I’m happy to admit my own ignorance and say I was aware of Raphael Montañez Ortiz only vaguely until a couple weeks ago when I saw his late-late-career retro at El Museo del Barrio in NYC. He’s a fascinating artist who should be more famous and you should all go see the show before it closes on September 11.

If you know anything about Montañez Ortiz, you know him as the chopping-up-pianos guy. Yes, that guy.

It’s weird that the author of 1962’s “Destructionist Manifesto” doesn’t have more juice in the contemporary-art world, because he was right there in New York in the late 1950s and ’60s, the same time foundational figures like Kaprow and the Fluxus artists were cutting off their neckties and Zen painting with their hair and Oldenburg was turning out nonsensical playlets that make the Matt Gadsda turn in theater seem almost welcome.

A native NYer of variously mixed Euro and Indigenous descent whose parents came to the city from Puerto Rico, Montañez Ortiz went to Pratt on the GI Bill as AbEx was dying and Pop ascending. Like Fluxus, et al., he tacked the opposite direction, and he developed his own philosophy of antimaterialism. RMO shared bills with Yoko Ono, he was hooked up across the pond with people like Gustav Metzger, he got himself on TV. He seems like a bit of a crazy motherfucker, in a good way, in a way that often can charm the artworld—but, crucially, not always.

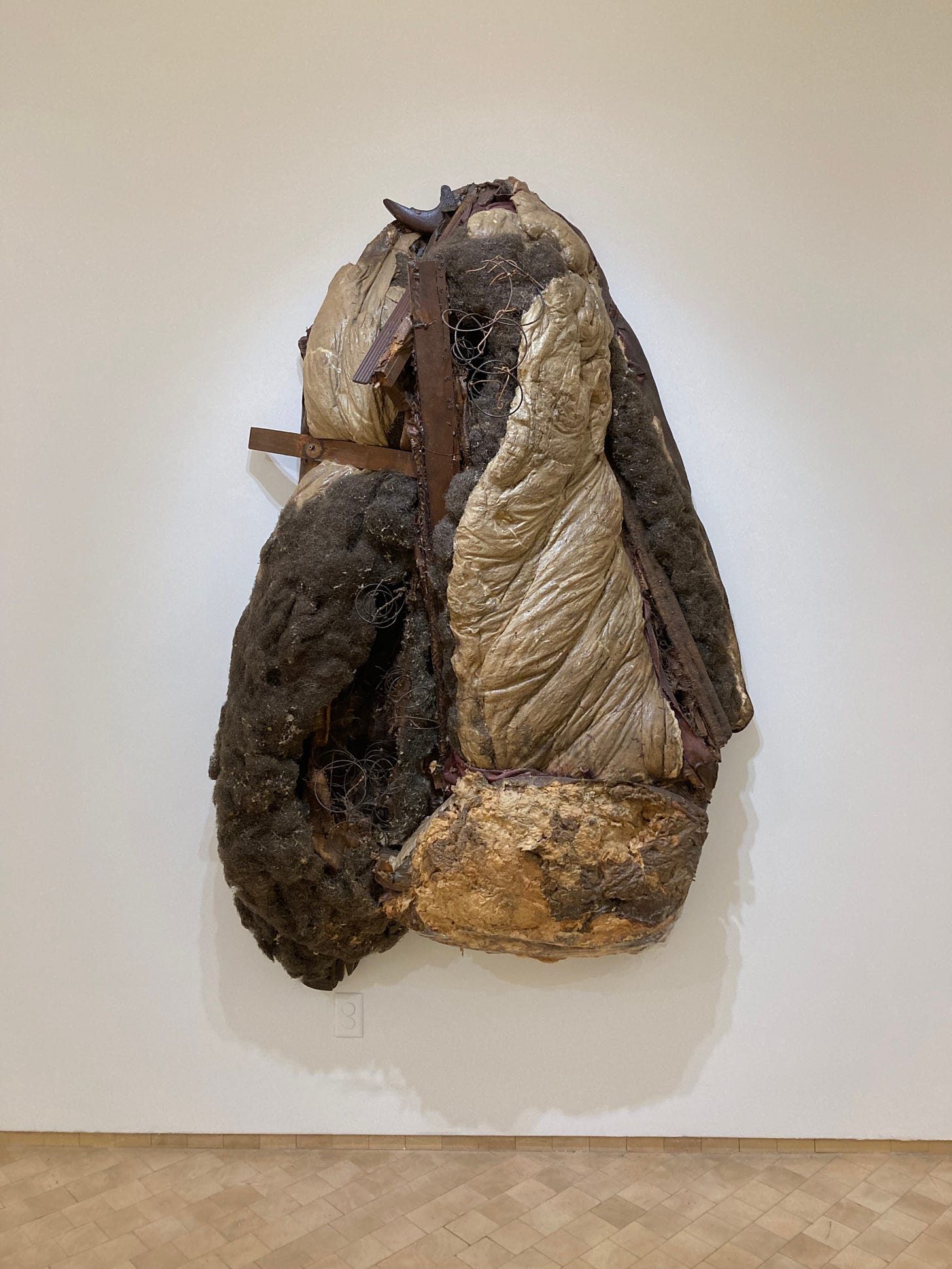

Montañez Ortiz’s antipathy to consumption and familiar forms of essentialism most prominently took the form of hacking furniture with axes and setting it ablaze to create ugly, compelling, guts-inside-out sculptures in the early to mid ’60s that he called Archeological Finds. There’s a great room of these at El Museo. He saw violence as (de)ontological shamanism. A great 1966 quote on the subject plays off the classic Western-philo trope of the chair: “Each ax swing takes me away from the chairness of the chair to the transcending complexity internal in all things. Each ax swing unmakes this made thing called upholstered chair; each destruction unmakes my made relationship to it.”

Working at his studio in Coney Island, RMO found that people would gather at his open door to watch him smash stuff up. Like demolition derbies? You’ll love Raphael Montañez Ortiz. Thus he became a performance artist, appearing at the notorious and well-mediated Destruction in Art Symposium in London in 1966, while continuing to make sculptures and cutup films. He engaged in activist street theater; he worked with groups like the Young Lords. The guy even founded a fucking museum, El Museo del Barrio itself, which to me seems like quite a lot of work and also appropriately paradoxical for a guy who reveled in destruction as the key to psychic liberation.

Like lots of performance artists, after his heady youth, RMO realized he had better get a job. He started teaching at Rutgers in ’71 and is still on faculty today at age 87. A notable highlight of his later output on view at El Museo are the trippy “Laser Disc Scratch Videos” that he made starting in 1985 with some custom equipment made by colleagues in the engineering dept. and an early Apple computer. “I had this idea of making the computer dream,” he said in 2011. A true man for our times: both a shaman and a willing adapter of NEW TOOLS.

Like RMO’s background—and distinctly emerging from it—his philosophies about art are complex and syncretic. I’m no expert, but they draw on anthropology and meld animistic elements with Freudian ones. An iconic example is his 1966 Chicken Destruction Realization, which was not highlighted at El Museo for reasons that the title should make clear. The centrality of RMO’s identity to his work is no doubt one thing that separated him from peers like Oldenburg or Dine or even more imaginative yet ultimately characteristic types like Schneemann. If I was too oblique earlier, I have a strong hunch that racism has a lot to do with his relative obscurity: it’s a lot easier to get away with being “crazy” when you’re a Swedish aristocrat.

The exhibition at El Museo is strong with the early sculptures and the ephemera and documentation it includes. Unfortunately, for whatever reason, only one performance is shown as moving image, a piano smashup at the Whitney that I believe was in the ’80s or early ’90s. Watching RMO in his signature milieu is surprising. His demeanor is the opposite of what I expected, which was something frenzied and overtly purgative. In fact, at least here, he’s methodical as he circles the instrument, picking his spots and testing out angles. You can see internal debate unfolding. And the work is as much music as performance art: The piano wires hum and sing erratically throughout as the machine is pounded and pried at.

Props to Rodrigo Moura and Julieta Gonzalez for giving Montañez Ortiz a worthy show at the place he founded, as well as to others who have in the last decade brought RMO to new audiences: Pedro Reyes at Labor in Mexico City and Catherine Taft at LAXART in LA for doing substantial shows on RMO in 2011 and 2017, respectively.

Raphael Montañez Ortiz: A Contextual Retrospective closes at El Museo del Barrio on WTC All-Saints.

Friends and Acquaintances

Books

Move over all you rosary clutchers: the new shit is talking to your dead pets. You tradcaths chitchat with god all the time, not to mention Jesus and the Virgin and the saints and heck even the angels. Why not the ghosts of our dearly departed dogs and cats? Since coherence is passé, karmic mediumism should play well with the other cults; you can be a pro-ana mystic and still vibe with the feral spirits. Paganism, you say? You think when I’m seancing with the goldfish I just flushed, Asmodeus or Belial is going to cut in and lure me into Satan’s clutches? Am I so mentally weak? How do you know he’s not sowing his invisible seed on the host right before it touches your tongue?

I swear if I sat at the bar at Clandestino and read aloud from this beautiful book we could end this avant-papist shit once and for all. Get yourself a copy before Dasha puts a fatwa on Saint Penelope’s head.

Wine

Agnès et René Mosse Vin de France Bangarang 3eme Mise Rosé 2020. I was at the suave and stylish newly renovated downtown bachelor digs of a friend of mine, debating the fine points of NFT collecting, the artist-streetwear brand collabs we’re most looking forward to for spring 2023, and the latest news about famous Norwegian hip hop collective Drain Gong when he produced a bottle of this ridiculously named rosé and popped it open. It’s actually delicious. It’s from the Loire but starts out tasting like seaweed, which sounds gross but quite the contrary. As you drink that fuzz wafts off, leaving you with the tang of a mountain spring, a fashionably distressed watermelon jolly rancher, and a hint of the hard and ductile transition metal nickel. Bangarang!

Music

Recently I found myself listening to Drake. I had intended to listen to Drakeo the Ruler, who was fucking great and was horribly stabbed to death last December. But then Spotify autofill threw up the image of Canada’s toughest hip-hop soldier. Drake has always been corny, which was his charm; a nerd playing a cool guy and pulling it off sometimes—like, “Fuck physics, the bumblebee can actually fly.” I wondered if he had matured on the new record. Not really.

I find Drake effectively melancholic until he tries to get macho, at which point he becomes either ridiculous or obnoxious, like a 12-year-old boy who’s trying out the dirty words he just learned for parts of the female anatomy. And issues of appropriation aside, the coding of house music hardly butches him up. I wonder if he knows he’s queering himself.

Anyway here’s some Drakeo. RIP. I might write more about him next week.