The Strange Case of Syd Mead and Martha Rosler

A visionary collides with a social critic on West 26th Street

The Frieze caravan is pulling up its horses this week in New York, with all the fifes and drums, the ribbons and badges, the appointments, the attendants and hangers-on. You’re too busy to read this, I know; you’re yakking yourself hoarse all over town.

These chats will regularly be punctured, however, by an aporia, in response to a simple query: “How are you doing?”

This characteristic deformation of small talk at that moment arises from our desire to say something without saying anything; to talk about it. The events, the situation. We can’t allow ourselves to talk about it because discussing politics has always been gauche; the petty concerns of real life pale in comparison to our presbetyrian thoughts of success. If we turn our backs, maybe it will just go away. Talk isn’t a crowbar. So you might as well shut the fuck up.

These observations are practically cliché, I realize. This hopefully less: that talk does do something nevertheless. It’s glue. We’ve overlaid the perceived logic of social media, that posting about some outrage doesn’t do anything to change it, onto IRL conversation. But there is the fact of camaraderie, a little communion, a defeat of being alone.

So then, should we tune in or tune out, look at the horror around us or look away to the stars?

Martha

Fate has materialized this very question with a perverse pairing of exhibitions next door to each other on 26th Street in Chelsea. Side by side, you can see the present-turned-past slammed up against the future, actualité versus fantasy, seamy photomontage against lush gouache, a social critic pitted against an imagineer.

I am referring to the chance pairing of Martha Rosler at Galerie Lelong & Co. and Syd Mead in the adjacent old Mitchell-Innes & Nash space. You may be forgiven for not knowing about either show. In Rosler’s case, I suspect it’s because few artists seem more out of step with the times, in Mead because he’s a sci fi illustrator and concept designer. But I’m a bit of a nerd, and remember Mead fondly from books of sci fi illustration I had as a kid. The two artists’ moments of reappreciation—Rosler’s in the Bush Era and Mead’s perhaps beginning now—fall on either side of the 21st century’s blackpill divide.

Rosler’s show at Lelong & Co., up through May 10, is tendentiously called Truth is/is not. The exhibition begins with an half-charming, half-flat-footed gambit. Upon entry, the visitor confronts a turnstile like from an old subway, and it’s operative: To enter, one must pay 25¢. (There’s a change machine, and a fishbowl half full with quarters so that one may enter gratis.) You have another option, however. To the right is installed a monitor and Xbox upon which you can play the game Dance Central for the cost of $1. Not being a huge dancer, nor a fan of heavy-handed divisions between art and entertainment or whatever is going on there, I dropped a coin into the slot.

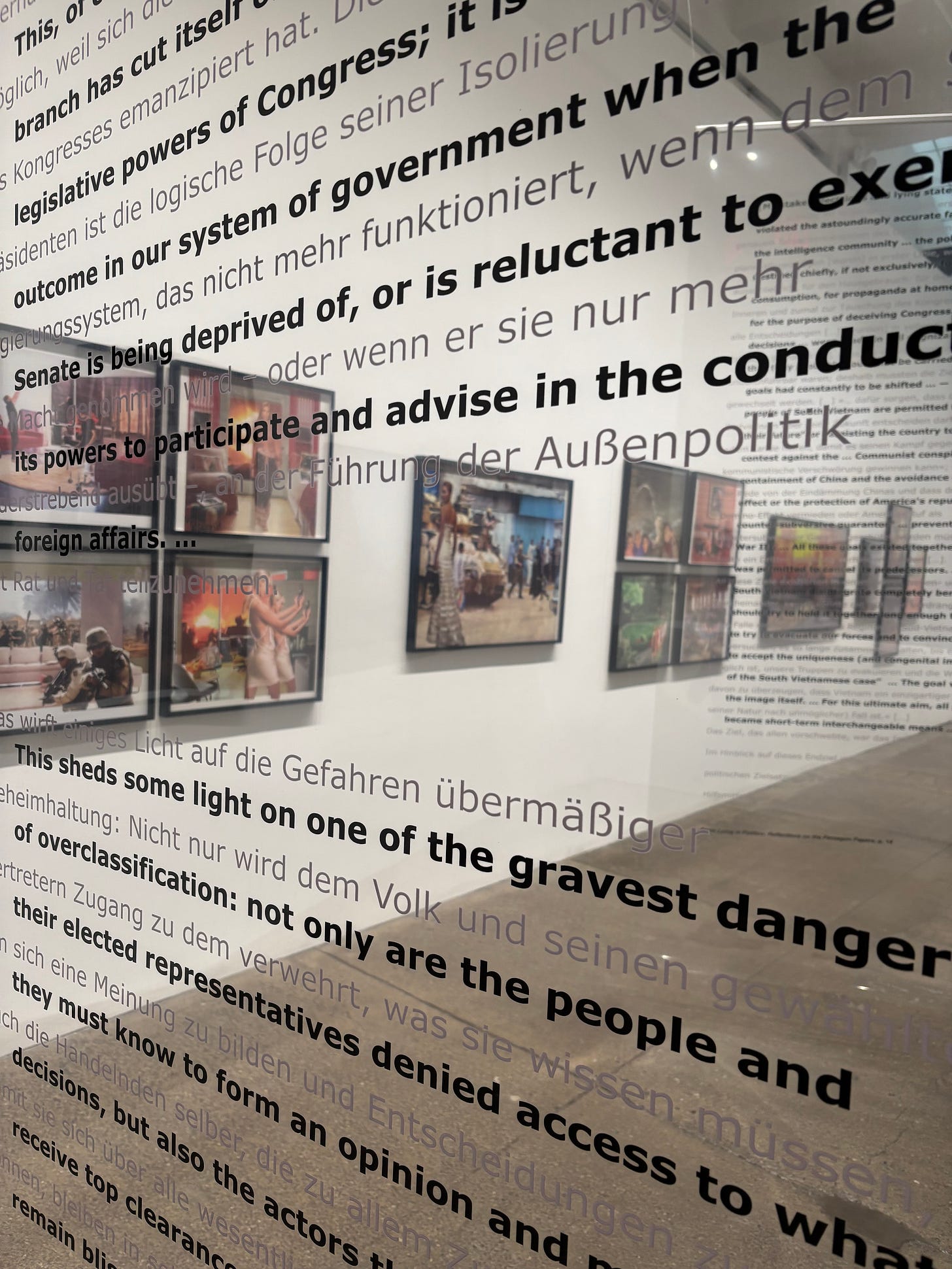

The show presents work almost wholly in retrospect, lots of Rosler’s familiar photomontages around the perimeter of the room, the space erratically blockaded by text-bearing panels of translucent plastic hanging from the ceiling. They render navigation a little awkward, which I appreciated. Their prose—in English and German—renders the reading experience similarly.

Turns out these text pieces comprise one artwork, Reading Hannah Arendt (Politically) for an American in the 21st Century (2006). (“Politically,” as opposed to the other ways one might read her.) The writing, set in row upon row of a squat, generic sans-serif font, is mostly from an essay of Arendt’s that began as a talk at Carleton College called, like the eventual published product, “Lying in Politics: Reflections on the Pentagon Papers” (1972). (See the footage here.) A sample passage begins, “[M]istaken decisions and lying statements consistently violated the astoundingly accurate factual reports of the intelligence community . . . the policy of lying was . . . destined chiefly, if not exclusively, for domestic consumption, for propaganda at home, and especially for the purpose of deceiving Congress.”

You get the picture, and why Rosler dug up the essay at the height of the Iraq War, even if the original was in re: Richard Nixon.

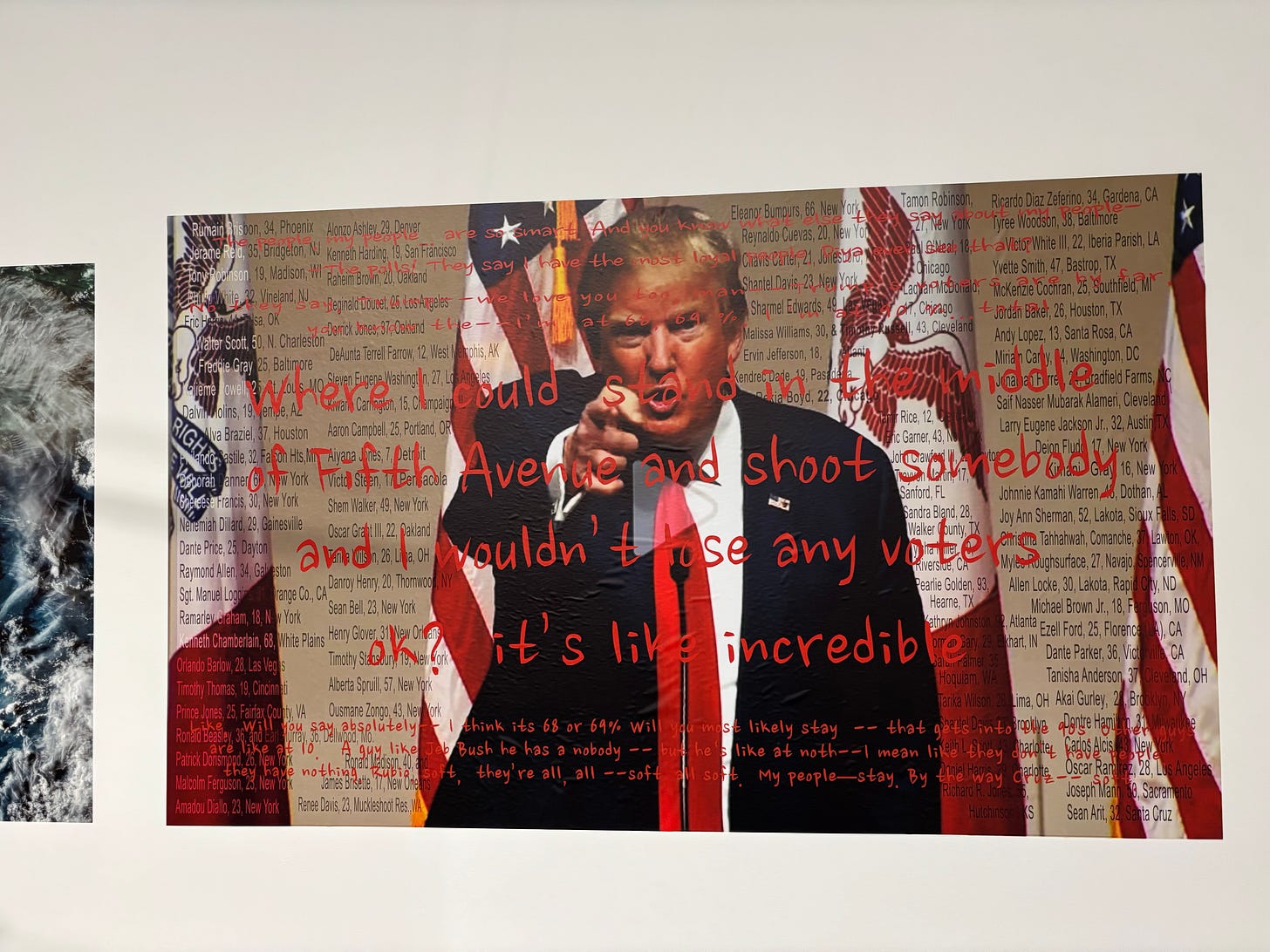

The surrounding photomontages make the same maneuver of pairing Rosler’s anni mirabili, the 1970s, with her later move toward definitive canonization, the early 2000s. The largest chunk of the works come from her indelible House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (ca. 1967–72) and includes the entirety of House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series (2003, 2004, 2008). There are also selections from similar series, for example Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain (c. 1966–72). In an adjacent room, a group of monitors show various videos of protests shot between 2012 to 2025.

I’m breezing through the show because I assume my audience knows Rosler’s oeuvre. The work at hand has been thoroughly evaluated, and there’s little for me to say about it. The original collages are great, their reprises less so. The later ironies are just as vicious, but the individual juxtapositions and compositions worked less well in the 2000s. Or perhaps they were neutered by the irony that had already begun its narcotic drip into the collective ear.

What’s more interesting is what’s happened in the passage of time between Rosler’s resurgence in the ’00s and today. For younger viewers, the Bush Administration seems as remote as the Vietnam Era. Today, the obvious word to apply to Rosler’s approach is cringe. You feel a transitive twinge of embarrassment looking at it. The reasons are simple: her work is earnest and obvious, legible, and bludgeoning in its politics. It’s sincere. Rosler originally distributed House Beautiful as flyers at anti-Vietnam War rallies. It’s art that thinks art can still do something.

A funny thing, though, is that Rosler’s work would seem aesthetically welcome in 2025. The photomontages are practically memes without text, hyper-focused on their moment like the ephemeral viral products of countless randos, compressed and epigrammatic. Like an edgelord, Rosler operates in bad taste, and her irony is vicious to the point where it becomes indistinguishable from lurid humor. The glossy mass magazines she dredged for material were a backwash of imagery fundamentally no different from the slop that sloshes around online. There’s just more bilge now, open to swift and endless metamorphosis in a realm where there are neither viewers nor creators but only iterators. The lack of fixity yields an evanescence that Rosler would in some sense accept, I’m guessing. The aimlessness, even nihilism, she crucially would not.

The people most enamored of digital image making and circulation might in fact admire Rosler if you could get them in the door. She’s their ancestor. On the other hand, they tend to be the people most hostile to looking at historical lineages, since history is a tether to a past, and if they conceive of themselves as doing anything more than jerking us all around, they fancy themselves as breaking free into a bold new world. This revanchist vanguard contains multitudes. The past is fine, if you go back to the Bronze Age or Hieronyous Bosch; just stay away from history. It might blight your precious claim to being original—ironically the most modern aspiration of all.

Syd

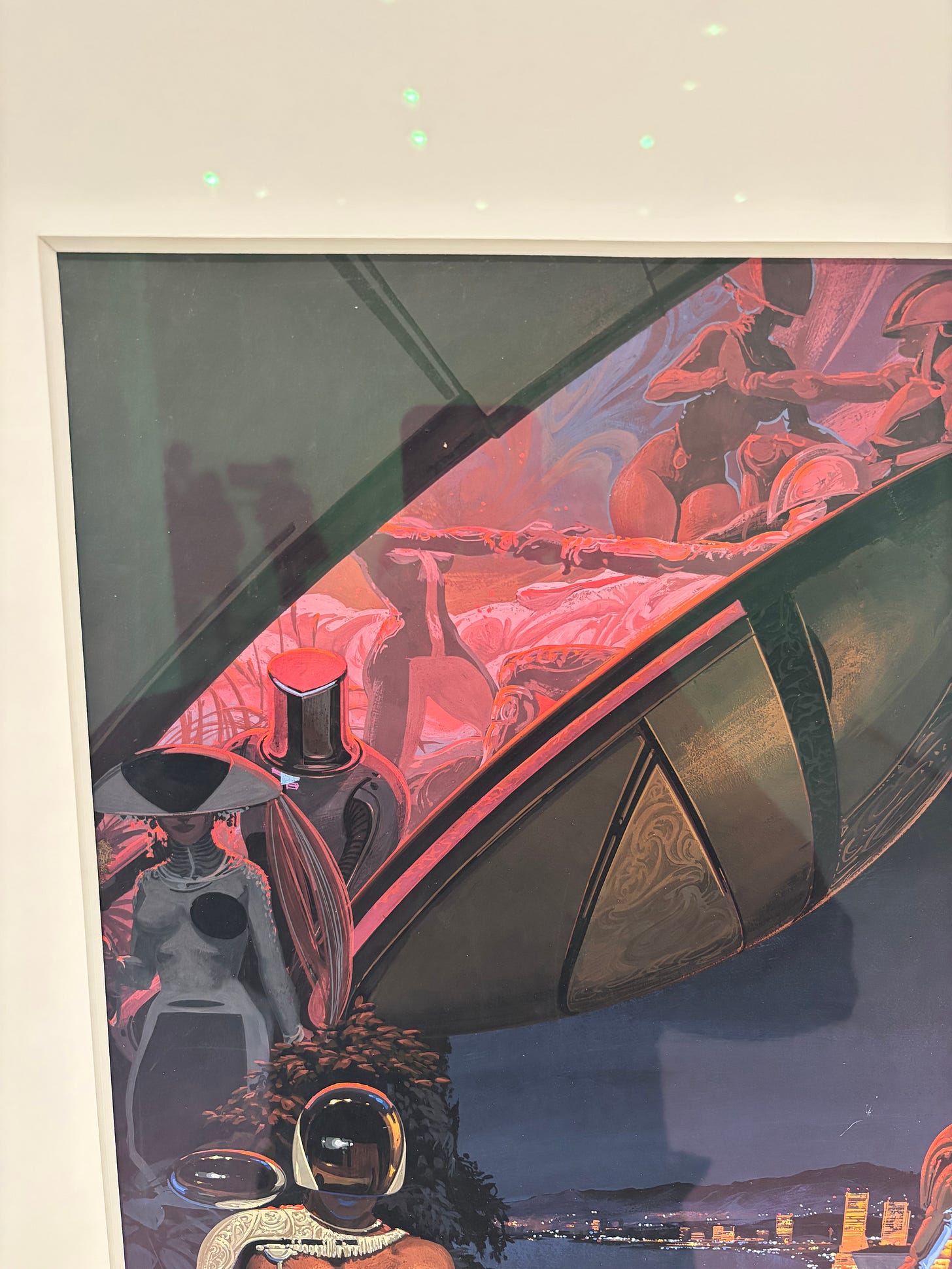

Next door to Truth is/is not—in a space where Rosler herself showed until Mitchell-Innes & Nash closed last year—Syd Mead cocoons outside this thrum and angst; his work is unfussed by the outside world. It’s one of the reasons that the show, titled Future Pastime, is such a delight. You get the immersion in an alternate universe we associate with “outsider” artists, which in a sense Mead is. Everything in a look is cogent, of a piece; there’s no perceptible change over time (at least in this presentation, which spans the years 1969 to 2004), so we can relax without worrying about the vagaries of change that plague the real world or the burdens of—there’s that word again—history.

Mead, who died in 2019, began his career making gorgeous concept art that inspired some of the country’s biggest automakers in the 1960s before his success led him to working also in electronics, architecture, and interior design—then ultimately to a famous role inspiring directors of the most iconic science fiction of the 1980s and ’90s, including Blade Runner, Tron, Aliens, and the Gundam franchise. (Not to mention Robert Longo’s Johnny Mnemonic.) Mead attended Art Center College of Design in LA, graduating in 1959, while across town Ed Ruscha was getting his own design degree at Chouinard (later Cal Arts). Mead wasn’t thoroughly off the radar of the art world: He actually appeared in Documenta 6 in 1977—a capacious show featuring 633 artists ranging from Vito Acconci to Mead to Krzysztof Wodiczko—not long after Rosler finished her classic Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975).

All of which is to say that Mead’s path had certain parallels and commonalities with prominent ones in postwar American art. Much could be extracted from the Rosler/Mead pairing with regard to the military-industrial complex, but I’ll leave that to some dissertation writer somewhere. (Rosler got her MFA at UC San Diego in 1975, a city whose growth was intimately tied to the military, and even today the city has the USA’s largest defense-industry workforce.) With Mead, I’m going to stick close to what’s in the gallery, since his work is rarely viewed in an art setting—little framed gouaches around the perimeter of a white cube.

The most remarkable thing about Mead’s visions helps insulate them from the passage of time: no logos. (An exception is Honda Mural [2004], a motorcycle-racing scene related to a commission by the titular automaker.) Perhaps this was a professional necessity. But as it looks, Mead seems to see branding as the scourge that it is, an infiltration of uncouth semiotics that ruins the lines, the ambiance—these are drawings of ideals, after all. I like to think that he preferred to imagine a future without every surface becoming an advertisement.

Sci fi always places a particular stress on the human body and its evolution. Mead keeps his figures taut and tidy. Bodies are present, seemingly perfected, and frequently exposed. But—like the various creatures and contraptions depicted in races in a number of the works on view—the people always appear static. Mead was curiously bad at, or indifferent to, creating a sense of dynamism or motion. (Is this a result of illustration training? Could someone let me know?) This rigidity doesn’t do him any harm when it comes to the racing scenes, which thrill even if they aren’t Manet at Longchamp. In Running of the Six Drgxxx (1983), four-story-tall horse-dinosaur robots thunder neck-and-neck around an arid track on a possibly alien planet. The massed crowds cheer, and in a prescient inclusion, a number of them brandish what appear to be flatscreen cameras on which the race can be seen in miniature, which look precisely like celphones waved to capture a headliner at MSG. The flow might not be there, but the giddiness is.

The curators of the show, Elon Solo and William Corman, cleverly pair that work with an older one, Running of the 200th Kentucky Derby (1975). There the observers cheer on actual equines, and the crowd in the infield is clad in what passes for ’70s leisurewear; but viewers in the grandstand wear cloaks and more outré ensembles, including some crimson-helmeted jumpsuits that suggest the audience may include some extraterrestrials. The 200th running of the Derby will take place in 2075, so we have fifty years to catch up to Mead’s vision. The hovering architecture seems plausible not despite but because of its showy pointlessness, exactly the sort of thing to lure VC.

In Mead’s nightlife scenes, we get more flesh. In Party 2000 (1977), an indoor/outdoor suite affords a view of a glimmering indigo metropolis unfurling into the distance beyond a host of hunky men and busty women, all nicely tanned. Everyone is holding a dinner-plate-size ring—a collar to be bestowed?—that seems part of a game of seduction or sheer sexual abandon. They tend to wear revealing garments recalling the odds and ends of a suit of armor, often little more than a helmet, or else a skin-tight jumpsuit. Mead’s figures very often face toward some event or vista in the beyond—a landscape, a boat race, a car show. This tactic draws us into the work as fellow viewers, part of the crowd. We’re drawn into the fantasy.

Per the exhibition’s title, Future Pastime includes little of what passes for daily life, almost no depictions of work and its tedium. A notable exception is the farming taking place in Space Wheel Interior (1979). That vision is sterile and posthuman, a world of zero employment—and here it might be worth mentioning that one fancier of Mead’s is Elon Musk, whose Cybertruck is apparently inspired by Mead’s designs for Deckard’s car in Blade Runner. (Musk’s interpretation is a predictably toddler-brained imitation of Mead’s vision.) The dialectic between Rosler and Musk is never more salient than it is here, where the narcotic possibilities of looking away from reality are contrasted with Rosler’s attempts to puncture the media’s occlusions of it.

The curators’ wise focus on leisure makes for a fun show and flaunts Mead’s strengths. At the same time, the choice heightens the work’s already-great distance from our lived reality, and the contrast with Mead’s accidental neighbor next door. Mead is busy creating a utopia; by the time he got to the point in his career at which we first glimpse his drawings here, he had already left beyond the quotidian concerns of car design. His gifts lay elsewhere. A lot of elements in his gouaches levitate, which suggests a desire to transcend, to float away from the bounds of the earth, the tedium of the real, the tedium of the human. And all those races give a whiff of running away from it all.

But a loop around a track is not an escape; it’s a figure of one, where you beat your competitors and for a moment, when you break the tape, you feel free. In one of the moodier works on view, Mono Pod (1974), a number of characters are enclosed in the one-wheeled, tortoiseshell-shaped titular apparatuses. For once Mead offers a vision that seems less than 100% ideal, contrasting those isolated pod wearers with lots of other people chatting and having a seemingly good time. It’s an implicit acknowledgment of the glue of small talk, the power of a knowing silence.

Note: The curators of Future Pastime are giving a talk at the gallery on Saturday, May 10, at 4 pm, with help from one of New York’s literary treasures, Michael Bullock.