From the Point of View of a Turtle

Laura Owens at Matthew Marks. Plus John Divola, Sicilian red wine, and weed store kratom set to music.

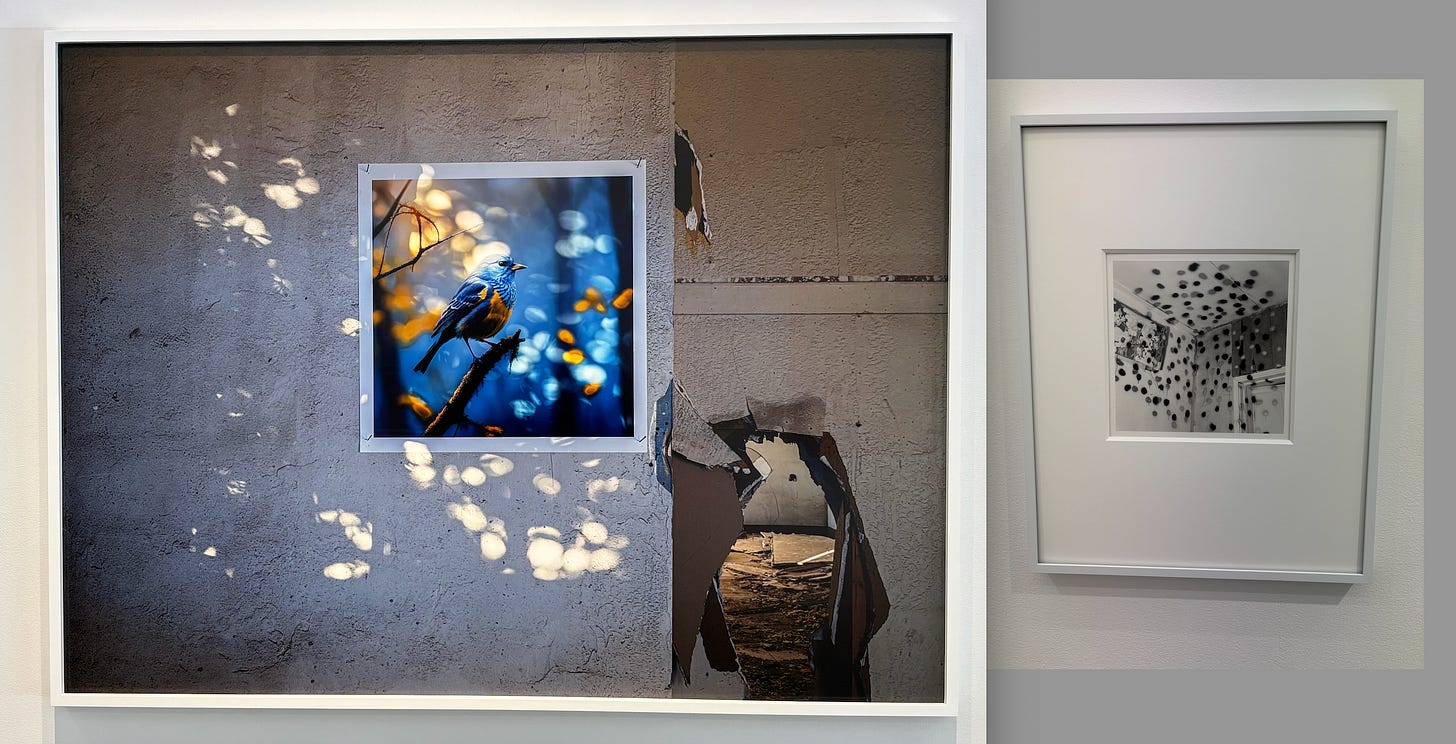

The John Divola show at Yancey Richardson just closed; I managed to catch it on Saturday. Divola, one of the more underappreciated ’70s American photographers, first made his mark (bad pun, sorry) by spray-painting spirals, loose grids of dots, and other patterns inside abandoned homes in the Los Angeles area, then photographing them. His Vandalism works (1973–75) were a perfect merger of New Topographics with a more conceptual, more abstract, interiorized viewpoint and a smidge of ’70s performance. As opposed to figures like Robert Adams and Lewis Baltz, who captured a sterility and vacancy at the heart of suburban life from the outside—rendering impenetrable facades with an undertaker’s cold hands—Divola turned broken-down, open-to-the-elements semi-ruins into theaters where the actors were abstract mark and light.

Divola’s show at Richardson offered a side room of vintage gelatin silver prints from the Vandalism series (available in book form for a very reasonable price) but was in fact a showcase for new work from his series Blue with Exceptions (2019–24). Over the years, Divola has at times added to his decrepit mises-en-scène found amateur artworks and other imagery to create picture-in-picture effects with lo-tech means but masterful abilities with light and framing. In some works from Blue, made at the decommissioned George Air Force Base in Victorville, California, he hung various prints of AI-generated images of birds—a logical extension of what he’d been doing and a funny/odd way of approaching the issue of AI in art, which practitioners in various fields have been crawling all over each to make the best gimmicky use of. Divola’s Blue works can feel a bit stiff, but they’re also skillful and searching, committed in a weightlessly brute way of juxtaposing the clunky material world and the machinic one.

I hadn’t expected Divola’s show to segue so smoothly into my actual destination, Laura Owens’s exhibition at Matthew Marks’s side-by-side spaces across the street. But like Divola’s, Owens’s show is rooted in notions of home and domestic life. I’m sure I’ve seen other gallery shows so transcendent and affecting, but nothing is coming to mind. It’s almost too good to write about.

In the larger of Marks’s two spaces, Owens uses her abilities with illusion, depth, and design to mock up an oversized interior with restraint and a supple hand. Beyond the entryway is a trompe l’oeil half-wallpapered room, complete with rendered rips in the leafy pale yellow pattern that reveal fictive layers underneath. There are also filigrees such as extension cords, moldings, a coiled phone line looped through a strawberry donut. The presentation is witty and light, and the large abstract canvases Owens has hung condense the same techniques and motifs that are literally on the walls—orchids atop the laurels. The building’s high ceilings are emphasized just so, to hint that you’re seeing things from a child’s point of view. Above one baseboard, a trompe library card for Laura Owens of Norwalk, Ohio, hangs in midair, very much a floating sign, a nod to meaning in suspension.

Two thick cutout swinging doors in the back wall lead into the next room, likewise completely muraled but to a vivid indoor-outdoor effect, like you’re passing into a backyard. Here Owens’s virtuosity is on full display. One swooping cutaway yields to another, blue-green shapes conjuring sky or ornamental ponds, brilliant gold patterning segueing into pure abstraction. A trellis holds back a swelling green hedge; pink and purple flora—or is that more wallpaper?—erupt elsewhere.

This sumptuous, depthless environment yields to a final room that’s the opposite of the others—dark, empty, and tiny as a closet. Four people can gather inside, not a soul more. In a perverse move, this niche has been turned into a screening room with the projection, smaller than many TVs, running high up at ceiling level. Office work has ground down the cartilage between a couple of my cervical vertebrae (send Percocet), which made this experience a teense less transcendent than the rest of the show, but artist and viewer alike must suffer for great art.

The performers in the video are two puppet crows. Though the piece is 80 minutes, I went to see the show twice and strangely caught the exact same portion, so I don’t want to be definitive in my assessment. [CORRECTION: The video is 18 minutes, which explains why I saw the same portion twice on two different visits.—DLA] The video’s Beckettish absurdity and its essential unwatchability make it open ended. But what I saw suggested comical everyday conversation between a parent and tween-ish child. The former, for example, suggests an idle trip to Starbucks for a snack, a let’s-get-you-out-of-the-house maneuver that’s immediately shot down. Why go buy a danish? Why don’t go we steal all the cash in the register, so we can buy all the danishes we want? Parent crow suggests getting a cat; kid crow meets that idea with a similar disdain: we’re crows, a cat wouldn’t want to live in a tree. Human, familiar, funny: the video is a brilliant allegorizing of possible inhabitants of the space we’ve just been in.

All this would be impressive enough. But it’s in Marks’s other space where the show leaps into another register entirely, taking advantage of the theatricality latent in Owens’s rich, allusive domestic interior. There, one finds a number of tabletop fabric-covered boxes like miniature chests-of-drawers, holding within them a host of volumes like those a child would have, with lots of scrapbooks and workbooks. Titles range from Business Penmanship (which is filled with colorful squiggles à la the artist’s familiar blown-up brushstrokes) to a Holly Hobby folio of saved birthday cards to the adorable Plants from the Point of View of a Turtle to a book of baby pictures, the vintage of which strongly suggests they could well depict the artist.

Beyond this memory palace, anotherly vivid trompe l’oeil room awaits. But the center of gravity lies with those books and boxes. One of the more mysterious items to be found, ill fitting its drawer, is a Honeywell fire alarm annunciator. Owens is, as is well known, a Los Angeles resident; she’s practically an icon of the city’s art community. And so I found it impossible to come upon this bland box without January’s fires briefly clouding over the room. With this shade of discord, Owens’s bravura, at-times giddy, droll, and reflective exhibition becomes also mournful. Looking back at childhood artifacts can be a little gloomy, considering how easily it all can be lost. The show reminds me of cleaning out an old house, perhaps one’s parents’, with a tinge of sadness yet a keeping on. There’s an urge toward growth and renewal that’s keenly mortal, joy but—ironically, for such an deft illusionist—no illusions.

Wine

Savino Nero Sichilli Vendicari 2016. Exciting news (no really): I was fortunate enough to be selected by the Amant Foundation to take part in their Studio and Research Residency in Siena this summer. My deep gratitude goes to everyone who was involved in the nomination and selection process, to anyone who’s ever given me a break.

To celebrate the residency, I decided to pop open a bottle of Italian wine, from Sicily. Yes, I know, it couldn’t be more geographically wrong, but I had it on hand, and to be honest, I don’t that much about Chianti or Brunello. I am looking forward to learning a lot about the wines of Tuscany while I’m there, hopefully not to the detriment of my writing process.

Savino Nero Sichilli comes from near Etna, which is, you may recall, an active volcano on Sicily. The wines from surrounding regions tend to be crunchy but also fruity. The varietal of this wine is Nero d’Avola, so it’s not an Etna Rosso per se (wrong grape), but it’s similar. Savino Nero smells woodsy. It swoops across the tongue, acidic—tangy even. It gets more piney as it opens up, gradually developing lots of little urgings, pangs, gentle expressive shards. It’s not melodramatic, but it does evoke an unusual range of feeling. Or maybe I just have Laura Owens on the brain.

Savino Nero opens its hand and offers you a jagged chunk of 70% dark chocolate and some herbs (try it with earl gray ice cream—weird, I know—if you want the spice rack really opened up). And it does offer ripe fruit: especially once you get past an hour of O2, the wine starts to get sweet but retains enough grit to keep it from collapsing into runny pudding. If you can’t find Savino itself, try another Nero d’Avola. If you get the right one it’s a great deal for the price.

Music

The last time I was in South Carolina I took a long walk (inadvisable), crossed a parking lot servicing a few establishments such as The Dizzy Crab and a lingerie store I have not patronized, and jaywalked across a four-lane road (also inadvisable) to visit a kratom shop. Yeah, I’m real like that.

I bought some red maeng da capsules on my first trip. On my second, I decided to pick up a bottle of a mysterious drug—excuse me, supplement—called Zaza, comprising a dusting of kava root atop a sturdy substructure of Tianeptine, a “µ-opioid receptor agonist with anxiolytic effects” that’s legal in many countries but not the benighted US. I have yet to crack open the bottle because I started to worry it might kill me one way or another. Anyway I’m a member of the store’s rewards club now and they send me text-message discounts every couple of weeks.

“Weed Store Kratom” is an ode to life’s ready escape hatches from Ada Rook’s new album Unkillable Angel. I discovered the track thanks to writer/performer Maya Martinez, who recently used it on an IG post. To be reductive, Rook’s music is hyperpop x screamo x ’90s industrial techno, throwing in a reference to Depeche Mode here, a house piano break there. There’s definitely some 100 Gecs influence—and in fact music by Rook’s previous band, Black Dresses, was remixed by Laura Les. “Weed Store Kratom” leans a little more Gecs than the rest of the album. Its bouncy melody, singed but not scorched, hammers your brain with a cartoon mallet until it’s pleasantly bent out of shape, in a gas-station supplement kind of way.