Nothing to Do but Cook

Listening to Clipse in Tuscany. Plus Swiss white wine and a movie I absolutely hated.

Greetings from Siena. Thus far, away from the maniac rhythms of New York, I’m finding it paradoxically hard to concentrate. It’s a slow place I’m staying in, two dozen sleepy cats dotting a dozen little streets and alleys, and my thoughts tend to diffuse quickly. The scenery is stupefying. I’ve spent a lot of time being jetlagged and looking out the window, struggling with these new Euro screwtops (you can read more on that subject from Big Bottlecap here). Otherwise I’ve read a little Chantal Mouffe, watched a few bad movies, and decided to dial down my NDRI dosage from NYC levels to something suitable for the contemplative countryside.

Wine

Hope you all enjoyed Basel. I’ve never been, not to the fair anyway; once during some postcollegiate tramping around, I passed a couple hours there. The only thing I did was visit the Tinguely Fountain, and I was not impressed.

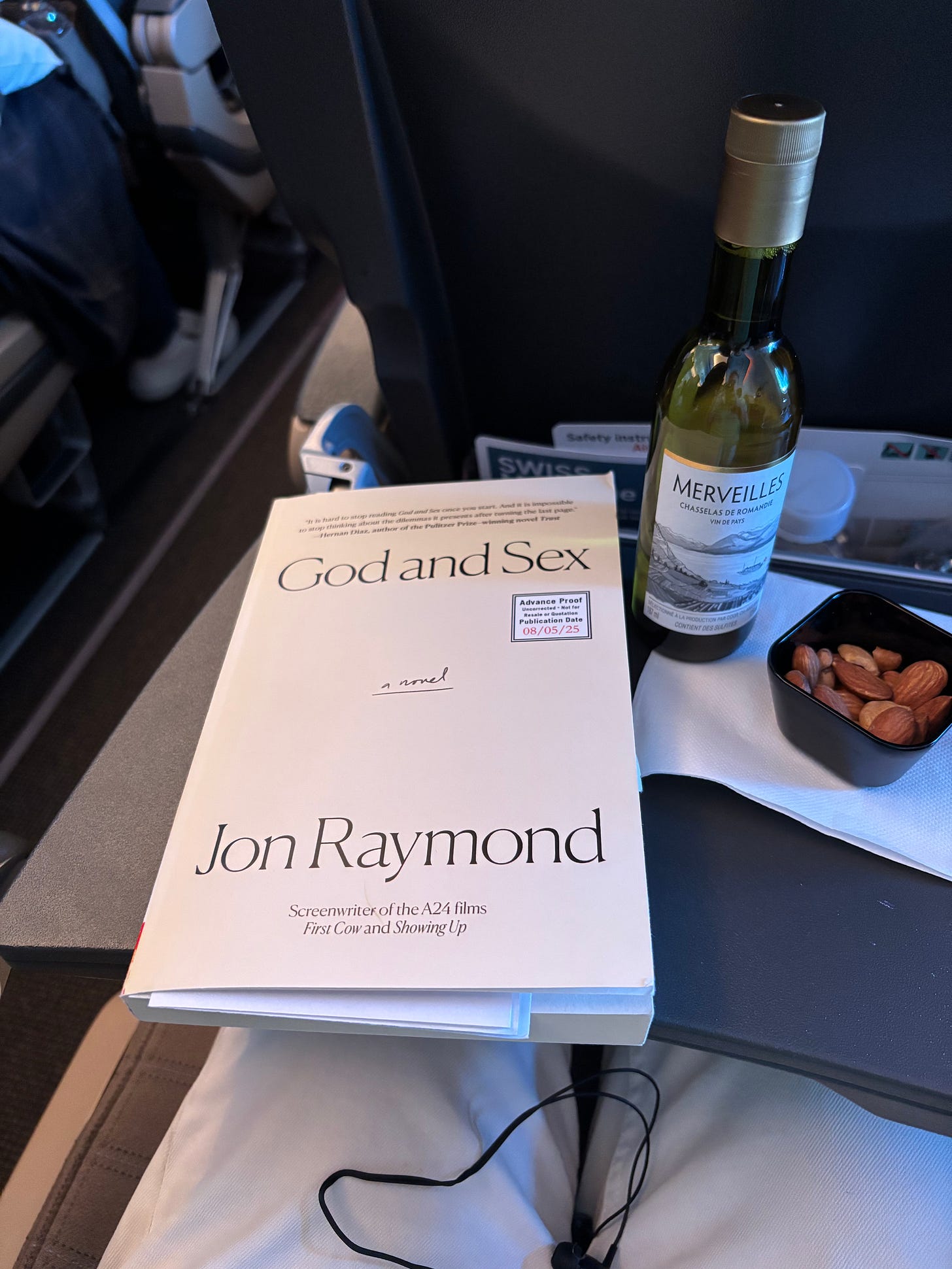

While I’ve missed out on the Jordan Wolfson Freaky Friday experience (let me know how it was), and I still don’t really understand what the Basel Social Club is, I did get a taste of Switzerland—literally—when I flew Swiss Air on my recent transatlantic flight. It afforded me the opportunity to drink some Chasselas, which generally isn’t so easy.

Chasselas is the most common white wine in Switzerland, but CH isn’t exactly a wine-exporting country; around 98 percent is consumed domestically. The first time I had it was after an Alexandra Bachsetzis performance at Pioneer Works, when the local consulate pulled some out of their vault for the reception. It was crisp and delicious, a lot like the whites I’m typically hyping.

The version served by Swiss Air called itself, unabashedly, Merveilles. It had the slightest nose of squeeze-bottle lemon, the first taste of a matchstick spark—a poor-man’s Pouilly-Fumé, thus. It progressed in that vein, like a sauvignon blanc but less grassy, into a little rounder aspect with some bitter vanilla, like the extract you surely tried, like me, to drink as a kid. It bottoms out in a way that gets a little tarry under the brightness, but it leaves a little sparkle on the tongue if aerated properly. It’s a fine way to be middling, which is kind of what you’d expect for the coach-class wine on Swiss Air. I’m sure I’ll drink a bottle on the flight back in August.

Film

Did you love Asif Kapadia’s brilliant documentaries Senna and Amy? Then you’ll hate his most recent movie, 2073.

2073 came out last December 27, a release date that was kind of a burial. The film didn’t get much press; I’d never heard of it until this week. It turns out to be one of the worst movies I’ve ever seen, especially by an accomplished filmmaker. 2073 combines hamfisted dystopian sci fi with, essentially, a documentary about how the contemporary rising tide of authoritarian populism is converging with the grotesque desires of techno elites to endanger democracy. There’s nothing wrong with that story, except that anyone who has spent more than five minutes alive in the last decade has already heard it ad nauseum. Making myself sit through the whole thing provoked my own personal crisis of criticism.

As you may recall, Senna and Amy are rigorously constructed through period footage of their respective subjects—which makes it jaw-dropping when, in 2073, Kapadia relies in the docu-side of the feature on studio talking heads and voiceovers. They’re interspersed and laid across undeniably bleak footage of extralegal murder by the authorities, marching Nazis, climate catastrophe, and so on. The by-the-numbers presentation drains aways whatever innate power to disturb it might have, however. Likewise the presentation of Blue Origin rocket landings, corporate logos, and grinning, ghoulish CEOs.

Yet more strangely, Kapadia extends the use of voiceover throughout the fiction parts of the film, a function of his choice to make the protagonist, named Ghost, mute. VO is notoriously the refuge of a director who can’t manifest their story via acting, dialogue, editing, photography: the basics of cinema. Thus it’s bizarre that Kapadia made a decision to drive his movie straight into hack territory. Without Ghost’s internal monologue, we’d have no access to her thoughts. But do we need them? The story in the film could not be more obvious, the images never subtle. The movie would have been just as clear—and at least a little better—with no dialogue in the fiction section at all.

The entire 2073 viewing experience makes it seem as if Kapadia and his co-author only had time to cook up a monologue instead of a full-scale script and barely revised it. The rote explication of the film’s dystopia by the unfortunate Ghost (played by an even more unfortunate Samantha Morton) mobilizes every cliché imaginable, including excruciatingly wistful references to the protagonist’s spunky grandma. One amazingly libbed-out scene manages to hash together the appearance of a kindly Black character bearing herbal tea and wisdom for our white protagonist with the film’s only use of ASL and inexplicable girl-power pink cursive subtitles.

Logical holes abound in 2073, which is ironic for a film that so desperately wants to root itself in “the real.” Ghost lives with other lumpenproles in the sub-sub-sub-basement of an abandoned shopping center in New San Francisco. (When the apocalypse comes to New York, I’m holing up at the similarly designed FiDi Alamo Drafthouse). She emerges furtively to dumpster-dive for food and other supplies, but who is doing the dumping is unclear, since we see virtually no society aboveground at all. There are some heavily armed cops—and the only genuinely sinister element of the movie, surveillance drones—as well as a handful of elites visible in two quick shots, one in an office containing priceless artworks and the other at a lavish dinner. Where, then, did that copy of The Autobiography of Malcolm X come from, the one that Ghost finds? Somehow such crimethink escaped liquidation by the powers that be and otherwise survived the 37 years since “the event” that upended everything. Kapadia’s use of preexisting footage in the sci fi portion of the film leaves other gaps. A woman is seen rooting through a garbage bag of discarded fried chicken. Who is supposed to have left behind the fresh scraps?

The greatest mystery of all, however, is how 2073 ended up so bad. I can only imagine that, like many of us, Kapadia perceives the gravity of the situation we’re living in, and he felt he had to do something, to speak out using the means at his disposal—and fast. That’s the only explanation why someone with such command of filmic tools has wielded them in such a slipshod, half-baked, counterproductive way here.

Music

The PR campaign for Clipse’s upcoming album has been expertly executed, an incitement to what everyone hopes is the next great rap beef, between the duo and Travis Scott. Clipse’s Pusha T is famously sharp as a lyricist and, not unrelatedly, famously ruthless when it comes to a diss. Naturally I’m an admirer of his work, even if I’m not blown away by the new track in question, “So Be It.” For a better sense of the group’s abilities, in the coke-rap narrative mode, I present 2006’s “Chinese New Year,” which also features the brilliantly named Roscoe P. Goldchain (the band and I do have generational affinities) and the quirky boom-bap production of Neptunes-era Pharrell, years before anyone might have imagined he’d head up menswear at Louis Vuitton.