The highlight of the whole thing? The “backstage” area tricked out with locker rooms

1.

It’s not news that the vicious binary quality of conversation online has crept into all of life. Of course then it has afflicted discussions surrounding Doom: House of Hope, just closed in New York, by Anne Imhof, a polarizing artist whose canniest aspects are precisely about how we disperse life onto screens. Lots of people have been excited to say scathing things about the show; lots of people were ready to advocate on its behalf. I kind of want to do both.

Doom was ponderous and mostly bad, but seeing it was a fun thing to do with a couple friends and left you with plenty to think about afterward. During the performance, you could wander mostly as you liked in the amazing confines of the Park Avenue Armory (a particular treat for space-starved New Yorkers). There were two Arts and Crafts bars with alcohol, soft drinks, and snacks where you could rest for a few minutes or half the show. You could check out the merch table. No cash accepted at any of the concessions, for the record, though I refrained from reporting them to the local authorities for this violation of our fair city’s Prohibition of Cashless Establishments.

The most fun thing of all about Doom, however, was that you could talk. Talk was the most important thing about the piece. Even inside the show, during the action, you could chat at basically normal volumes. (Reports suggest that the PA was turned down after the first show or two, so some less sociable bellowing may have been necessary during early viewings.) You could banter and bloviate as you pleased, generating as much discourse during the show as in its wake. Imhof’s art has been most compellingly been read vis-à-vis its brilliant relationship to social media; see Farago’s summary NYT piece and, more important, Carly Busta and Lil Internet’s incisive essay in (sigh) Artforum in December 2021. I’m intrigued by that take on Imhof. That’s why I bought a ticket to Doom, to see how it all felt in person.

But within this vein of commentary about mediatization, Imhof’s work has always been valorized because of the way it spawns images. Though Doom has many of her signature motifs (all the big ones you’ve heard about but also details like musicians shredding on guitar or drums, candle wax, bare mattresses), perhaps Imhof has changed, because now what seemed important was how her work spawns words, and particularly disagreement, rather than images. With Doom, a paradigmatic artist of the Instagram world has made a synecdoche of art in a Twitter/Reddit universe. So maybe Imhof is the genius we were promised, once again distributing her performance in keeping with the logic of social media, just channeling a different kind of platform.

Since I went to Doom, I’ve been thinking a lot about a fragment of a quote I saw plastered on a wall at the Armory Show last fall. With acknowledgment to my associate the artist Paige KB, it comes from a definition she found of memes: VERY BEAUTIFUL IMAGES WITH QUITE A BIT OF CONCERNING TEXT. Note the balance. QUITE A BIT distills the power struggle and arguably the true relationship online between the image and the text that accompanies, magnifies, mollifies, mocks, expands it.

Particularly in New York, where we can devirtualize conversation like nobody’s business, it was natural that an appearance by Imhof would have a catalyzing effect. A world-class artist who’s mostly avoided the city, creating her biggest spectacle yet? Perhaps the latent sense of being long snubbed is why so many locals were irritated by the show. She made us wait so long, and for this! The run of Doom lasted ten days, an increment compressed enough to perfectly focus conversation; a longer run would have allowed discussions to diffuse—and defuse. So it’s only natural that our notoriously yakity city would be yakking about the show. Doom was foremost something to argue about, something to polarize over.

If getting people to talk about your work is true artistic success, Doom is thus an absolute masterpiece. Viewing Imhof as great, however, or if you prefer, exemplary, does lead to a discomfiting question. Is the ability to drive conversation a sign of good art? If so, that would distribute a great deal of the artistry to PR firms. Which is depressing but probably the way it really is. Maybe instead of a show about technology—snooze—The New Museum should reopen with a Cultural Counsel retrospective.

2.

Another major question regarding Imhof remains, for me at least. Where does the work really live? Does her art actually just exist in its mediatization—or alternately, with Doom’s verbal lean, in its lore? Given the vast effort Imhof has poured into this and her other epically scaled works (sponsors here including Citi, Cadillac, and the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs), it would seem unlikely that she only cares about her work’s operation in the networked ether. Its mediatization might be its aspect that’s most avant-garde (if I can use that word without people losing their goddamned minds), but it can’t be the only important one.

That leads to the ultimate question: in the room vs. outside the room. What exactly does a visitor to Doom experience?

Beyond the social media stuff, the most attention-getting conceptual aspect of Imhof’s work is its relationship to the audience. You’re allowed to wander freely, the performers move among you, and various things are happening at the same time. While this dislocation of frame and distribution of agency to the crowd feels kind of innovative within a contemporary art context, it is at the same time familiar to fans of Sleep No More, Halloween scream parks, and Meow Wolf. All genres rely on importing conventions of others, of course, so that’s not a black mark exactly, though it does knock a few points off Doom’s radicality score.

The real issue with the choose-your-own-adventure angle in Imhof, however, is that it’s mostly a sham.1 Maybe the audience was only ever supposed to be promoted to being part of the cast, not co-author. You can walk where you want to walk, say what you want to say, but the artist is invariably telling you where to look. Despite the continuous (slow) motion, there is only ever one primary activity taking place, typically broadcast on a central Jumbotron’s screens and over the PA, while the other stuff going on tends to be hotties striking disaffected poses atop and around Escalades, or doing some walking-dead group shamble to wherever their next mark is. If Imhof’s work promises a degree of liberation of the spectator and a dispersal of authority—and I think it does—it fails to deliver, or declines to.

Doom as it appears within the confines of the Drill Hall is thus an essentially conservative product, another mostly humorless German making a gesamtkunstwerk, setting one of the most famous texts in Western literature in the archetypal environs of the US high school with casting that panders to the lusty eye. Oh, the swollen gas-guzzling Cadillacs. Oh, the locker room and the teens absorbed in their video games. Oh, the hip-hop track from 2012, recited in disaffected yet poignant tones. The prom balloons, the middling pop-punk band. A guy in a bear suit, for some reason, even though the relevant mascots were Tigers, Wolves, and Swans. Oh, the doomed teen love.

Doom began with a streetwear-clad teenager2 climbing onto the roof of a highly polished black Escalade and exclaiming “We’re fucked!” This landed, presumably unintentionally, as a threat against the audience. Making this hamfisted overture even more embarrassing was its swift riposte, another teen shouting “We hope!” My entire evening ended up being spent tugged between this devil/angel duo. On the one hand, I was bored out of my mind by Imhof’s leaden instincts. On the other, I would sometimes become engrossed with moments of impressive stagecraft, music, or acting (especially by Talia Ryder) sparking hope that it all might gel.

In case you missed the précis, Doom is an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, a tale of two horny kids who make the ultimate adolescent mistake of taking things a little too seriously. They end up killing themselves in a scene with which Imhof starts her version of the tale, staging it on the flatbed of a GMC Sierra. If you consider an American-made pickup a clever substitute for the tomb that appears in the original text, you may enjoy Doom more than I did. The pair deliver Shakeperean lines with a deskilled flatness while Romeo takes fatal swigs from a bottle that looks like a denuded Fireball shooter. The suicidal drive is, I suppose, what drew Imhof to the material; I have been told that a particular gesture made by performers singly and en masse during Doom, pointing a finger pistol at one’s own head and pulling the trigger, occurs in other of her works as well. Trigger warnings aside, it looks ridiculous when a line of hot youth coordinate the move onstage.

We’re fucked! Yeah Anne, we know. The supremely obvious fuckedness of everything in 2025, especially in the US, undercuts whatever the artist imagined as the piece’s commentary on America. (Never go somewhere and tell the locals all the things they’re doing wrong, unless you do it with a coyote.) There’s nothing ominous about Doom, despite the zombiefied Montagues and Capulets stalking around, the packs of youths enlarging the fashionably located holes in their jeans by crawling half the length of the Armory’s massive Drill Hall. Hot people in streetwear stewing in a pervasive sense of angst and doom? I get that on the subway. The notion that Imhof’s MO is somehow cutting-edge is the most unpleasantly lost illusion of the performance IRL. This shit seems fusty, ironically old.

Of course, Imhof may never have intended to hitch her star to being hypercontemporary. Overzealous interpreters may be to blame for overdetermining her aesthetics and pigeonholing her work. How much of a Balenciaga vibe was there to Doom, really? The artist has maintained a more or less consistent evolving aesthetic over the years, which suggests that she’s comfortable wielding a particular set of elements, happy with what’s in her toolkit. The show seems dated because it appears as an artifact of the time that always feels oldest to us, the just-past; it doesn’t strain to trend chase.

Doom includes a couple of declamations that might be interpreted as clapbacks. I missed them, unfortunately, either because I am hard of hearing or because I spent 20 minutes (or so) at the bar and otherwise wandering the Armory’s capacious front of house. One apparently involved texts by and obituaries of dance critics, among them Arlene Croce’s infamous 1994 anti-review of Bill T. Jones. Per an Imhof aficionado, the broadside was likely in re: old complaints that Imhof hadn’t been doing “real” dance—a dumb complaint indeed.

3.

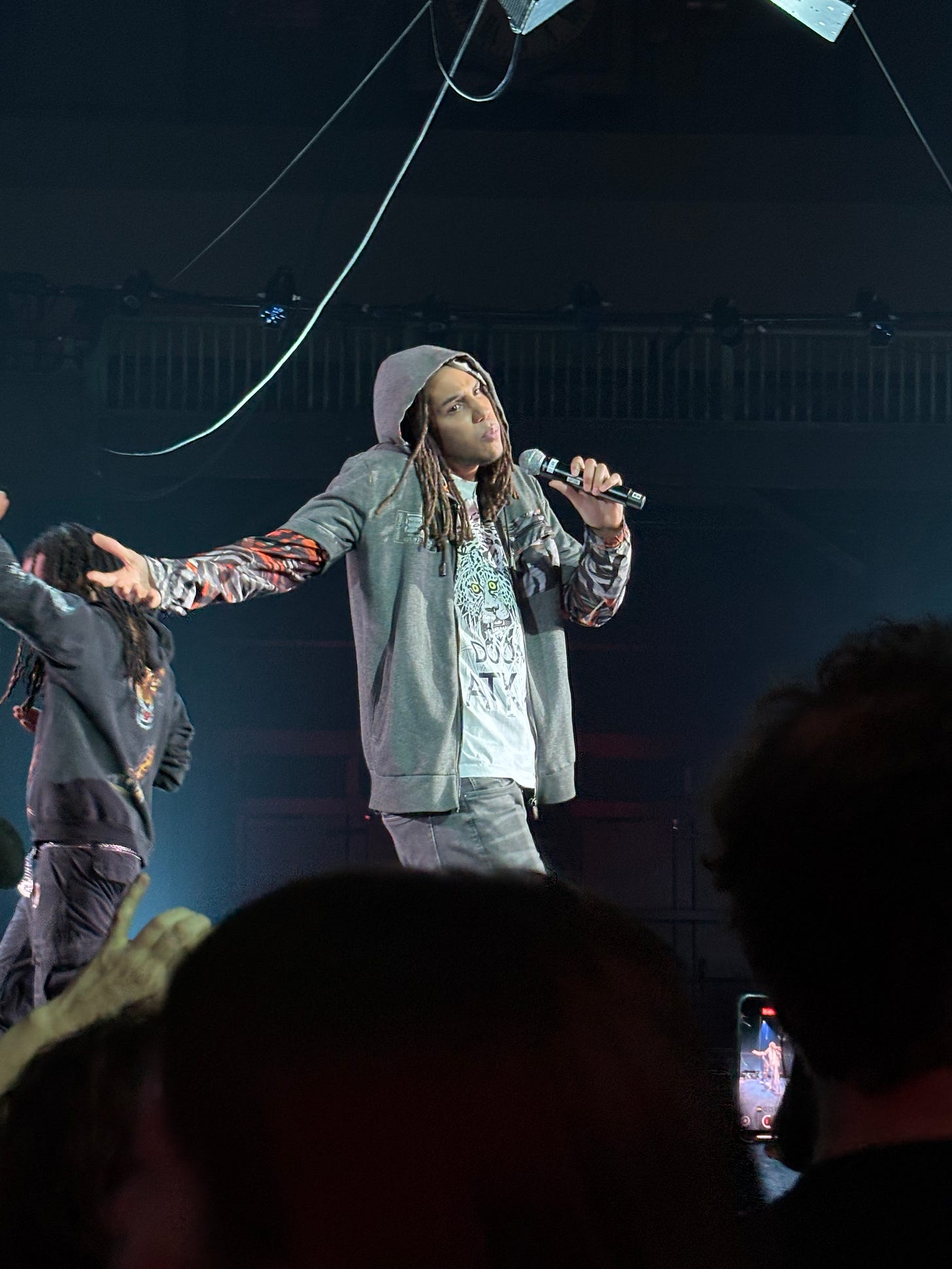

The irony of real-dance enthusiasts grousing about Imhof (if that ever happened; see above re: lore) is that in the end Doom is saved by dance. Generally speaking, the first hour was bad. The second was galvanized by a performance of a few songs by the French-German rap artist ATK44, the breakout star of the whole enterprise, and a period of relative frenzy that included a couple of the show’s most compelling moments, both involving Imhof’s muse Eliza Douglas—one in which she took center court and scrawled with black marker all over her naked torso and that of another performer, another that broadcast her on the Jumbotron from an unknown location dumping bodega-size candleful after candleful of burning red and blue wax into her mouth and down her bare chest.

Some time after these events Imhof took on the balcony scene, which underscored how vital video was to Doom. Much of the action throughout was broadcast on the Jumbotron, a stadium-scale four-screen monitor set aloft. Clearly this was a strategy for making the action more visible. (Another running complaint with Imhof’s work has been, apparently, that the staging makes it hard to see what’s going on.) Her use of video with this level of pervasiveness is new, and it was a great success. The AV design cleverly included a few seconds’ delay on the audio but not the video feed, so that if you were proximal enough to see R and J doing the old “Wherefore art thou,” you could also look up and see them on the screen but with their speech out of sync—shot at intimate range with an iPhone by a girl in a white blouse and schoolgirl skirt. The resulting disjunction said a lot about what’s lost and what’s gained by dispersing our selves and bodies technologically. Shoutout to the Wooster Group for their long-running experiments in this vein.

The third hour of Doom became very good thanks to a turn to, surprisingly yet tellingly, classical music and ballet. Accompanied at times by Bach piano sonatas, Devon Teuscher, principal at American Ballet Theatre, performed solo and in ensemble as Romeo in a lengthy sequence that could fairly be described as moving. However powerful the appearances by Teuscher and ATK44 were, however, it’s hard to ignore that what catalyzed Doom’s audience—and what seems much valorized by reviewers—were not amateur bits or group theatrics but rather the moments when Imhof platformed performers of unquestionable talent and let them cook. The reliance on Bach and ballet to effect a climax pointed back to the show’s ultimately conventional underpinnings. Take Doom to Luna Park or off-Broadway and it would blow people’s minds. Imhof as the new Laurie Anderson. Is that a bad fate?

The corps de ballet moment led the way to a conclusion that, just like the entire show, mixed impeccable staging with ludicrous choices. Here Imhof slammed the dance into a po-faced acapella rendition of a garbage song by one of America’s worst bands—“The End” by the Doors. It was sung in part by Douglas, who despite her charisma couldn’t do a thing with the lugubrious material.

The closing invocation of Jim “Bloat” Morrison is an apt way to sweep up the scatter-art fragments that make up Imhof’s show. The Doors’ musical merits are, let’s say, debatable, but Morrison, a dumbass fake poet who managed to make being a ’70s rock star seem uncool, did a great job of keeping them in the papers. They were and remain something to argue about. Is their “House of the Rising Sun” an all-timer or just a shitty ripoff of the original? Did the Lizard King pull his dick out that night in Miami or did he not? There are numerous photos from the evening, but who can really say? You had to be there. I guess? Sure. But the less you know, the more fun it is to argue about.

The single liberation from the author’s invisible yet firm hand lay in the creation of a discreetly entered, brightly lit “backstage” in a spacious corridor running along the length of the Drill Hall. At the ends are two locker rooms where performers slip out of character to talk among themselves and change clothes in full view of any spectators. The middle rooms include a computer station with a gaming rig and some chuckling kids fucking around on it. While I was idling in the area deep in hour two, Romeo and Juliet strolled past me giddily and threw themselves on a bare mattress alongside an inexplicable tableau of four busted iPhones. The lovers curled up to nuzzle and nap. I waited in expectation that someone would arrive to play a tune on the room’s only other furnishing, a keyboard preset to “Bright Vibe Mk 1,” or that a camera operator would walk in and some pentameter might get thrown around. But after ten or so minutes I left. The feeling of “real life” combined with the protagonists’ hidden-away presence gave Doom a frisson that it otherwise so often lacked.

I use “teenager” et al. in the sense in which it’s used in pornography, connoting an average age of about 23.