The Last Word on Normcore

An essay on tempo and trends, forecasts and psyops, self-awareness and hype cycles. Plus lamestains and cob nobblers.

Yeah, I know. Who cares, right?

But I’m slow. Late to the party slow, late to my own funeral. Working at a snail’s pace is a handicap when it comes to putting out a regular newsletter. (Apologies, dear reader.) Sometimes I have to pretend that procrastination is a good thing, as if something in me is waiting for inspiration to descend, a decisive moment to arrive.

We’re a long way from the age of Henri Cartier-Bresson and gelatin silver prints, however. The images that capture our attention are screengrabs from the continuous multichannel video feed of the uberconscious. They go by too fast to be decisive; or rather, the speed with which they pass us by—pass through us—is so great that they render the notion of a critical instant moot. If a moment seems decisive now, don’t worry; in a day or a week or a year it’ll be a figment of your imagination; it won’t matter at all.

Because I think a lot about the scope of history in comparison to our fleeting lives, I don’t care so much about trends. They’re disposable, marginally informative—and, crucially, fake. Birds aren’t real? Trends aren’t real. They’re factures of the media such as it exists ca. 2024, which boils down to (a) a clutch of writers for a few New York publications, and (b) the algorithms of social media. What’s trending is what’s made to trend, and it’s made to trend by asserting that it exists. In fact, the axiom goes back to the heyday of black-and-white newsprint: it was stained newsroom wretches, not the editors of The Cut, who first said, “Three examples make a trend.”

Because I am slow, I’m only getting now to writing about dueling pieces of hagiography that appeared a couple of weeks ago to mark the tenth anniversary of the rise of “normcore.” Who knew that the subject was so important as to require 30 people to reflect on it to the tune of 6000 words? It didn’t mean enough for me to be on trend in writing about the idea of trends, I suppose.

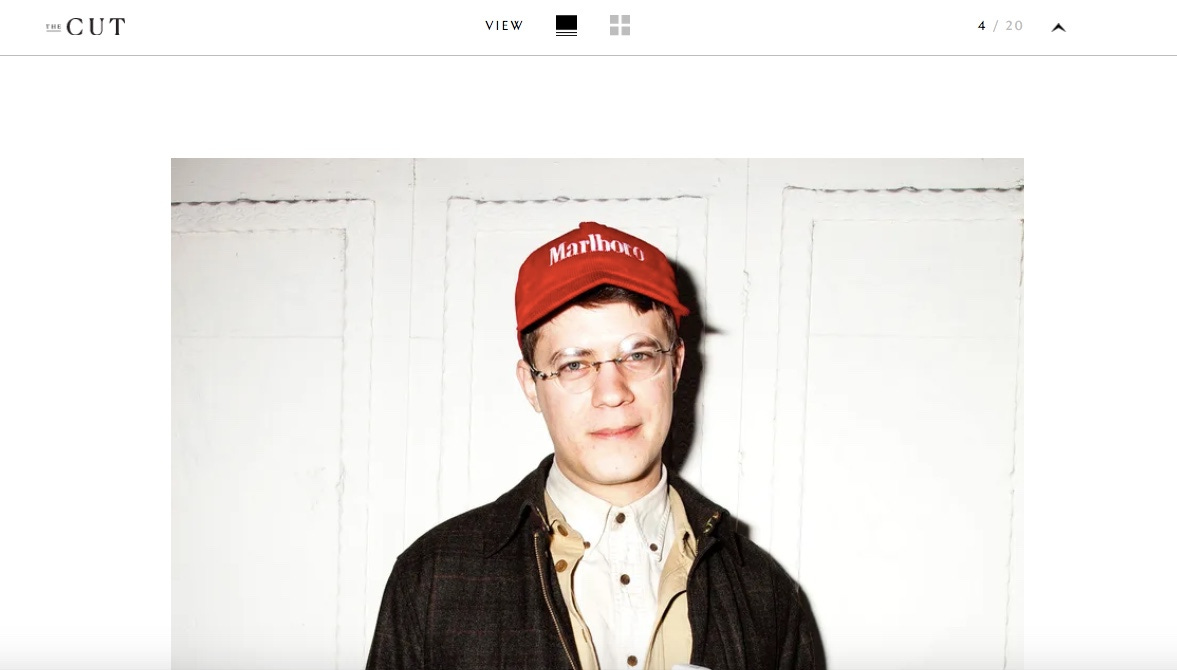

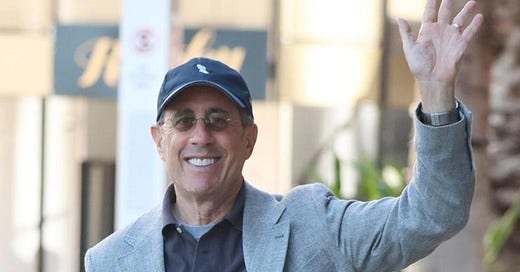

For those among my readership lucky enough not to have, like myself, shoved their head up the ass of “the discourse,” normcore appeared in 2014 when someone published a story in New York magazine taking seriously an art collective’s so-called trend report on the subject, which led to a bunch of fashion folks seizing upon and kaleidoscopically distorting the idea in order to celebrate and sell versions of the khaki pants, cheap sneakers, etc. that you expect to see when you enter a Home Depot. There was something blatantly classist about that cosplay aspect of the whole episode, which neither of the two pieces recently published addresses.

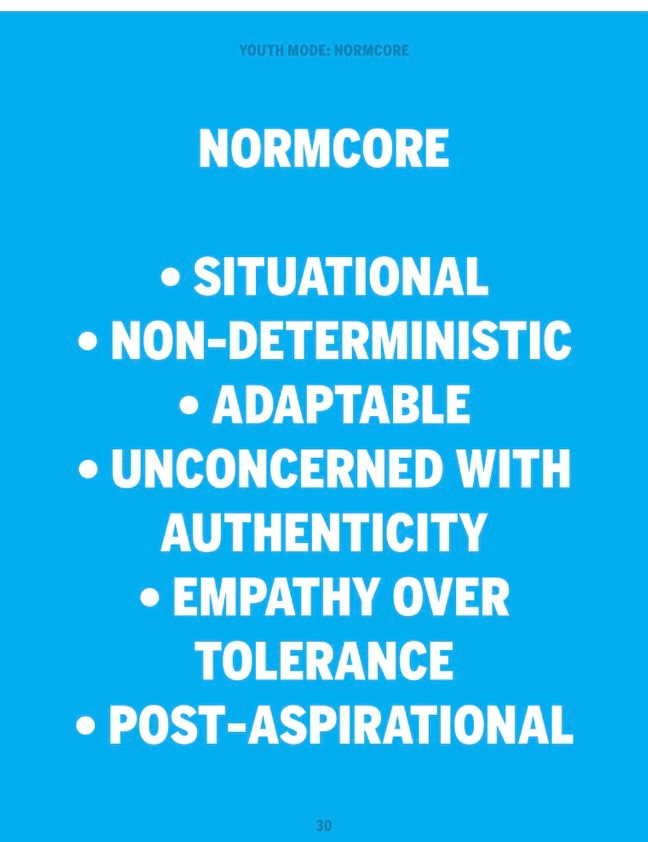

One of the articles, which appeared in SSENSE, focuses incisively on three of the principals of the collective who invented the term, K-HOLE. One of the trio, Dena Yago, explains that, in the group’s original presentation, normcore denoted giving up on individuality and instead assimilating into any given context: mutability rather than dressing like your cousin in Nebraska. “It was anti-aesthetic,” she says. “It was more about code-switching.” One of normcore’s bullet points was “post-aspirational,” and the group’s intentions seem clearly artistic: HUO was on their ass in an instant, as you can imagine.

It’s surprising, then, that the word satire is never used in the piece, since the K-HOLE conception of normcore reads so obviously as satiric—not necessarily conjured out of thin air, but hardly earnest. The author of the SSENSE piece, Delia Cai, cogently writes in her introduction, “The dividing line between naming the thing and making it a thing has never been blurrier.” Bingo. But the interview backs away from this most critical point after broaching it. Yago calls K-HOLE’s intent “cultural criticism,” and in the competing article (of which more in a moment), she refers to lancing the “farce” of generational marketing. But her compeer Emily Segal falls back on claiming insight into to the real state of affairs rather than skill with manipulating public conversation: “There are seeds of the future in the present, and there are patterns that might be weak signals now, but if you can put the pieces together, you might be able to get a sense of what’s coming.”

You might. More honestly, you’re just promulgating a notion whose truth value is irrelevant, packaging it in the most persuasive way possible, and pushing it through certain media channels. K-HOLE themselves were more or less innocently swept up in this cycle, but they appear to prefer the accomplishment not of having pranked thousands but rather having “identified” something “real.” They want to have been seers; they want to have nailed the zeitgeist. Which they did, just in a meta way. But it’s pointless to pretend your job is predicting the future when its ne plus ultra is Pantone annually decreeing the color of the year. You’re not forecasting weather, you’re seeding clouds. Clinging to this humanistic notion of trend-spotting is especially poignant in context of the algorithmic lockdown of our inclinations, data having outstripped gnosis when it comes to predicting and guiding our behavior.

The other recent normcore article was a five-thousand word “oral history.” It appeared in a publication well known for its rigorous devotion to sociological methodology and the lives of the common man—Interview magazine. The account appearing in the trend-setting outlet par excellence is a loose, back-patting tracery of the idea’s diffusion, much heavier on fashion than art. Here the K-HOLE members come across as less internally in agreement about the escapade; the third principal, Greg Fong, seems to directly contradict Yago’s pellucid explanation of the concept offered above, calling normcore instead “the desire to want to be yourself and not be pigeonholed.” The piece includes some important points about drag and gender, but mostly it goes with the flow that normcore was a real thing and is far more interested in discussing its outlines and afferents than in interrogating the mechanism by which it was effected—or what that meant. The author evinces a desire to link the “phenomenon” to the digito-surreal endeavors of so-called post-internet artists. But it’s a long way from Dis to Dockers.

Let me tell you, friends: I was in New York and very much around socially in the years leading up to 2014, and there was no contagion of people dressing “normcore.” I attended art openings, I even attended the occasional fashion party, I even went to Clandestino. Never did I walk into one of those spaces and think I was in an Applebees upstate. No doubt many of Those Who Know will sniff at my calling bullshit, but the Interview piece’s explicit incoherence on the subject is directly related to the fact that normcore wasn’t a real thing.

Normcore marked something far more important than the aesthetic of a micro-era—it marked a new trend in trend analysis and forecasting. The two recent articles recognize this—the SSENSE one is in fact good—but then swirl away. With this development, we crossed a threshold into the age of trend manufacturing (see also wishcasting, manifesting—which K-HOLE laudably addressed in their normcore follow-up). But those observing the term’s anniversary only ambivalently grasp their real import of their achievement, perhaps because they all rely on trends and fashion for their way of making a living.

With the proclamation of normcore as the sartorial law of the land, we entered an age where saying something in the media made it so. A whole grim chain reaction has ensued. Summarily we entered the era of trend as entertainment, whereby a trend matters only as a chitchat fantasia instead of having anything to do with consumer habits, individual behaviors, etc. Everyone snap your fingers for the ghost of Jean Baudrillard.

Then, with the dissemination of normcore into wider use—and its swift and, I’d argue, inevitable redefinition by those too wifty to realize that in their attempt to seize the term and reify it, clambering all over each other to seek distinction, they were making themselves objects of the very satire they misunderstood, which was about fading into the background—we entered a universe where flacks became artists, where people delect and admire marketing campaigns more than any product they might promote. And now that the language of selling has achieved high status, we confuse it with other kinds of formerly credible discourse, like commentary, critique, and art itself. The sewage has hit the water supply. With marketing so ubiquitous, we are wading eyeball deep in, essentially, lies.

The zone-flood of BS about any given phenomenon, like art, issued by someone promoting it has made commenting on that phenomenon seem dubious, hyperpositioned: if you like something you’re a stan, if you don’t you’re a hater; you always-already have some ulterior motivation for your opinion. There are far more lies flying around than earnest attempts at thinking out loud, and so all discourse is assumed to be a lie from the outset. A press release has the same truth value as what’s inscribed in an academic journal as what someone spouts on your favorite podcast. Once everything is leached of truth value, everything is meaningless. Fin.

Apologies to all my friends who work in marketing and its associated fields. I love you all. And anyway, this is all just idle conversation. I’m just saying something incendiary to get eyeballs, right? Who could blame me, regardless of whether what I’m saying is right or wrong. Words don’t sink in; they float. Blow them like bubbles. Get airborne.

Big Bag of Bloatation

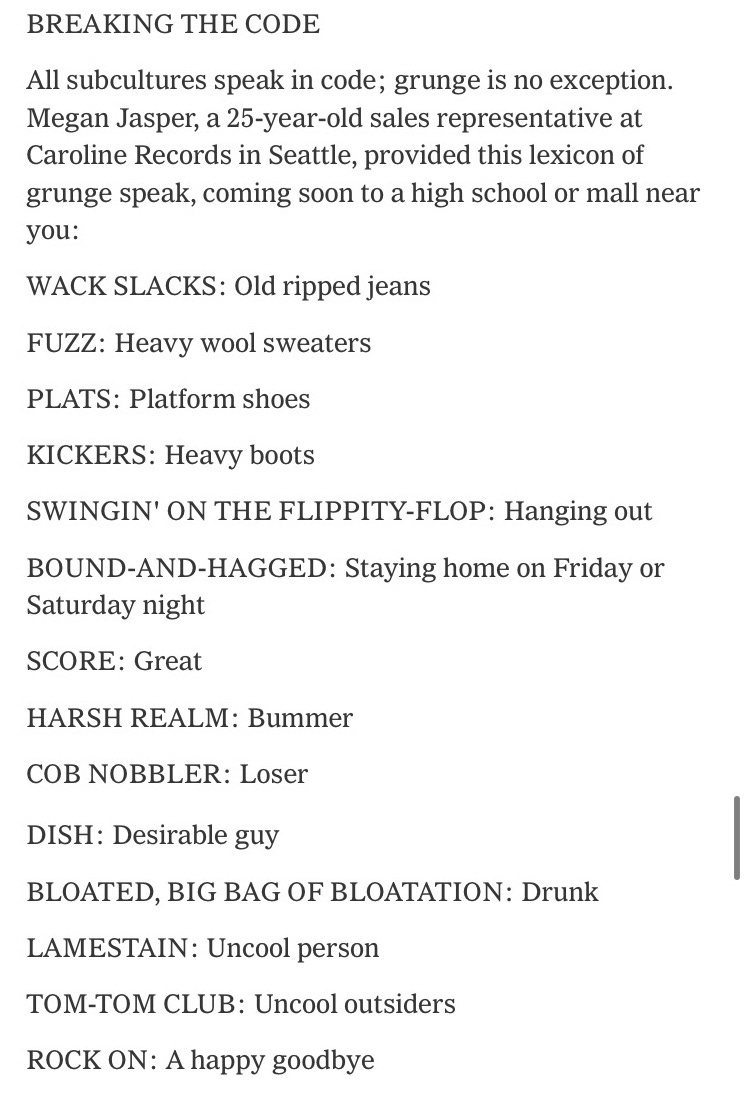

To see what the normcore phenomenon more properly was, take a trip back with me to the year 1992. An indie record-company employee named Megan Jasper fielded a call from—guess who?—a reporter for the New York Times Sunday Styles section. The resulting piece appeared under the title “Grunge: A Success Story,” with that perfectly snide citation of commerce disclosing the article’s real concern: soliciting opinions on how best to market a notional grunge aesthetic from designers from Perry Ellis and J. Crew, other journalists like the then-editor of Details, and a marketing exec. No wonder people hate the media.

The journo behind the piece had the clever idea for tagging the article a grunge glossary, a request Jasper obliged by free associating an increasingly ridiculous set of nonsense phrases, ranging from “wack slacks” (old ripped jeans) to “swingin’ on the flippity-flop” (socializing) to “cob nobbler,” the kind of person eager to take credit for starting a microtrend. A fine account of Jasper’s prank and its social context, written by Alan Siegal, may be found here.

Music

And now, in honor of an artist who appreciates great typography, enjoy the 34th most-popular song of 2014.

Was planning to just hate read this while taking a shit due to it having Normcore in the title, but enjoyed it enough to continue reading after in a chair connected to no plumbing at all. I agree with so much here. I read the original report the month it came out and interpreted it as a form of mischievous cultural engineering, but was confused by the unquestioning embracing of it that followed in the media and even my own social circles. In my daily visit to the Bedford Ave L station, it was bizarre to see people suddenly adopting elements of the report, wearing things they wouldn’t have touched prior to that while acting like they’d done it all along. And that’s not to say there was anything unprecedented going on, it did loosely follow on the existing backpack rapper style of wearing stupid boring dad shit, as well as the hipsters from a decade earlier growing mustaches and wearing wife beaters and trucker hats as they cosplay white trash while doing coke at Max Fish (admittedly this kinda describes me lol). The K-HOLE report took some withering bullshit and repackaged it without any acknowledgment of what made it so insincere and capitalistic, then pushed it through a media apparatus that’s always desperate for the next new thing, herding fashion fools into their new cage, all to reinforce K-HOLE’s own sense of self importance. I’m almost surprised to find out that it wasn’t explicitly a chaos magick spell by some contemporary discordian sect, and I really would have preferred if it was.