The Invisible Dragoon

Wade Guyton, Vivian Suter, and not seeing the Eras movie. Plus being over art being "over" and a live Dave Hickey event

Dispiriting times; it’s hard to think much about art. I had a fever for a few days and spent a week alone in my apartment menaced by my phone and laptop screens. I’m claustrophobic to begin with, and the whole experience left me feeling hemmed in. I didn’t even drink, which is why there’s no wine in this week’s Spigot—sorry! If you find any typos, blame sobriety.

Last weekend I did have a laugh, however, when I discovered that the New York Times’s Jason Farago had rake-stepped into one of the more tedious running conversations of the past several years: Is art over? Farago is someone I respect, so I was surprised to see him get involved with the subject. It’s a Donnie Darko level question, whereas good criticism is of course only ever produced under the banner of Southland Tales.

To be fair, Farago does give the fool’s errand of disambiguating the new and the good a solid go. The precise question he takes up—to the length of five thousand words—is “What happens to a culture when it loses . . . velocity, or even slows to a halt?” His answer is that what artists produce simply becomes a recombination of every accessible previous form.

If you are remotely familiar with the notion of postmodernism, this conclusion is more or less indistinguishable from the one arrived at by its theorists in the 1980s. Farago allows this point, as he must. It’s one example of how, when people take up these interlocking questions of art’s dead end, they invariably have to caveat themselves to death to avoid seeming ridiculous. Well of course some new things are being made today; of course not everything is terrible; why, I even like some of it myself!

Therein lies a clue to why people can’t quit the “Has art stopped moving forward?” discourse-industrial complex. The key figure in Farago’s musings is, of all people, Amy Winehouse. In his attentive examination of her music, he carefully traces her sources and points out how her work differs from the originals, with the conclusion that her pastiche transcends the tired old postmodernist kind of pastiche. But he fails to persuasively articulate how it does. It just does! She’s just better.

And that’s what arguments about why art fails to innovate always really are: ways to backdoor the proclamation of your own standard of value. You might as well abandon the whole kinked-up charade of the new, the modern, and the timely and just talk about what you really want to talk about: your own idea of what’s good.

Art

I did spend some time in recent days trying to remember what I once knew about Wittgenstein, and failing. I don’t know how I ever thought I knew anything about his thinking at all—a sentence Wittgenstein himself would have had a good deal of fun with.

But Wittgenstein’s idea of language-games—roughly speaking, the social conventions and practices in which language is used—always comes to me when writers get tangled up in the insoluble question of why culture has come to a standstill. They don’t understand what game they’re playing. Likewise he came to mind this week thinking about how artists move their work from the context of its making into the gallery, and how well they do or don’t know the rules of the game they’re playing.

Vivian Suter has lived and worked in the Guatemalan jungle for decades, making broad, bright paintings on unstretched canvases that she works on both out- and indoors, matter-of-factly integrating them with their environs as they accrete dirt and twigs. I first became aware of Suter in 2016–17 when she created work on the still-sulfurous volcanic Greek island of Nisyros, a burned-out caldera whose center is soft and warm to the touch. She showed the results in Athens during Documenta 14 flapping freely in an open-air pavilion at an old Orthodox church on Filoppapou HIll.

With this Suter in my head, I’ve had a hard time reconciling myself to seeing her work in a white cube—like at Gladstone 94 in New York right now. I feel like the work itself balks as well. Curators take various approaches, sometimes hanging it in rack-like arrays, others in ways that resemble interior architecture. Though they can create a kind of surround, the arrangements are always very planar. At Gladstone, you enter the show via stairwell into a room like a hallway, making the strongest single impression of the experience that of her paintings crowded against one wall and converted into a stiff visual patchwork.

I’m always surprised Suter keeps things so rectilinear in these circumstances. Just once I would like her to make an atmosphere of her paintings, where to pass through you had to brush past and between them like drapery. Is that corny? Maybe. But her canvases hanging free and unstretched in a rainforest or on a mountaintop is one thing; hanging so in a New York gallery is an uncomfortable nonchalance. At Gladstone’s townhouse on the Upper East Side, a balcony is right there on the other side of a big window. Couldn’t we drag a few out there and see how they fend with the elements here in New York?

Wade Guyton’s installation at Matthew Marks, by contrast, is more than attuned to its conditions, dealing with the idea of the showroom, real estate, and the ghosts of the loft economy. Entering the gallery, you’re confronted with a 3D grid, a matrix, a grammar on which most of the paintings hang. This metal rack system conjures streetside scaffolding; in fact Guyton scavenged it from a clothing company that left it behind when he moved into his current studio. He uses the racks for storage, so moving them into Marks extends his interest in bringing the studio into the gallery so visible in his paintings in recent years.

The effect in this case is part warehouse: get your Guytons here, wholesale! This devaluation of the preciousness of the individual artwork is something the artist has long played with. At the same time, in the dim light, there’s a melancholy about the install, also not entirely new for him. It feels a little funereal, the paintings more than clothier’s samples, pinned like specimens, his signature Xs like moths’ wings, against this (outmoded) modernist gridding in three dimensions.

Public Relations

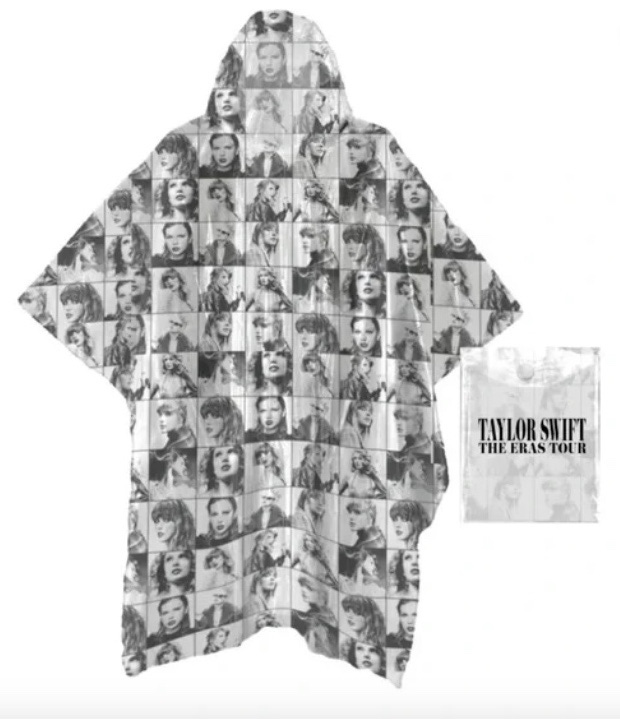

More than one person has asked me in the past week or two if I was excited to see the Eras movie. No, I am not. The thought of buying a ticket to it makes me feel sad and broke.

The cheapest ticket I could find for Swift’s MetLife gigs was in excess of $600 for the worst seats in the house. If you felt left out of the religious ecstasy induced at football stadiums around the country this summer because you weren’t willing to rob a casino, being offered a pale imitation of the experience for the low low price of movie ticket stings. It’s like Plato’s Cave. I too want the real thing, not the flickering shadows!

While I have also been enervated by Swift’s full-spectrum dominance of the American infosphere, I also can’t deny that I admire the Travis Kelce campaign, her exquisitely timed romance with the best receiving tight end in football history who also cohosts one of the nation’s most popular sports podcasts and happens to be a recently microchipped Big Pharma shill. Her dalliance with the colossus that is the NFL occurs—no doubt by sheer coincidence—just as the Eras tour movie hit screens ten days ago, with her the drop of her 1989 rerecord slated for this Friday. Let’s not lie to ourselves: has amour fou ever worked for you?

I do enjoy imagining the pitch meeting at TAS Rights Management LLC, wherein months of NSA-level research on handsome, eligible American football players was distilled into a fifteen-minute multimedia presentation featuring game footage, talking-head testimonials from elementary-school teachers, infographics, cost-benefit analyses, and an appearance via Zoom by Al Michaels discussing the Chiefs’ odds to win the Super Bowl this year, all to sell Swift on a liaison that would give her a breakthrough entrée to one of the few demographics she has yet to conquer: straight middle-aged men.

A breathless pause. Taylor nods. Corner offices for all involved.

My over/under on a breakup date is mid-November. Two-thirds of the way through the NFL season, Swift will vanish from the luxury boxes and the pair will release a joint statement explaining that they’re amiably spending some time apart while Travis focuses on the Chiefs’ stretch run. No doubt she’ll turn back up when the playoffs start, but given how blasé KC looks this season, don’t expect to see her at the Super Bowl.

Music

Enjoy the Eras movie. Really. I’ll see it one day, or next week. In the meantime, I’ll be listening to this mashup of “You Need to Calm Down” and “Paper Planes,” a crosshatching of hamfisted liberal pieties and radical chic. At the moment, I keep hearing bits that the cleverly pseudo-anagrammatic Kyle-E_Wyote left out, the gunshots and the cash register cha-chings.

Spigot Live!

Dave Hickey and The Invisible Dragon 30th Anniversary Edition Book Launch

Tuesday, October 23

6:30 pm

McNally Jackson SoHo

RSVP

I’m very pleased to be taking part in the launch event for the new, expanded, thirtieth-anniversary edition of Dave Hickey’s The Invisible Dragon this Tuesday. Thank you to Stephanie LaCava and Gary Kornblau for the invitation. I’m flattered to be part of a great lineup: Felix Bernstein and Gabe Rubin, LaCava, myself and Paige K. Bradley, and Christopher Bollen, plus music by Laura Ortman, who wrote songs with Hickey in recent years.

Air Guitar was the first book of art criticism I discovered. I found its author a little overattached to fusty ideas like beauty—which happens to be the subject of The Invisible Dragon—as well as, horrors!, America. But his heart was in the right place, and I agreed with him on a lot of fundamentals. Moreover, he could charm me into believing just about anything. To express it in a vernacular he might have appreciated, he could write like a motherfucker.

Air Guitar ended up being an important influence on my criticism, not through aspiration but affirmation. Hickey showed me that you could write persuasively—seductively, even—about art with flair and without pretense, and that it was possible to do so brilliantly.