Stultified by the Conventions You Seek to Recycle

Rita Ackermann and Julian Schnabel. Plus a light Italian red and Spigot Radio with Johanna Fateman and Isabelle Frances McGuire

The Spigot Radio Hour

Enormous thanks to those who joined me in the studio for Ep. 2 of the Spigot Radio Hour on Montez Press Radio—Tom, of course; the various others hanging out; surprise discussant Paige K. B.; and most of all, my two guests, critic Johanna Fateman and artist Isabelle Frances McGuire. These days, Fateman writes most frequently (and always eloquently) for 4 Columns, while McGuire has excellent new work in the newly opened group show at Artist’s Space.

While the guests were invited according to intuition and a bit of chance, it turns out that they both have sidelines as musicians. Fateman is, as you might know, is a member of Le Tigre; on the air, she confirmed that she was indeed the lyricist behind “Mediocrity Rules” and “Yr Critique,” the latter of which features the lines “I think you're pretty smart / But you act like such a jerk / I can't stand yr fake rebellion / Misdirected and anti-art.” Tough but fair!

McGuire, meanwhile, is a member of the Chicago-based Suicide Moi, who take their name from an album by an implausible ensemble fronted by Jean Baudrillard, and including Mike Kelley, that appeared only once as part of the Chance Festival at Whiskey Pete’s Casino in Stateline, Nevada, 1996. By coincidence, if you visit PS1 now through September 9, you can learn more about the Chance Festival in the Reynaldo Rivera retrospective. The LA-based photographer shot the event.

As for McGuire’s Suicide Moi, they’re working toward recording an album. Meanwhile, you’ll have to make do with this live clip featuring McGuire and their bandmates, Julian Flavin and Liz Vitlin.

Wine

La Kiuva Rouge de Vallée. I’m an idiot when it comes to Italian red wines. I get the outlines but have no intuitive sense of it. Yes, I know you can always pick up a bottle of Montepulciano when you need something cheap and easy, and if you have a sweet tooth like me, you’ll love a Ripasso. But Chiantis have been historically so oversold that the designation feels useless, and the Nebbiolo-based wines of the north are too expensive and meant for heavy dishes that I rarely cook. Invite me over for rack of lamb, and I’ll bring over a Barolo.

It’s white wine weather at this point, but last weekend I was craving one last red. The sales clerk recommended La Kiuva, a blend of various grapes none of us have ever heard of and a Nebbiolo clone, which makes up about 70% of it. Assuaging my Italo-oenophobia (ironic, yes, I realize), they explained that it came from Val d’Aosta, which is practically the Savoy—and thus safe for me to drink. La Kiuva is a coop that grows grapes on the side of the Alps, so the production is small scale, the grapes harvested by hand on slopes too steep for a tractor.

And it’s good. Because I’m weak-minded, La Kiuva tastes to me like the French wines I like, a cross between a granite-y Beaujolais and a light Bordeaux. In distinction to those two, it’s herbaceous, and it starts out too sweet, its only real flaw. With some hours, however, or if you wait overnight, the sweetness fades and it becomes more minty, like well-worked nicotine gum. It’s great with light food or without any food at all, and a great deal—I’m honestly surprised you can get it for under 20 bucks.

Art

Like a dog snacking on vomit, I was drawn to Chelsea recently because three of my least favorite artists currently have shows up. I made it to two of them, Rita Ackermann and Julian Schnabel. I will leave it to you, dear reader, to guess the third.

The notion that Schnabel was perceived as historically significant has always struck me as absurd. But a character as beloved as Rene Ricard found it within himself to pronounce, “When I saw the first plate painting at [Schnabel’s] studio, I knew immediately that no matter what I thought, I was looking at one picture that would reinvent everything.” I assume the cocaine was cleaner in those days. Everyone loves Mary Boone now, but don’t forget: she’s responsible for inflicting Schnabel upon the art world, along with other groaners like Ross Bleckner and Francesco Clemente.

Maybe Schnabel’s crushed plates looked anarchic in their moment, conjuring mayhem when viewed in context in the New York City of the late ’70s and early ’80s. But judging from the examples on view at his son Vito’s gallery—nice job, nepo dad—that’s hard to believe. Schnabel was no Gustav Metzger. His deliberately arrayed crockery is static. At the same time, the way he applies paint is incredibly lazy. It’s remarkable that someone who clearly cared so little about painting also didn’t have a punk bone in his body—and in the heyday of CBGB, no less.

Of course clowning on Schnabel is too easy. Ackermann’s case is more complex. She has some merits, or had them, but fundamentally, like Schnabel, her long-term success is a triumph of persona rather than what’s on the canvas, and illustrates how a blue-chip gallery can pluck up an artist on the basis of social cachet, then manufacture consent for their long-term career.

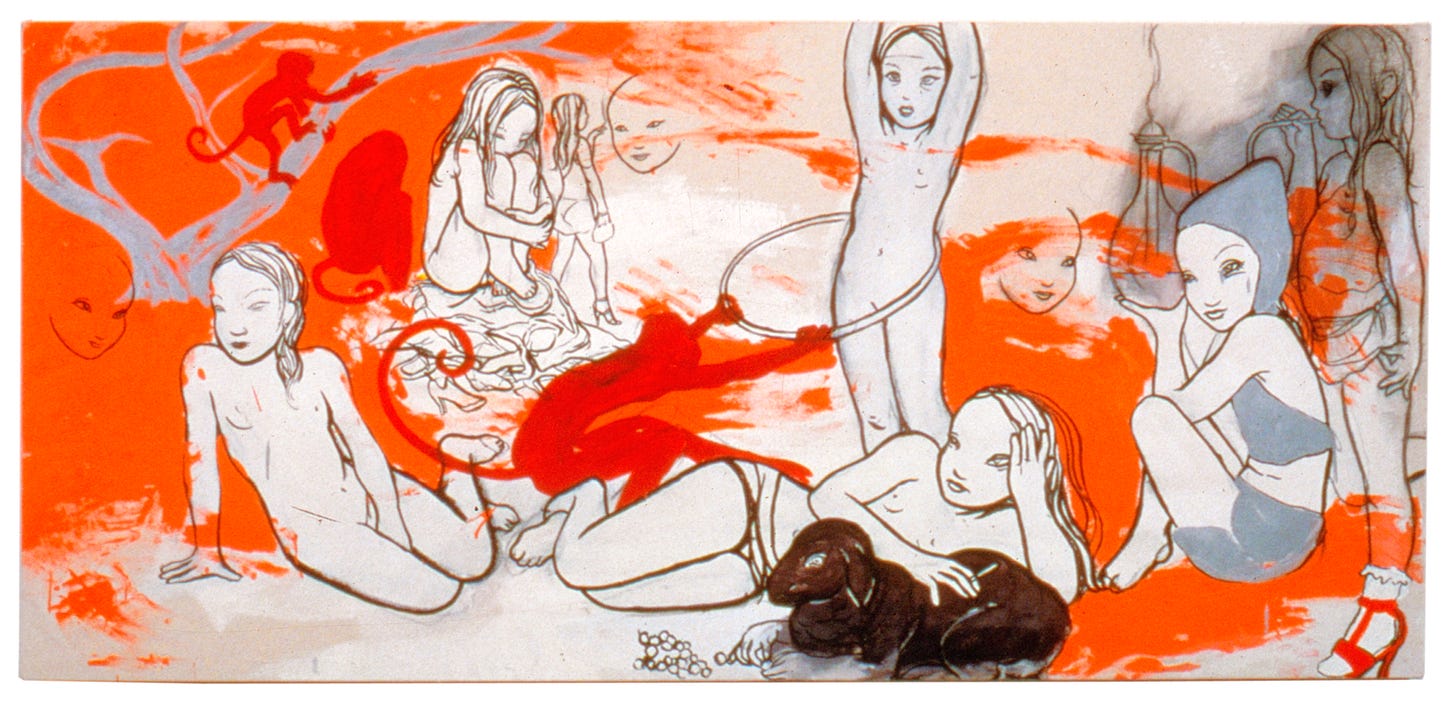

A Hungarian émigré, Ackermann surfaced in the mid ’90s in New York. Her work seemed provocative, in part for its illustrational deskilling. The paintings’ eyeball-grabbing aspect had much more to do with what they depicted, however: Ackermann’s cartoony early works showed figures somewhere between girl- and womanhood who variously lounged and presented themselves to the viewer’s gaze, or went about quotidian tasks like laundry and dishes. They were often shirtless, which gave them a disturbing Darger-esque quality. But in Ackermann’s hands, this line of approach had a legitimating connection to the era’s “bad girl” feminism (apologies to Marcia Tucker). With plenty of other, stranger or more cerebral painters kicking around—Nicole Eisenmann and Karen Kilimnik come to mind—I was never a big fan. But her work had a quiet aggression that I could appreciate.

At the same time, a lot of Ackermann’s appeal was, and remains, that she and her work are fashionable. This vibe-based metric is hard to prove, but let’s compare her press clippings to those of her current Hauser and Wirth stablemate, the aforementioned Eisenmann. (For some reason, H&W begins Eisenmann’s selected press in the year 2000, but her CV at Anton Kern goes all the way back.) In the years 1994–2001, Ackermann appears in fashion and pop culture magazines 13 times, in outlets including Paper, Dazed and Confused, and Self-Service. On Eisenmann’s CV over the same period, the closest thing you get to a fashion rag is . . . Elle? If you want a more precise sense of Ackermann’s milieu, in the years between 1994 and 2017, she appeared in proto/Euro indie-sleaze merchant Olivier Zahm’s various Purple outlets 19 times—at most magazines, enough to make you a contributing editor.

By all accounts Ackermann is a nice person and cool character, but as we all know—do we?—neither that nor a strong connection to the image-making industries par excellence makes one’s art good. The Times ran a profile in 2012 that, while hatchety, traces her long-term appeal to the worlds of fashion and nightlife even as the artist asserted she was done with it: “I don’t need that kind of attention anymore. . . . I don’t feel that it takes my work anywhere. Fashion is not the world I’m striving for.” As for the truth of that, cut to Chloé fall/winter 2020.

I’m all for securing the bag (pun intended), looking good, and having a good night out on the town. But let’s separate that from the art itself. Here I’ll use what I’ll call the Roberta Index. The level-headed, recently retired Smith positively reviewed Ackermann’s work in 1996 while also calling it “stultified by the conventions she seeks to recycle”; twenty years later, she described it as “quite tasteful” but “not original.” Today, nearly another decade on, the same declarations could apply. At some point in the early teens, Ackermann clearly spent some time working on her abstract chops, such that by 2017, her work had become blandly accomplished enough to become décor at Eleven Madison Park.

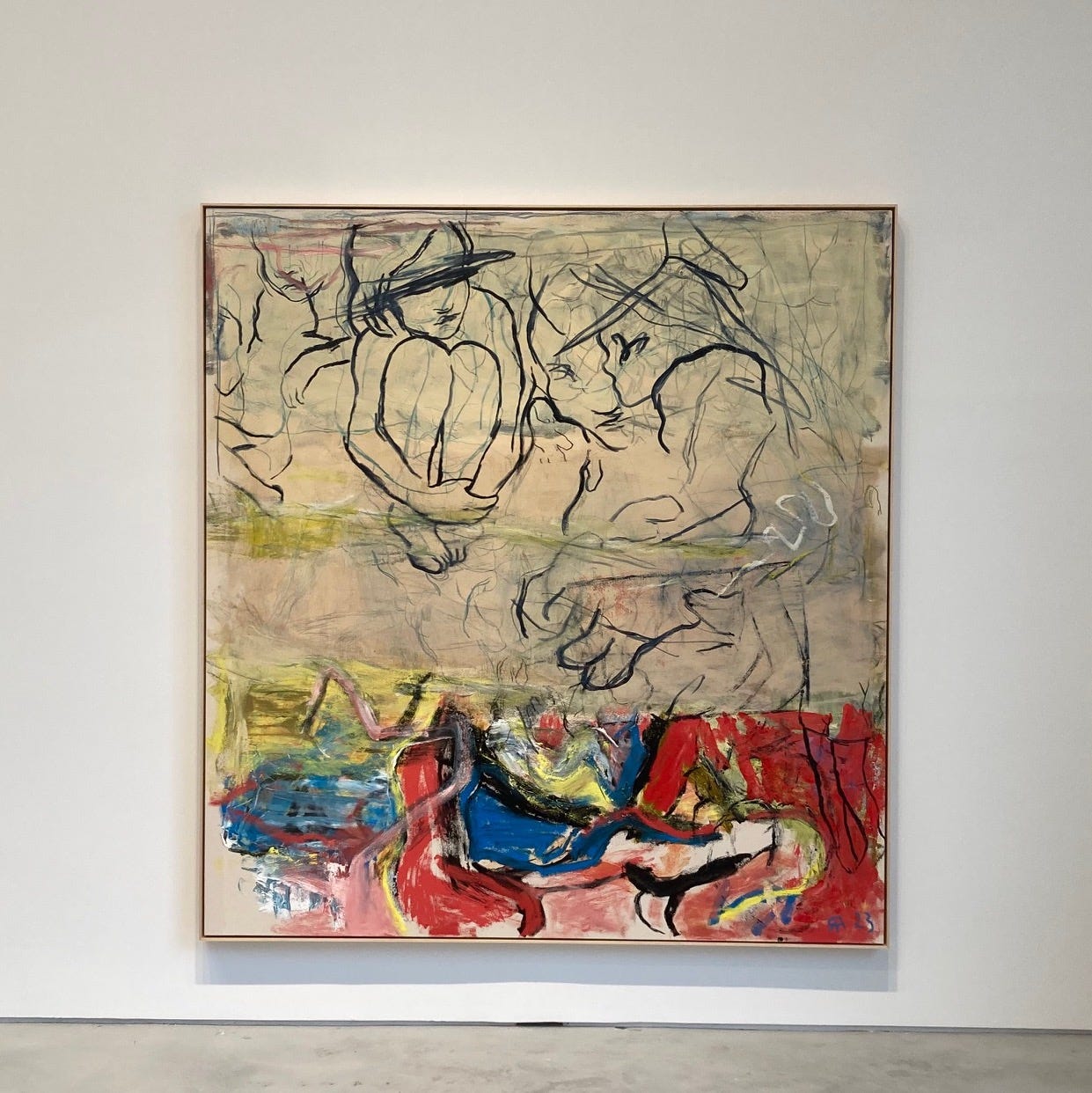

Ackermann’s midcareer claim to seriousness rests on tactics of effacing and overpainting. In the current exhibition, titled Splits, evolved versions of her signature outlined jeune filles are interrupted with patchy paint in nondescript colors—bright yellow, basic orange, boy/girl pink and blue. The combination of scribbly figuration with de Kooning riffs is perfect for making the collector feel like they’re getting their money’s worth, something that’s recognizably “art” but also a little novel. Her new works, divided into horizontal thirds, literalize this dichotomizing strategy—the show called Splits, after all.

The new paintings are typified by Mouchette’s Manners (2023), presumably named after Bresson’s film; perhaps the young woman depicted clutching her knees is meant to be its immiserated protagonist. The gap between Bresson’s exacting, antitheatrical practice and Ackermann’s, which relies on caricatures of both girl/womanhood and abstract painting, could not be much greater. The bottom third erupts into patches of pastel primaries, flatly applied. For an educative contrast, visit the show currently up at Gladstone by Amy Sillman, who doesn’t need to lay it on thick to create dynamic motion, rhythm, and optical effects.

At times, Ackermann covers the eyes of her vulnerable figures with black bars. Shame? A protective mechanism for victims of trauma? These bars do add an emotional layer to the work, effectively emphasizing the humanity bound up in the representations by interrupting them. The eruptions of AbEx arguably could be doing much the same in a beaux-arts register, against the figurative “expression,” but in context that juxtaposition feels a little hollow.

When I was leaving the gallery, I ran into a younger associate who missed Ackermann on the first go-round, who described her work as giving mid-2000s Warped Tour. Because I’m a fossil, I’ve been trying to parse this ever since. The best way I can correlate it with my own experience at Splits is that the paintings are like abstraction the way My Chemical Romance is like a punk band: the image of the thing, precisely what you expect to see on a big stage.