. The caricatures are nasty, the events actually unbelievable in a book full of things that cause you to question Malaparte’s veracity.

For the most part, though, the book’s outrages are fact-checkable, and sources corroborate that lots of the events depicted actually happened. When the historical anecdotes check out, it makes you buy into the more personal ones, like the gristly, devastating chapter about Malaparte’s beloved greyhound, Febo. The horrors of war result in such appalling sights that, once the author has won your trust, you begin to buy into even the ones involving, say, poaching the Napoli aquarium for fish to feed American dignitaries. And you should: it’s true.

Which leads ultimately back to the title. A thread running through all the grotesqueries you experience is a mounting dread while waiting for Malaparte to reveal what the skin of the title is. And yes, he does let you know.

Interior Design

As if fascist merch wasn’t popular enough these days: Gagosian sells copies of Curzio Malaparte’s furniture, custom designed by the author himself for his iconic villa in the Tyrrhenian Sea.