Queen Bitch

Ravi Jackson, Richard Maxwell, and dance in cinema. Plus a oenological Michel Foucault mystery

For weeks now, the weather in New York has been frightful, in the horror-movie sense: gray, damp, and snowless skies have turned the city into a sepulcher for a month. Mercury has been in retrograde, I misplaced my Adderall cache. So thank you, dear reader, for your patience during Spigot’s heretofore Dry January.

Art

The Ravi Jackson show at David Lewis presents a number of wall-based paintings/photocollages on the walls and vaguely architectural sculptures around the room; there’s even a desk in one corner with a hand-stitched poof on top. The awkward stylings are (Rachel) Harrisonian, with patchy and brisk coloration where paint has been applied and an aggressively fuckall affect. Jackson has also plopped some oddly disconcerting fat wax objects on the floor, roughly rectilinear volumes like misshapen bricks in sickly color blends—plus the occasional pooplike cone. At the opening these all were in obvious peril; I appreciated the laissez-faire.

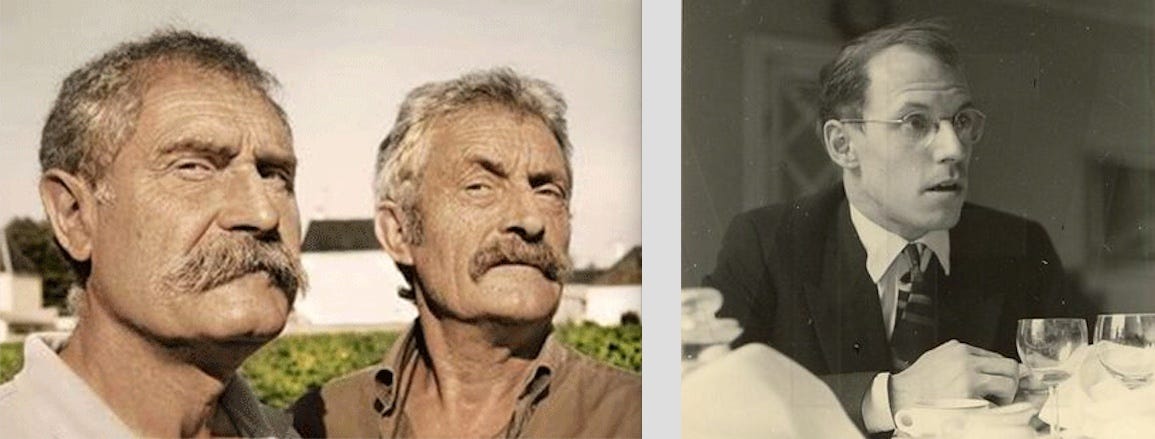

Jackson’s show is titled Hardcore, and the focal point of the imagery is Lil Kim, in re: her album from 1996. Rihanna also appears, and an oddly familiar, comically mustachioed white guy in a Western movie who turns out to be Kurt Russell. Other pictures are anonymous and sexual: a sliced-up bodybuilder, a provocatively gaping mouth, an eye, an odalisque. A number of the wall pieces have clunky, quarter-size panels branching off their sides, which the press release describes as a reference to altarpieces, decidedly arch for something so desultory.

Amid a collection of objects so dedicatedly material and devotedly unslick, it was jarring to find that, after just a couple minutes, I felt like I was sitting in front of a computer screen. The photos frequently declare themselves to be screenshots—a lyric page for “Queen Bitch,” an auction page for a Dick Gregory poster. A handwritten mimeograph shouting FUCK FOR PEACE! bears the gray frame and zoom options of some PDF viewer. Pictures of celebrities inevitably conjure the feed, just as turgid bodies inevitably invoke porn.

The original of the FUCK FOR PEACE! is a flier by Tuli Kuperferberg flier, a blast from the past doubles the ’60s reference made via Gregory, the lifelong activist and civil rights icon who also happened to be a ruthless satirist. The juxtaposition of these characters with Lil Kim (a historical figure herself at this point) et al. gives the show its alchemy, making its subject life online. The aggregation of all our searches is the endless search for ourselves. Identity is profuse, it piles on in unexpected and undesired ways; we all receive signals of what’s expected of us, we’re all attracted in directions that are sometimes predictable, other times not. The Gregory item for sale is a mock WANTED poster, except it says NEEDED instead.

When seeking takes place on the internet, it subsumes horniness and collides with commerce. To me, Jackson’s weird wax bricks look a lot like ugly versions of the scent-bearing candles that so many aspirational types acquire to furnish their generic apartments. One Mattel-logoed Lil Kim shot seems to be hawking her as a Barbie doll. Jackson’s flat presentation creates a degree of genderfuck: you have no idea whether he wants to have sex with Kim or be her, screw the bodybuilder or become hypermasculine—or all of the above. The accumulation of wants and identifications ends up feeling like the results of late-night online shopping binge. Like homely housewares and a lot of other crap we buy, the jumbled elements of ourselves, whether hypothetical or actualized, end up either forgotten or underfoot. If you’re lucky you can sift the NEED from the WANT and end up with Dick Gregory on your bedroom wall—if you can bid enough.

Theater

Richard Maxwell’s new play Field of Mars premiered January 19 at NYU’s Skirball Center. Advance info was scant. When its author was approached for comment by this publication, he replied, “Spigot? Lol what’s that? Go Buffalo!”

Maxwell can be hard to describe—cerebral, funny, expansive, unafraid of big themes but approaching them in disjunct ways. The 2021 play The Vessel, for example, is made up entirely of highly personal monologues on death and loss. It was written by individual members of the cast and other members of the Incoming Theater Division of Maxwell’s troupe, the New York City Players. But it’s never the author of the monologue who performed it, always someone else: the emotions were displaced from the person to whom they “belonged.” On the other hand, Maxwell began his career with drily comic, ultrabanal works scoured with the bleakness of the American workplace—but he also wrote a trilogy riffing on the Divine Comedy, culminating in 2018’s postapocalyptic Paradiso, which featured an authorial robot emcee.

Field of Mars is an eccentric panorama taking place on one of Maxwell’s characteristically spare sets, a skeletal array of booths and tables that represents both an Applebee’s in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and the cosmos. It invokes Adam and Eve and our puny species’s evolution, but these cosmic flows are channeled through a chain restaurant where the manager can’t figure out how to work the new app that runs the sound system.

Sparks fly off in myriad directions: the second act, for example, begins with a moment of direct address by an actor detailing a period of homelessness, reflections on nihilism versus hope. Is it autobiographical? How does that uncertainty color what we’ve seen thus far, and how we see what comes after? The title Field of Mars gestures toward the violent, and the play doesn’t shirk conflict, be it among Neanderthals hilariously murdering and fucking each other or an intergenerational group of music bros in a corner booth conducting the most maddening aesthetic argument imaginable.

All of which makes Field of Mars my favorite of the four or five of Maxwell’s plays I’ve seen. His plays have riddling aspects, but he’s never arch; he never puts you on. Rather he invites you to work alongside his oblique, philosophical, crass, and humane sensibility on a puzzle with no solution.

Wine

Clos Rougeard Saumur Champigny 2015. The story came to me a few years ago, in an email from one of those proliferating natural wine shops that are suffocating Brooklyn like algae on a pond. Somehow the place had acquired a couple cases from the last vintages of a legendary pair of brothers, one elderly and one deceased, who were the ninth and last generation of their family to run the famous Clos Rougeard vineyard, nestled alongside the Loire. Their name: Les Frères Foucault.

I had never heard of Clos Rougeard, founded in 1664, or the Frères, Charly (RIP) and Nadi. But I had heard a great deal about the renegade scion of L’Ecole Normale Supérieure who had done so much to revolutionize postwar thought. Research revealed that Michel was from Poitiers, a tantalizing ninety-minute drive south of the winery. His great-grandfather was named Jacques Symphorien Foucault—and Symphorien is a commune ninety minutes on the other side of Clos Rougeard. This Jacques was born in Angers, a mere 55 km from Clos. And so on

After a while I got bored with this research: putting genealogy and Foucault together in a search field gives you an awful lot of results to sift through, and until I win a Warhol grant, I’m not paying for a subscription to MyHeritage.com. Also these Foucault Bros. have generated barriques of prose themselves, one hagiography after the other calling them “mysterious” and “mythic.” High-end wine writing brims with sentences like this: “But if Clos Rougeard is the DRC of Cabernet Franc, Collier is the Coche of Chenin Blanc.” My skills as an art critic may really be transferrable after all.

Satisfied that Michel, Charly, and Nadi were cousins of some remove, and flush with Biden bucks, I ordered a bottle of 2015 Samur Champigny. Paul Preciado was unavailable, so instead I split it with an old friend from Staten Island.

We opened it Saturday night. The cork broke.

For a decanter, we used a little Greek pitcher I found on the street; for glasses, the stemware I had found outside a Polish lady’s house. The first sip tasted like rocks, no surprise. And so we waited. We blew a bunch more money on saucisson sec and goat cheese impregnated with fennel pollen and duck breasts I miraculously did not overcook, so we passed the time gorging ourselves and watching the Foucault-Chomsky debate.

One hour in: nothing. Two hours: not much.

We switched from Dutch television to Death Grips and discussing I, Pierre Riviere.

Though neither of us would admit it, by hour four we both had given up hope. And then, perversely, the wine finally did transform. At midnight, like an inverse Cinderella’s pumpkin, the texture improbably lightened to that of a Beaujolais, the fruit materialized sweetly, the tannins dropping and rounding. It was a shock. It tasted almost like candy.

Film or Dance or Music

I’ve been so depressed lately that I haven’t been listening to music. I have, however, been watching dance sequences from movies.

This turn of events, unexpected for someone who loathes musicals, was prompted by a trip to see Il Conformista. As a work of art, it’s hard to argue with, though it’s also a little cinematic for my tastes—so many symbols and visuals and scenes of import. On the other hand, it has the best dance sequence this side of Climax:

Though I hate dancing myself—it always feels compulsory—I found that watching it brought a little joy to the depths of winter. Naturally the next dance scene I went to was that Claire Denis, you know the one. But because I hate spoilers, I’m omitting it here, offering no hints as to the film. The Pulp Fiction scene turns out to be less extraordinary than I remembered, relying as it did so much on the Travolta meta-narrative and the crackling surprise of the film’s pacing to one unfamiliar with the French New Wave. Also Mia and Vincent suck at dancing. Take another look for yourself and restore the shock of the new, if you haven’t seen it in a while.

But the number that had somehow lodged in my skull was the father-daughter rehearsal scene in All That Jazz. If you don’t know the film, see it ASAP—it’s a fantastic autobiographical self-laceration / phantasmagoria by Bob Fosse. There’s a famously horny full-troupe routine that the choreographer protagonist stages for some producers, with a degree of self-parody that has remained oblique to me on multiple viewings.

Most potent for me, however, is a brief rehearsal between the Fosse surrogate and his daughter. It’s very sweet and yet overly intimate: there’s something undeniably odd about him and his tween daughter running through a sequence of highly gendered, almost-but-not-quite sexual poses. Meanwhile, though, they’re just chatting. The kid takes the emotional intimacy too far, interrogating her dad with a sharply wielded innocence about his various romantic affairs. (“What about the blonde?” “What blonde?” “The one in Philadelphia, with the TV show.”) The physical relationship is chaste, athletic, and precise; the emotional one seems a lot more messy.