The Virtues of Ambiguity

Kianja Strobert's quietly gripping show at Marinaro. Plus tasty Spanish tinto, LDR, and a special message to a certain someone . . .

A peril of being a critic is that on the street, in the showers at Blink Fitness, while meditating in the Key Food cereal aisle, people are constantly asking me: What is it that makes good art so different, so appealing? My response is usually “Can I borrow $20?” But when feeling expansive, I say . . .

I don’t know what I say. Because I’m by nature antisystemic and in favor of mercurial (but moral, if you insist) inconstancy, I blurt something out to suit the context. Maybe because of the vagaries of my sensibility, though, one thing I am always drawn to in art is a refusal to be readily classified, a positioning that creates a magnetic uncertainty in the mind of the viewer, something that flips between one meaning and the next.

One current NYC show that pries open a perfect space of ambiguity—closing April 5, unfortunately—is Kianja Strobert’s quietly gripping Pennies from Heaven at Marinaro gallery.

At first encounter, the exhibition might seem to be starting a conversation about public vs. private space. On the third floor of an old cast-iron building at Great Jones and Broadway, you find a facsimile of the surrounding urban environment, or part of it: a room full of ungainly life-size park benches made from papier-mâché and chicken wire over wood frames, all amply painted a particularly nondescript shade between chimneysweep chalk and gunmental gray.

This homely coloration and the works’ rough texture should be off-putting. But instead, they’re inviting. And in fact the viewer is invited to sit for spell on the benches, which end up being more comfortable that the ones you’ll find a few blocks away at Washington Square. Your companions will be the appurtenances that rest here and there alongside you, which include mocked-up dumbbells, the occasional photograph or printed matter, and stiff strips resembling towels or the very strips used to make papier-mâché itself. One bench balances a plastic version of the old Macy’s “Medium Brown Bag”and a yellow prayer candle. Wall works of the benches’ facture further develop the cloth-strip motif; one suggests those frames hung with spongy cloth that lick your car clean when exiting a car wash, while another comprises two large strips suggestively twisted in labial curls, with a couple faux pearls piercing each lip.

What’s going on in this main section of Strobert’s show is complex; the seating option quickly comes to seem a recognition of the fact that you might want to sit down and think things through. What first appears as a single installation crystallizes into a set of individual sculptures that cannily, awkwardly create internal physical tension. Strobert uses the bench shape as a long platform available for iteration, a pedestal cum visual see-saw carefully calibrated between objects like a sherbet-colored off-brand crewneck sweatshirt in a box at one end and, toward the opposite, a swath of gray mâché resembling a bath towel, half on the bench and half drooping rigidly toward the floor.

Then just keep waiting, thinking. The sculptural success of these works yields to the bench’s function as a location to gather elliptical sets of signifiers—a kind of poetics that is, like so many artists’ works, indebted to Rachel Harrison. Untitled #6, for example, features a sizable fake barbell at one end and at the other a calendar bearing a photo of a rose between two constructivist abstractions. There’s a clear subtext of gender here and in some of the other works—in the body of work’s very facture, which oscillates between female-coded textile and dude-coded bulky massing of form. Despite the oversize vulva, however, the subject and what it might mean remain unstable, irresolved.

There’s a lot more to consider. The small constructivist-style sculptures that appear alongside (and occasionally as part of) the bench works read as distressed abstraction—one of the artist’s declared references for the works, Tatlin, in dialogue with a more sober Franz West. Because of Tatlin’s architectural and monumental notions, these works can, if you allow them, expand in size. Standing next to the benches, they’re mock, maquette hunks of cityscape; perhaps they’re saying something derogatory about the monumental, in both senses. Via the fact that Strobert attended Cooper Union in New York, you can even bank shot a reference to the longtime dean of its architecture school, the anthropic-abstract-narrativist, ultimately hard-to-categorize John Hejduk, though he died the year she finished up there.

Don’t get up yet. There’s still more—for example, a subtle narrative among and across the benches that speaks to downward mobility. Strobert titled the show after the Depression Era tune “Pennies from Heaven.” The scattered hints of middle-class domestic life—that Macy’s bag, the glossy magazine clippings—feel a little lonely, at sea. There’s one work that features, of all things, the text of “Ozymandias” featured on something that looks like a page from the aspiration porn World of Interiors. The deliberate hackiness of the Shelley choice tosses its meaning up for grabs, but multiple balls come raining down. The notion of all things passing, the notion of real inevitable decay for whatever one builds in art or life, exist in dialectic with the comedy of wielding the most heavy-handed poetic reference this side of that beast slouching toward Bethlehem. The monument reappears in those vast and trunkless legs of stone; and there’s also the notion of a “liberal” education and what it perhaps ends up being worth.

And just when you think you’re done, there’s a whole jaunty room of other works, colorful mâché towels arranged as if on an irregular clothesline.

You have through this Saturday to experience firsthand Strobert’s exquisite field of uncertainty and contemplation. Go to Marinaro and rest thee. Or, in the words of the most exegetical figure in Western culture, quoted in one of the many English translations of the four gospels that disagree among themselves what He did and who He was: “Come away by yourselves to a desolate place and rest a while.” St. Mark means desolate there, I think, in the best possible way.

Advertisements (for Myself)

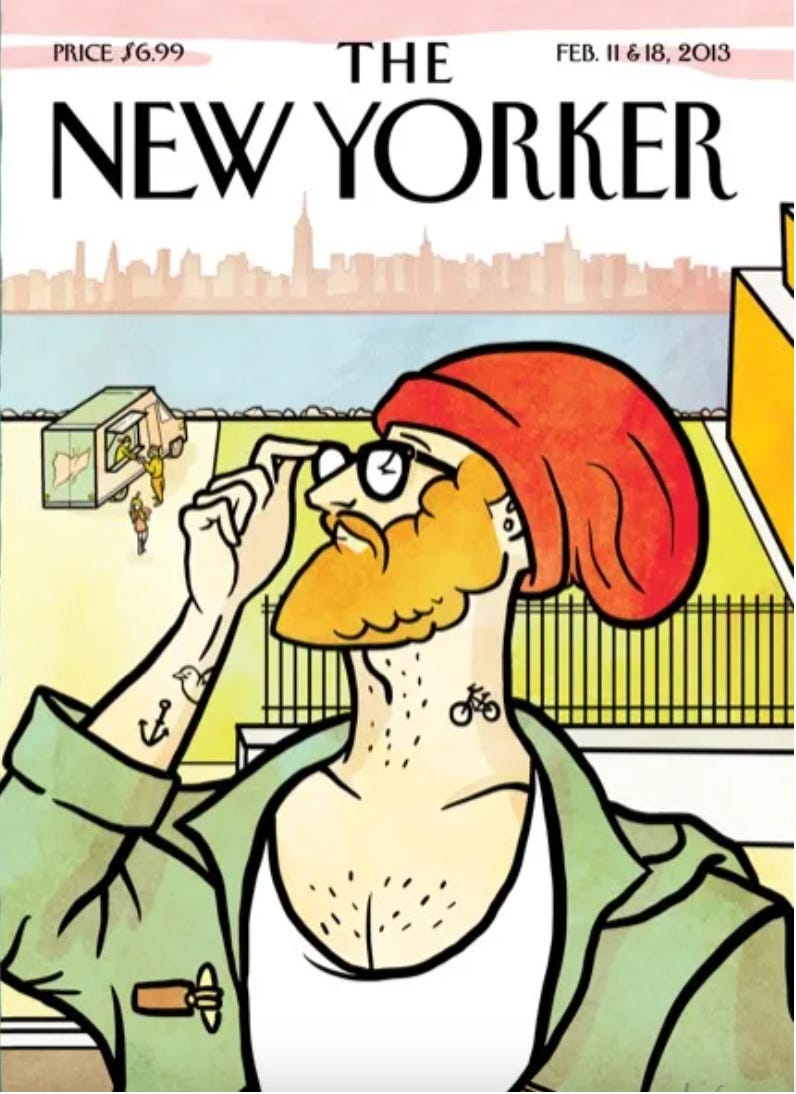

Experienced art critic seeks experienced editor in chief. Remnick! If you’re reading this, that means you got my email I hope my CV wasn’t too long; you feel the pressure to pad those things when applying for a job at the world’s most important magazine.

Hope you enjoyed the Strobert essay above. I know you prefer coverage of the big stuff, but hey, I like what I like. I’ll show you what I can do with Casper David Friedrich next week. Meanwhile, you have my number. I’ll meet you at the Odeon any old time.

Wine

Paradigma Monastrell 2019. I once spent nine months in Provincetown thanks to the beneficence of the Fine Arts Work Center, which awarded me a fellowship in fiction writing on the basis of a doomed novel manuscript. In retrospect, it resembles many books that have since circulated to niche acclaim that I never want to read. Vaguely autofictional, the confusion of youth, timeless truths dissolving into degenerate ironies, a poignant yearning for connection beneath sexual misadventures, blah blah fucking blah. People do still seem to like that sort of thing, so if you’re an agent or publisher, get at me.

(And shoutout to the person more or less solely responsible for my lucky break, the highly underappreciated novelist Jaimy Gordon, whose horse-racing epic Lord of Misrule won the 2010 National Book Award. Thank you, Jaimy. I’ve never received a higher compliment than your telling me you were impressed by how eager I was to make my narrator unlikeable.)

Cape Cod is bone-wet cold and dark in the wintertime. Most establishments close during January and February, so I too-often visited a nice, year-round wine store on Commercial Street, Glass Half Full. During my free time, I would spend no-doubt annoyingly long periods perusing the offerings. Thus I became acquainted with the proprietor, Jerry, who regaled me with tales of his life in NYC in the 1970s and kickstarted my novice curiosities about wine. In a way, he’s responsible for Spigot.

Foremost among Jerry’s budget recommendations was a Spanish wine called Monastrell. When I recently saw a bottle of it called Paradigma in my local shop, I bought it for old times.

Monastrell is the Spanish name for Mourvèdre, a grape that the French mostly use for blending, often in the characteristic GSM (Grenache-Syrah-Mourvèdre) combo of Côtes du Rhône. It’s a warm and satisfying wine, ideal for sipping in a cold shack with the door blocked by eight inches of snow. It’s got enough backbone to stroll upright with food but is also simple enough to drink on its own. And, crucially, you can often get it while spending less than $20.

Paradigma is rustic but lighter than most Monastrells, fruity up top and minerally at the bottom with not a lot in between—but fruity and gritty are two things I like. As it goes along, it gets a little woody and loses its smooch of strawberry, but it remains more than drinkable. If you’re finishing a bottle alone, the finale might be a little harsh, but it’s no more than smoking a Marlboro Light with the last glass. Highly recommended for Europhile oenophiles in an era of 100% tariffs.

Music

As I walked across town after visiting Strobert’s Pennies, the American Legend brand sweatshirt she archly included in her show became entwined in my head with our oh-so-American Lana’s “Living Legend.” Guns in the summertime, horses too.

I appreciate you taking the time to document these things and share your thoughts. I especially appreciate the photos you include, since I am rarely in a position to see in person any of the shows you discuss.

Your point on ambiguity is well stated. What excites us is so often the space of questioning that juxtaposition and mutlipolar discourses make available within us. Sometimes great art is pointing to things that appear to stand apart, challenging us to connect them, and sometimes great art is prying apart things, asking us to experience the space between them or do something about it. Art as artifact of a struggle, an invitation from the artist to engage with that specific struggle on your own terms, generating unpredictable friction in each viewer.

thee best lana song